Housing Inequality Is So Entrenched It Could Spark a Movement Scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor says establishing a human right to shelter may seem utopian but is long overdue

By Mary Braswell

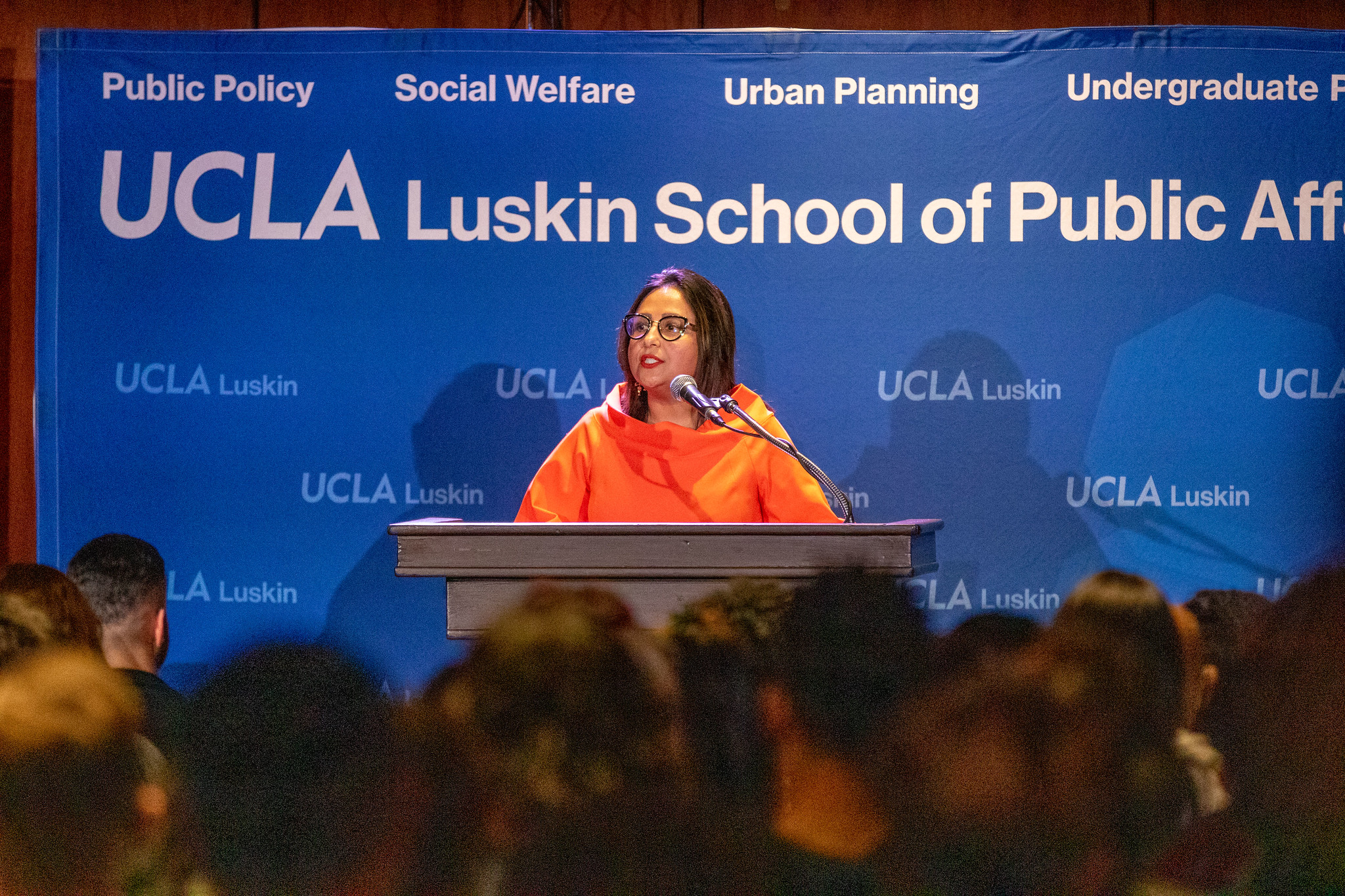

At the outset of her appearance before a UCLA audience, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor made one thing clear: The United States is not in the midst of a housing crisis.

“ ‘Crises’ are interruptions in the status quo, and housing precarity is a permanent feature of U.S. society,” said Taylor, a leading scholar of social movements and racial justice.

It was a semantic distinction that pointed to a formidable challenge: What can be done to dismantle a housing system that Taylor said has been hijacked by corporate interests, turning the family home into a hedge-fund commodity traded on the international stage?

“What we’re seeing is the deep marginalization of the socially useful purpose of housing as a dwelling … turned into an asset to be bought and sold, an asset that is mostly valued as a thing, not as a place to live,” Taylor said.

But she assured the audience that the arc of history that led to this harsh 21st-century reality also holds lessons on how to establish a human right to decent shelter.

Taylor shared insights from her 2019 book “Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership,” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. The professor of African American Studies at Northwestern University has also received accolades that include a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation.

Her newest enterprise, as co-founder of Hammer & Hope, a magazine exploring Black politics and culture, launched just hours before her standing-room-only appearance on Feb. 15 as part of the UCLA Luskin Lecture Series, in partnership with the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy.

Taylor warned against oversimplifying the solution to housing insecurity. Raising wages just to make sure people can afford exorbitant mortgages and rents, for example, only perpetuates a corrupt system.

While the racial wealth gap is real, she said, “it is often used as a smokescreen to blot out the larger dimensions of extraordinary housing inequality and insecurity.”

Today’s housing system takes a toll not just on the Black community, which has endured generations of racist policies in the real estate industry, and not just on the nation’s poorest, those living outdoors or struggling to pay rent for substandard shelter.

“We’re talking about half of the United States living with rent burden, paying 30% of their income toward rent, and more than a quarter paying half of their income toward rent,” Taylor said. “This housing economy is like roller skates with no stops on a steep hill on the top of a mountain. … There are no brakes on any of this, and every year, it’s getting worse and worse and worse.

“And so I think it becomes the basis upon which to build a different kind of a movement.”

Taylor recalled pivot points in U.S. history when tenants rose up to demand change and governments enacted tough regulations to curb “the worst impulses of capitalism.”

She spoke about the promise of current efforts, including the Green New Deal for Public Housing and alternative solutions such as co-ops and community land trusts.

“Such proposals might have once seemed utterly utopian,” she said. “They now feel long overdue.”

Following her lecture, Taylor shared the stage with scholars Cheryl I. Harris of UCLA Law, Marques Vestal of UCLA Luskin Urban Planning and Ananya Roy, founding director of the Institute on Inequality and Democracy. The dialogue continued the following day when Taylor met with grassroots organizers at the Los Angeles Community Action Network in downtown’s Skid Row.

“We see an economic system that is incompatible with housing security and housing justice,” Taylor said at the lecture. “And so that raises another question about what kind of world we want to live in and the struggle that is necessary to produce it.”

View photos from the lecture on Flickr.

Watch a recording of the lecture on Vimeo.