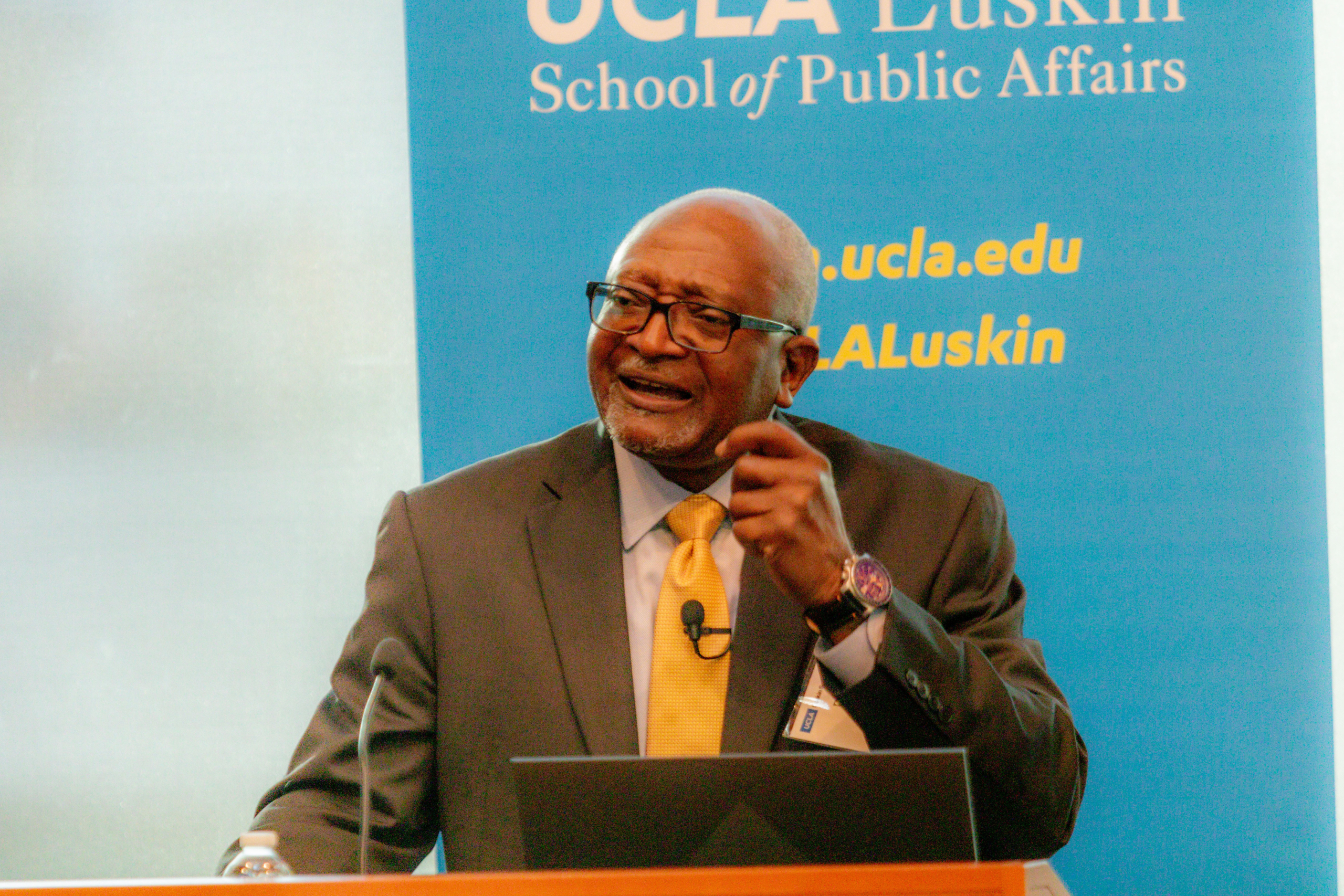

Joe Nunn, at the Heart of Social Work Education UCLA Luskin professor emeritus reflects on what has changed during his six decades in the profession and its teaching — and what’s still in progress

By Stan Paul

Social work education is going through a transition based around social justice, said Joe Nunn, emeritus professor of social welfare, but change is nothing new for the profession or for UCLA.

Nunn has a long affiliation with the university, first coming to the Westwood campus as a 17-year-old freshman in winter of 1961, then continuing through pursuit of his MSW and doctorate degrees, and later to the faculty. He retired in 2006.

