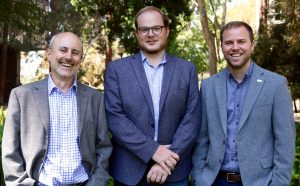

By George Foulsham

From left, Michael Ross, professor of political science; Graeme Blair, assistant professor of political science; and Darin Christensen, assistant professor of public policy at UCLA Luskin, are the co-founders of PRDG. Photo by George Foulsham

For three UCLA scholars, it just didn’t add up. Why do so many people who live in developing countries with an abundance of natural resources struggle in poverty every day?

“You would think that it’s a simple thing to take wealth that’s underneath the ground and turn it into wealth on top of the ground for everybody to share,” said Michael Ross, a professor of political science at UCLA. “But we know from studying countries around the world that that very rarely happens.”

Social scientists call it the resource curse, and it’s one of the reasons why Ross and two UCLA colleagues, UCLA Luskin’s Darin Christensen and political science faculty member Graeme Blair, have created the Project on Resources, Development, and Governance (PRDG), a network of social scientists, policymakers, nongovernmental organizations and industry representatives dedicated to finding policies that promote welfare, peace and accountability in resource-rich countries.

“For the past 15 years or so, I have been living in two worlds,” Ross said. “One is an academic world where I do research and I speak to some of the smartest young social scientists in the world who are studying the problems of developing countries. In the other world, I’m sitting around the table with policymakers who are worried about how to fix a problem called the resource curse.”

About three dozen countries in the low- and middle-income world are economically dependent on oil, gas and mining, but they all seem to struggle despite the riches provided by the resources. Those countries include Angola, Kenya, Uganda, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia, Indonesia, East Timor and Kazakhstan.

“They tend to be conflict-ridden,” Ross said. “There are protests, there’s pollution, there are civil wars around these projects.” There’s also plenty of corruption, with many of the countries in economic turmoil because of bribery and other issues in regions of exceptional resource wealth, such as mining areas.

“There are so many opportunities for corruption, and politicians are a whole lot less responsive to the people and a whole lot more concerned with siphoning off money for their own bank accounts overseas,” Ross said.

Finding solutions to these challenging issues won’t be easy.

“We have a generation of super-smart young political scientists and economists who are interested in this problem,” Ross said. “Our project is designed to bring together the smartest sort of leading-edge people in political science and economics with the policymakers who are dealing with these problems on a day-to-day level.”

That mission officially begins Sept. 21-22, 2017, with the first PRDG summit at the Luskin Conference Center on the UCLA campus. Researchers and policymakers from UCLA, the World Bank, Barnard College, the University of Pittsburgh, the Natural Resource Governance Institute and many other organizations and universities will make presentations and discuss issues that range from creating successful research-policy partnerships to the research priorities of funders.

The September conference at UCLA was generously funded by the Luskin Center for Innovation, Natural Resource Governance Institute, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Burkle Center and UCLA’s Political Science Department. The initiative also recently received a one-year, $600,000 grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation to support additional workshops in Washington, D.C., and Accra, Ghana, and the research partnerships that emerge from these meetings.

“One of the important parts of PRDG is the effort to bring in local researchers,” said Blair, assistant professor of political science at UCLA. “We want to provide training in modern social science research methods, and to provide learning-while-doing at matchmaking workshops where we bring together academics, policymakers and practitioners.”

Providing guidance on policy issues is Christensen, assistant professor of public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. “I think policy plays an essential role in this PRDG initiative,” Christensen said. “What PRDG is trying to do is bring policymakers and academics around the same table and allow policymakers to propose solutions and team up with researchers who can go to the field and determine whether these new initiatives are actually helping root out the corruption or address the grievances that often accompany these big mining, oil and gas projects.”

PRDG’s short-term goals include generating a series of new research projects on solutions to problems faced in resource-rich countries, bringing together researchers, policymakers and practitioners. “Another goal is to start joint learning exercises where we go out into the field and try to help build research into their existing program,” Blair said.

In the long term, the UCLA researchers are hoping that the conversation about these issues becomes circular — the research feeds back into the policymaking conversation, which generates new questions the researchers can tackle.

“We want to figure out ways to make a difference, and find ways to fix this problem,” Ross said.