A UCLA study published today shows that hot weather significantly increases the risk of accidents and injuries on the job, regardless of whether the work takes place in an indoor or outdoor setting.

The report is based on data from California’s workers’ compensation system, the nation’s largest.

“The incidence of heat illnesses like heat exhaustion and heat stroke definitely go up on hotter days,” said the study’s lead researcher R. Jisung Park, an assistant professor of public policy at UCLA Luskin. “But what we found is that ostensibly unrelated incidents — like falling off a ladder or being hit by a moving truck or getting your hand caught in a machine — tend to occur more frequently on hotter days, too.”

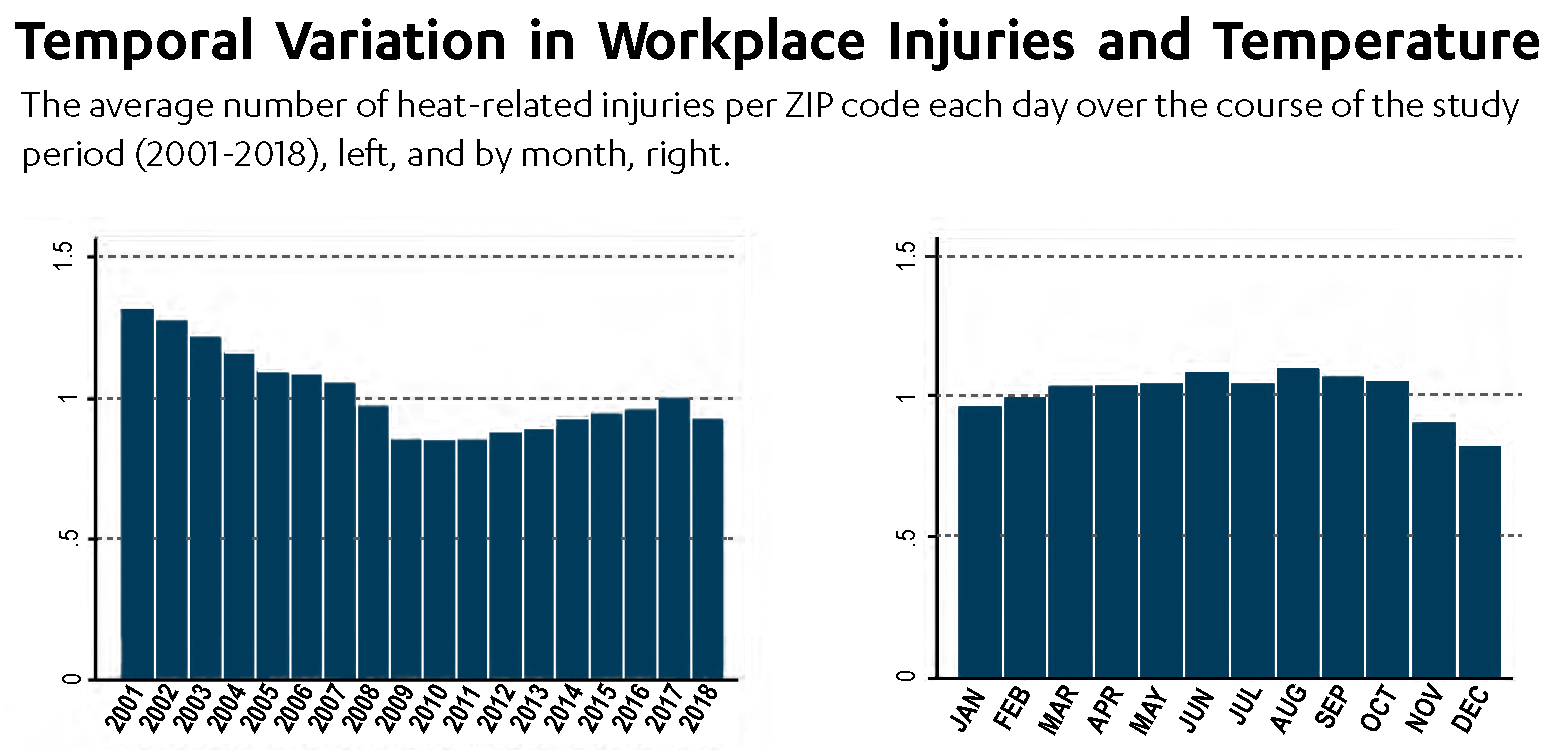

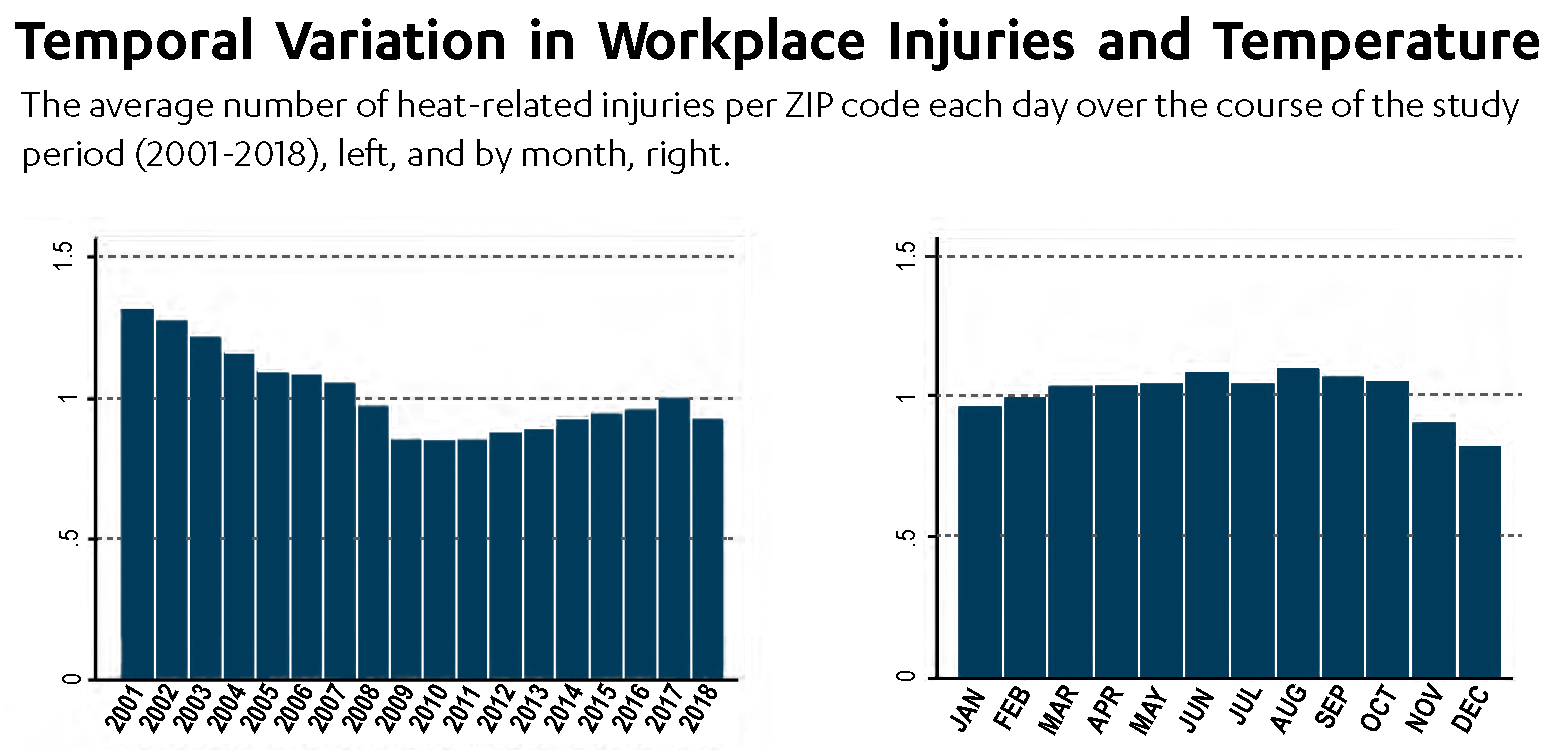

By comparing records from more than 11 million California workers’ compensation claims from 2001 to 2018 to high-frequency local weather data, Park and his co-authors isolated the impact of hotter days on the number of injury claims.

