Dispensing Knowledge in Real Time UCLA Luskin Social Welfare students present the results of their rapid response research projects

By Stan Paul

Research, by design, is focused, systematic, methodical. It takes time.

But when information moves at the speed of social media, and false, distracting and potentially harmful information can be spread worldwide via tapping a screen in the middle of the night, there is a pressing need for responsible research that can be produced in real time.

A dozen social welfare graduate students at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs reacted to this challenge by taking on projects — above and beyond their required studies — to match their data-gathering and synthesizing skills with the ability to make useful information available quickly to communities that may need it.

The social welfare master’s and doctoral students researched topics such as hate speech and immigration.

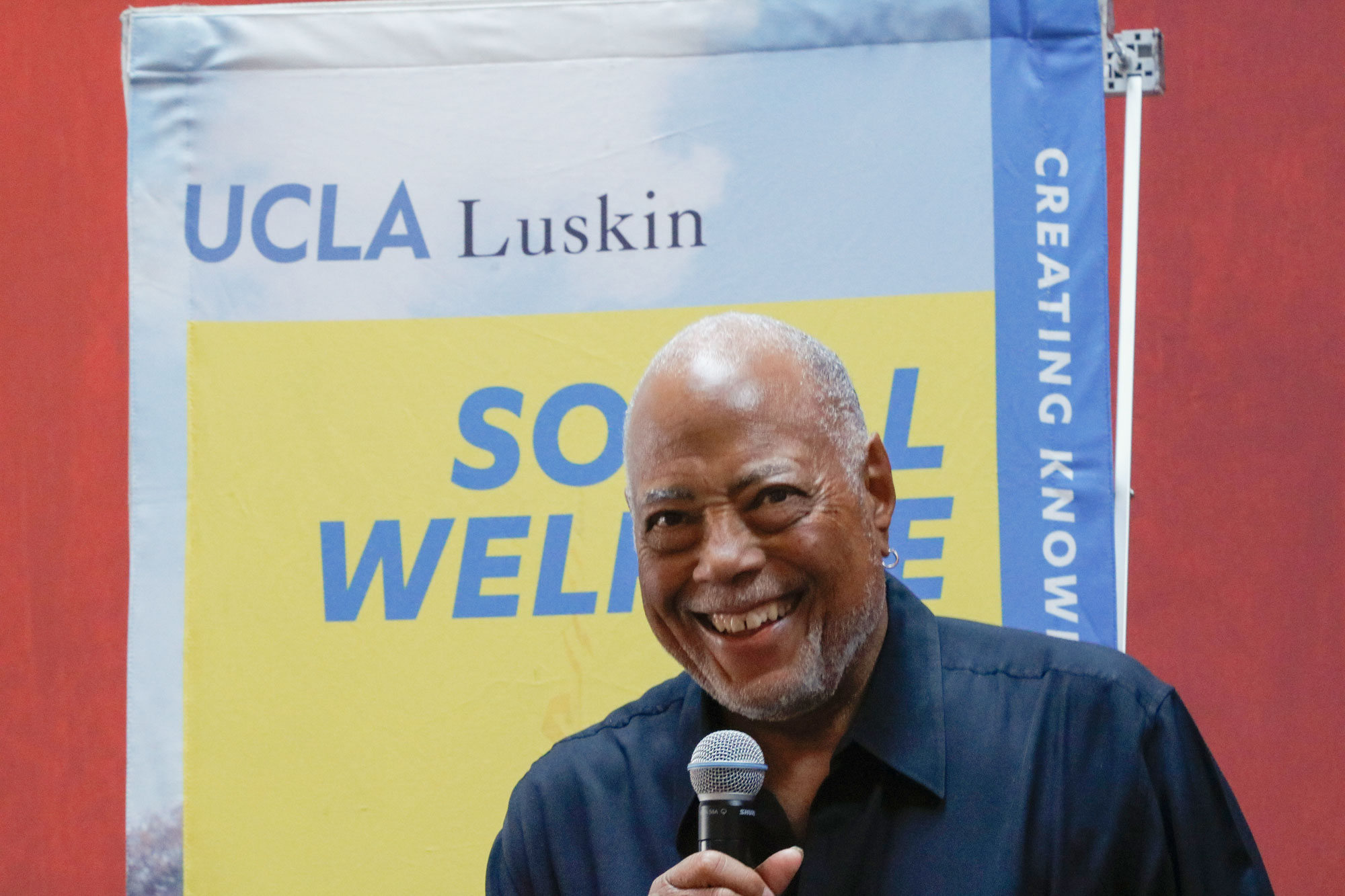

“You are going to enter your profession, a profession built around the question of human caring, at a time where human caring is not held in particularly high esteem,” UCLA Luskin Dean Gary Segura said in introducing “Rapid Response Research in the Trump Era,” a June 1, 2017, gathering at the Luskin School to review student projects.

Segura, whose research has centered on representation and empowerment, said: “You know the challenges that all of us face … across all racial and ethnic, socioeconomic subpopulations in the United States: access to affordable health care, dealing realistically and honestly with challenges that individuals and families face, providing quality education and job opportunities for people. The list is unbelievably long.

“The first piece of advice I’m going to give you for resistance is to call things by their name,” Segura said. “We must begin our resistance by calling things what they are: Racism is racism, sexism is sexism, anti-Semitism and Islamophobia are what they are.” He urged students not to pass these things off as merely rants not worthy of comment or notice.

Laura Abrams, the incoming chair of UCLA Luskin Social Welfare, said that a list of potential research ideas was presented to social welfare students early in the academic year, and a number of groups responded. The criteria for the projects included working with real-time data from social media platforms such as Twitter.

Abrams said the research topics “were going to be more immediately applicable to what communities might need in order to resist and they had to be social justice oriented.” Social welfare faculty such as assistant professors Ian Holloway and Laura Wray-Lake served as advisers for the students.

One project examined Twitter data based on the motivations of those who participated in the Women’s March, and how that motivation connects — or doesn’t — with broader issues of racial justice.

One immigration issue tackled by the students was part of a nationwide project asking how young people have been affected by the policies and rhetoric of the Trump administration. That project relied on responses from Latino high school students. The information gathered is intended to inform educators and others working with adolescents.

First-year MSW student Alexandra Rhodes said she studied anti-LGBT hate speech and the incidence of particular words used on Twitter.

“I was interested in seeing if anti-LGBT hate speech on Twitter increased after Donald Trump’s election,” said Rhodes, who gathered information from more than 40,000 users who had tweeted anti-LGBT search terms. From that group, just over 10,000 users were randomly selected for comparison of the number of such tweets before and after the election.

“I was most interested in how Donald Trump’s election was affecting the LGBT population given his seemingly anti-LGBT rhetoric and policies,” said Rhodes, who is primarily interested in working with the LGBT population and is considering pursing a Ph.D. in social welfare.

“It is very important to me to do ethical and essential research in my community and build evidence to support how we have been affected by various social changes and policies,” Rhodes said. “For now, I’m focusing on getting involved with research in whatever way I can as an MSW student. It is important to do research and look at the data and respond to what is happening right now.”

Abrams said she hopes that this becomes a tradition that can continue to be built into the curriculum in a meaningful way.

“As a Social Welfare Department, the rapid response research projects are a prime example of what we can accomplish when we have an idea, put our heads together, and work hard as team,” Abrams said. “I am proud of the students for carrying out their projects in such a timely and rigorous manner.”