Team from UCLA Luskin Social Welfare counsels mothers and children seeking asylum in the United States

DILLEY, Texas — Angela “Angie” Garcia was 1,500 miles from home, and she had just finished a 12-hour shift as a volunteer providing assistance to refugee mothers and children at the largest immigrant detention center in the United States.

Seated in a circle for a nightly recap known as “big table,” she and other volunteers seemed frayed but composed — almost stoic. Garcia was there as part of a team of four students and two faculty from UCLA Luskin Social Welfare. They and volunteers from other universities and legal services had spent the day listening to gut-wrenching stories told by women and children being held in the South Texas Family Residential Center.

Garcia thought of her own parents’ migration from Mexico. And when it was her turn to share, tears began to flow. Garcia’s expression of heartbreak granted others permission to do the same, and soon emotions flowed freely.

“This trip has changed the way I see my own family’s journey,” Garcia explained later. “I texted my parents at the end of the first day. … ‘Thank you. Thank you.’”

The small town of Dilley, Texas, and the immigrant detention center there became a focal point of the immigration debate in 2018.

NEXUS OF U.S. IMMIGRATION DEBATE

Dilley, Texas, is only 84 miles from the Mexico border. It may not be ground zero for the nation’s polarizing conflict over immigration, but it’s close. For one week this year, it became a real-life, transformative classroom for Garcia and two other second-year MSW students at UCLA Luskin, Fatima Gonzalez and Marianna Hernandez, plus first-year MSW student Anthony Gómez. They and faculty volunteers Ayako Miyashita Ochoa and Sergio Serna cited their families’ immigrant backgrounds as motivation for volunteering.

The detention center was built during the Barack Obama administration to house migrant families seeking asylum in the U.S. But it wasn’t until President Donald Trump’s administration began separating immigrant children from their mothers that the center gained notoriety.

“When I first started with the project, we would struggle to have five, 10 volunteers,” said Cindy Woods, one of two staff attorneys working with the Dilley Pro Bono Project. “After family separation, there was a lot more attention to this issue. So now we are maxed out on volunteers.”

The February trip to Dilley was proposed to Serna in the summer of 2018. Soon after, Laura Abrams, chair of UCLA Luskin Social Welfare, connected with the dean of the School of Social Work at the University of Washington, Eddie Uehara. At UW, the School of Law also became involved, and discussions produced a partnership and a vow to send representatives from both universities to Texas for a week of volunteer service.

The Dilley Pro Bono Project represents detained mothers and children who are fleeing extreme violence in Central America and elsewhere.

THE DILLEY PRO BONO PROJECT

The Dilley Pro Bono Project is part of the national Immigration Justice Campaign, a joint initiative of the American Immigration Council and the American Immigration Lawyers Association. According to the Immigration Justice Campaign website, the project provides legal services at no cost to detained mothers and children — at any given time there might be 2,400 in custody — who are fleeing extreme violence in Central America and elsewhere, and are seeking asylum in the United States.

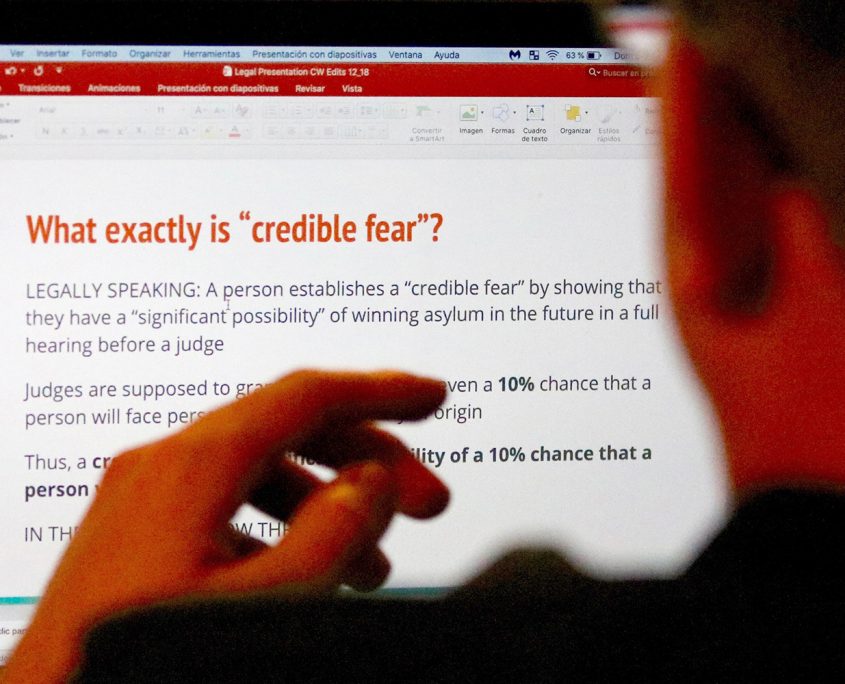

The detainees interviewed by the UCLA volunteers were mothers with children under 18 who had recently crossed the border into the U.S. The majority of the immigrants were from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. The project staff say that more than 99.5 percent of detainees who go through what are known as “credible fear interviews” and an appeals process are eventually released from detention to await further action on their plea for asylum.

Katy Murdza, advocacy coordinator, said volunteers are vital to the project’s success because only 12 permanent employees are on staff.

“Families have a right to and need advice on how to go through their credible fear interview,” Murdza explained. “Getting a positive on their interview is the key to being released from this detention center. Volunteers, while they might not have experience and it’s a lot to learn very quickly, can make a huge difference.”

The team from UCLA Luskin Social Welfare included four students and two faculty members.