Recalling his time as an MSW student from 1968 to 1970, he said, “One of the major transitions — and it’s still always going to be an issue — I think was diversity.”

Recalling his time as an MSW student from 1968 to 1970, he said, “One of the major transitions — and it’s still always going to be an issue — I think was diversity.”

During a time of anti-war and anti-discrimination marches and protests, UCLA Social Welfare had just two instructors who were African American. He and other students demanded that a tenured Black professor be added.

Douglas Glasgow, an assistant professor, was the only tenure track instructor at the time. Subsequently, Glasgow was promoted to associate professor and also served as director of the Center for Afro-American Studies (now the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies). Glasgow went on to become dean of Howard University’s School of Social Work.

“We’ve since had more African American faculty members than we had early on,” said Nunn, pointing out that the field faculty has been, in general, more diverse than the faculty as a whole across programs locally and nationally. But “there’s still more to be done.”

Before becoming director of field education from 1991 to 2006, Nunn’s first job after earning his undergraduate degree was working with juvenile offenders in the probation department for Los Angeles County in the mid-1960s. His work schedule spanned early mornings, afternoons and late nights, sometimes into the wee hours.

“When you’re with kids, you’re there all day. I mean, you’re 100% time with the unit,” he recalled.

It was during this time that he became aware of the work being done by social workers with youth and their families, he said. “I got to work with some of them. That’s what really connected me to social welfare and the profession.”

‘Social work, as a community, should be community-connected because it is a service, that link between town and gown, so to speak, between the university and the community.”

He continued as a probation officer in Los Angeles after earning his MSW, totaling 15 years in all. He began working with interns from UCLA who were associated with the county’s probation camp.

“That was the first time I think they had social welfare interns. I was studying for the LSAT when my field liaison, Trudy Saxton, encouraged me to consider a doctorate in social work,” he said. “So, that’s what got me out of probation and into the PhD program.”

As a doctoral student, Nunn focused on juvenile justice.

“I looked at the attitudes of social work professionals and lay people from the Black community toward youth in trouble … how they viewed these kids in terms of what they thought should be the outcomes of providing service to them.”

His next career move was becoming assistant dean for field education at USC.

“That was hard to go across town, being such a Bruin, but I thought it was an opportunity. So, I went there for four years. And I learned a lot because I’d never worked for a private entity before.”

After returning to UCLA to direct its field education program, Nunn taught courses on cross-cultural awareness and social work. He played an integral role in developing the first course on juvenile justice for UCLA Social Welfare.

“Had to really fight for that,” Nunn said, because juvenile justice wasn’t a significant focus at the time. That has changed in recent years, as exemplified by current Social Welfare chair Laura Abrams, a professor whose focus is on juvenile justice.

The field training aspect has been a constant for Nunn, who has served in leadership positions for the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE), which sets national standards for social work education. He recalled being at an annual meeting with thousands of social work educators representing hundreds of social work programs. Nunn and a few colleagues noticed something was missing in the conference’s attendees and recognition programs.

“The people missing were the field instructors, the people who actually work with our students in the community,” Nunn said. So, he worked with peers at Cal State Long Beach to start the Heart of Social Work Award, an award that is now given at the organization’s annual conference to outstanding field instructors across the country. The award prompted more universities to sponsor field instructors to come to the conference and receive the award.

Over his career, Nunn has been awarded regional and national honors such as the National Association of Social Work, California Chapter Social Worker of the Year. Since 2007, he’s been the namesake for UCLA Luskin’s Joseph A. Nunn Social Welfare Alumni of the Year.

One honoree was Aurea Montes-Rodriguez MSW ’99, now executive vice president of the Community Coalition in Los Angeles, who spoke about Nunn at the award celebration in 2017. “I am surprised and very humbled to be nominated and selected, especially for an award named after Dr. Nunn,” she said. “When I was a student, I looked up to him and admired the work he had done around juvenile criminal justice — thinking about ways we could do a better job eliminating the cradle-to-prison pipeline so we can develop a healthier generation.”