The study shows that on days with high temperature above 90 degrees Fahrenheit, workers have a 6% to 9% higher risk of injuries than they do on days with high temperatures in the 50s or 60s. When the thermometer tops 100, the risk of injuries increases by 10% to 15%.

Those findings are particularly alarming in the context of climate change, which is expected to produce more high-temperature days each year. The researchers estimate that high temperatures already cause about 15,000 injuries per year in California.

“Heat is sometimes described as a silent killer,” said Nora Pankratz, a UCLA postdoctoral scholar. “But if you look into the data and do the statistical analysis, you find that heat has a significant impact on mortality and health outcomes.”

It’s not surprising that hot weather would lead to injuries and illness among workers in predominantly outdoor industries such as agriculture, utilities and construction. But the data consistently show that industries in which most people work indoors are affected as well. In manufacturing, for example, days with high temperatures above 95 degrees have an injury risk that is approximately 7% higher than days with high temperatures in the low 60s.

“A lot of manufacturing facilities are not air conditioned,” said Stanford University postdoctoral scholar A. Patrick Behrer, the study’s other co-author. “Because you’re inside, you don’t necessarily think about the temperature as being a major threat.”

The reality is that overheated workers face numerous risks, regardless of where the work occurs.

“Heat affects your physiology,” Park said. “It affects your cognition. It affects your body’s ability to cope. It seems possible that what we’re observing in the data for these workers is that they’re more likely to make mistakes or errors in judgment.”

The researchers found that heat-related workplace injuries are more likely to be suffered by men and lower-income workers. In addition, younger people suffer more heat-related injuries, possibly in part because they’re more likely to hold jobs with greater physical risks on construction sites, in manufacturing plants or at warehouses.

For an office worker at a computer desk, nodding off on a hot summer afternoon is unlikely to cause an injury. “But if you have a huge chainsaw in your hand, you’re not in a great situation,” Park said.

Among the paper’s other conclusions:

- The number of heat-related injuries actually declined after 2005, when California became the first state to implement mandatory heat illness prevention measures for outdoor workplaces on days when temperatures exceed 95 degrees.

- The financial costs of heat-related injuries may be between $750 million and $1.25 billion per year in California alone, considering health care expenditures, lost wages and productivity, and disability claims.

- Inequalities in the labor market are exacerbated in part by the fact that low-income communities tend to be situated in hotter parts of the state. People in the state’s lowest household income tier are approximately five times more likely to be affected by heat-related illness or injury on the job than those in the top income tier, the study found.

The UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation, where Park is associate director of economic research, provided funding for the study. It is available now through the Institute of Labor Economics, which disseminates working versions of potentially influential research prior to publication in academic journals. Park previewed the findings July 15 during testimony at a Congressional hearing organized by the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis.

The new study echoes the results of a 2019 study that focused on how extreme temperatures raise injury risk in Texas and in the U.S. mining industry. Park, whose prior research includes a finding that student learning is negatively impacted by warm temperatures, said there has been “an explosion of research just in the last five to 10 years that illustrates, using data, the serious consequences of climate change for health, productivity and economic growth. This likely adds to that urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions now.”

Pankratz got involved in the study while working at UCLA Luskin as a postdoctoral scholar, having previously researched the impact of heat on businesses while working toward her Ph.D. in the Netherlands.

Worldwide, she said, there is growing interest in the concept of adaptation — the pragmatic changes that can be made by governments and businesses to cope with the reality of climate change.

“For a long time, the focus has been on mitigation — what can we do to prevent climate change,” she said. “But as it becomes more and more obvious that there is policy inertia on mitigation, it’s important to think about what we can do to adapt and to work as well as possible in a warmer world.”

The study authors, all of whom have backgrounds in economics, realize that the desire to protect workers from heat may be complicated by economic reality.

Behrer said policymakers could stipulate that workers not be exposed to the heat on days above 100 degrees, for example, without proscribing a specific strategy to be used by individual business owners.

“Then firms have the option either to use air conditioning or come up with some other method of climate control for their facilities,” he said, noting that some might change work hours or shorten the work day during heat waves. “It allows them to decide the most cost-effective way for them to meet the objective of reducing workplace injuries.”