THE UCLA TEAM

The UCLA Luskin team was made up of current and aspiring social workers, and their assignment at Dilley was strictly defined as legal counselors for the families seeking asylum. A refugee’s ability to show credible fear is usually key, and learning what qualifies is part of the educational process for volunteers. The UCLA volunteers’ backgrounds in social work served them well.

The bridge from law to social work is a short one for Serna, a field education faculty member at UCLA Luskin. “This is where the legal expertise can easily be paired with the social work expertise. It’s more than just legal issues being identified in this situation. Families aren’t just dealing with needing representation to get released from detention. They’re dealing with emotional issues. They’re dealing with trauma. I think, at that particular nexus, social work takes over.”

Miyashita Ochoa, an adjunct faculty member with UCLA Luskin who has also taught at UCLA School of Law, has legal experience working with immigrants living with HIV in Los Angeles. “I often say that I can teach a social work student the law, but oftentimes I can’t teach a law student social work,” she said.

The UCLA Luskin volunteers walked across a field to the banks of the Rio Grande to peer across the river at the Nuevo Laredo port of entry in Mexico.

A TRIP TO THE BORDER

The UCLA Luskin volunteers began their week in Texas with a trip to Laredo and the U.S.-Mexico border. The group walked across a field to the banks of the Rio Grande, peering across the river at the Nuevo Laredo port of entry.

“It was important to explore, to see what it looked like,” Serna said of the border trip. “I didn’t realize how important it was until we actually got there. We were able to go right on the edge of the Rio Grande, which was unexpected — especially right now with this narrative and this rhetoric about the Wall.

“The students walked right up to the edge, looking down into the river, looking across,” he added. “They were able to see people fishing on the other side, people playing soccer, leading normal lives — almost like a mirror of what our experiences are like here in the United States. I think they were surprised by how peaceful it was. It felt very normal.”

For Garcia, the road trip was important because President Trump had declared a state of emergency at the border just a few days before the UCLA team departed California for Texas.

“And then we got to the border, and it’s just a river,” she said. “It could be that simple. We could just sit, one side to the other, and say, ‘Hello!’ But it’s not. It’s because we make this river this object — we create a barrier. And they want to create an even bigger barrier. It’s so much harder than it needs to be.”

Inside the detention center, just 15 steps separate freedom from confinement.

GOING INSIDE

After orientation and training, the UCLA team headed to the South Texas Family Residential Center. (Photographers and journalists are not allowed inside the detention center, so this part of the story is told through the eyes and experiences of the volunteers.)

Each day, the names of all volunteers are checked off a list and IDs are checked. Bags pass through screening, and bodies are scanned with an electronic wand. Just 15 steps separate freedom from confinement as volunteers make their way to the project’s workspace inside the detention center.

Watch a video in which UCLA volunteers talk about their heart-breaking interactions with refugee families

Serna and Gonzalez said their first impression was seeing “color everywhere” — a sea of fluorescent pink, red, brown, blue, purple and neon green sweatshirts and jackets supplied at the facility because the clothes were inexpensive and the mothers and children are institutionalized. “You see that and you know: These are not people that are free,” Miyashita Ochoa said.

Then came the sounds of children running, crying, playing — all speaking Spanish.

The interviews with detainees sometimes took place over a period of days, four or five hours at a time, seeking to establish credible fear qualifications so the detainees could apply for asylum. The meetings took place in private rooms, usually with the children present, and without Border Patrol or Immigration and Customs Enforcement personnel.

The volunteers struggled to reconcile themselves to a process in which the definition of success — getting a positive in the credible fear interview — required retraumatizing women and children as they recounted the brutality that led them to flee their home countries.

Each night, the volunteers spent hours compiling notes to assist asylum seekers during their final interviews with government officials. In several cases, the UCLA Luskin volunteers sat in on final hearings.

The evidence in almost every case proved that the immigrants weren’t seeking handouts or simply a better life for their families, according to the volunteers. Rather, they sought safety for themselves and their children — a chance to stay alive.

At first, Hernandez was surprised that the detainees wanted their children in the room during the interviews.

“And then I had to remind myself that these kids lived everything that was coming out of the mothers’ mouths,” she said. “It wasn’t news to them. People entered their homes with guns and threatened them, too.”

Hernandez, whose academic focus is juvenile justice, said she kept thinking, “How are all of these families going to recover from this trauma? This is going to become intergenerational trauma.”

UCLA team members said the experience changed their lives.

‘SOCIAL WORK AT ITS FINEST’

The UCLA team members said they were horrified by the stories of hardship they heard, but they were also uplifted by the courage and determination of the mothers they met. All said the experience changed their lives.

“I feel so much more invested in this issue, and so much more driven to do something about this,” Gómez said. “I am so grateful that Luskin even provided something like this. It is social work at its finest.”

Hearing the detainees’ stories was heartbreaking, but Miyashita Ochoa’s takeaway was cautiously optimistic.

“The stakes are so incredibly high,” Miyashita Ochoa said. “To be able to see mothers, mothering their children, breast-feeding their children, telling their kids not to upend trash cans in the visiting room, really just showed me how we are all the same people. We are all just trying to do the best we can with what we have. And yet, some of us, our lives are stacked against the odds.

“My mission from this point on is to focus on resiliency, to not give up. My mission is to take this experience and make it feed my fire.”

◊

This story was reported from Dilley, Texas, by George Foulsham, who also took the photographs and conducted the interviews for the video, working with videographer Michael Troxell. Some of the descriptions in the story were provided after the trip by Ayako Miyashita Ochoa and Sergio Serna of the UCLA Luskin faculty.