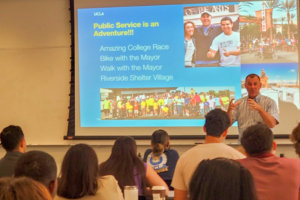

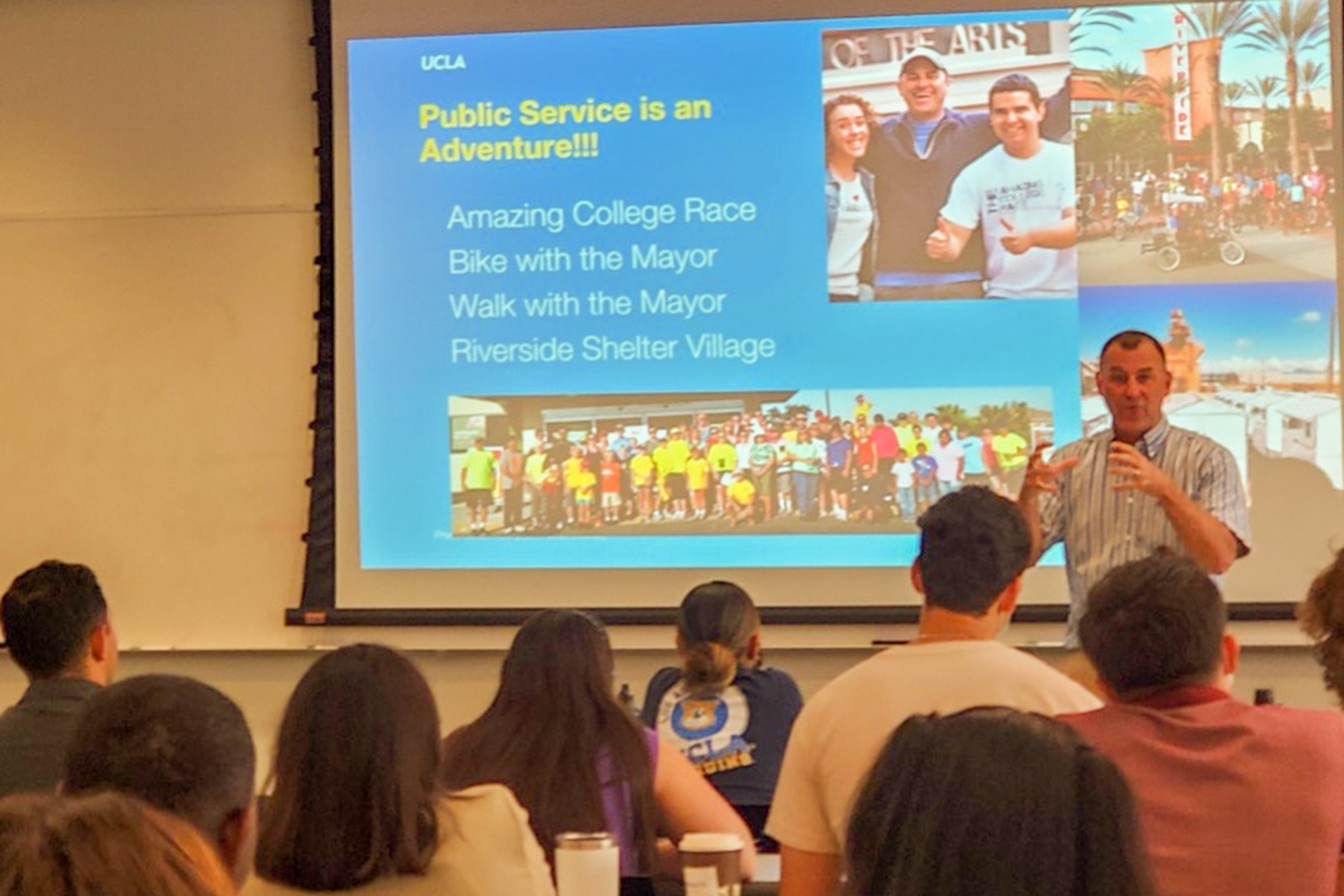

For decades, Joe Nunn has been an observer, an instigator of change and a teacher in a profession that, at its heart, continues to advance one overriding mission — public service.

“Social work, as a community, should be community-connected because it is a service,” Nunn said, “that link between town and gown, so to speak, between the university and the community.”

“It was January. I was writing a paper — my constant preoccupation,” Rothman said. “I hear a voice, ‘This is Dean Leonard Schneiderman, you know, school of social work at UCLA. Would you be willing to come out for an interview visit?’”

“It was January. I was writing a paper — my constant preoccupation,” Rothman said. “I hear a voice, ‘This is Dean Leonard Schneiderman, you know, school of social work at UCLA. Would you be willing to come out for an interview visit?’”