The Facts on School Violence: Q&A with UCLA Luskin’s Ron Avi Astor

By Elizabeth Kivowitz

Ron Avi Astor is a professor of social welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs with a joint appointment in the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. His work examines how physical, social-organizational, and cultural contexts in schools relate to different kinds of bullying and school violence. Astor and Rami Benbenishty, professor emeritus at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, have taken input from millions of students, teachers, parents, and administrators, and developed mapping and monitoring procedures that have been used to generate grassroots solutions to safety problems in schools worldwide. Over the past 20 years, findings from these studies have been published in more than 200 scholarly manuscripts.

Astor’s work has been funded by the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Mental Health, and other public and private foundations.

We caught up with Astor to gain a better understanding of school violence — and how to create safe schools.

Is school violence getting worse — and why does it happen more in the U.S.?

Overall, day-to-day school victimization, including physical, verbal and social exclusion — has declined significantly in recent decades across the United States. In contrast, behaviors involving cyberbullying through phones and the internet are on the rise. When it comes to shootings and deaths, however, the situation has worsened. The increasing frequency of shootings, intense media coverage, and widespread use of hardening measures in schools contribute to the perception that all forms of violence are escalating.

This is why it is essential to distinguish different types of victimization. School shootings are a separate phenomenon, more akin to terrorism, and should be considered independently from everyday violence. Cyberbullying is another category that requires its own focus, as it is increasing.

For day-to-day school violence, the United States is not among the most violent countries; many nations have had far higher rates for decades. But when it comes to school shootings and deaths from shootings, the U.S. is by far the highest globally and accounts for a large proportion of such fatalities worldwide.

Are there any recent lessons we are not talking about that we should be?

Yes. One major lesson is the dramatic reduction in day-to-day victimization in schools over the past two decades, a fact overshadowed by the trauma and visibility of school shootings. While shootings must be addressed urgently, these reductions mean that millions of students are no longer experiencing the same levels of victimization reported 20 years ago. This progress is often overlooked, as are the tremendous investments in programs, hiring of social workers, psychologists and counselors, and the expanded district and state safety infrastructure now in place.

Teachers, principals, and communities have made bullying and school safety a priority, and their combined efforts appear to have worked. The United States has invested billions of dollars in social-emotional learning, positive school-climate initiatives, anti-bullying programs, trained staff, and new safety policies — all likely contributors to the decline. The belief that “nothing works” to reduce school violence is incorrect, particularly for day-to-day victimization. Educators, parents, communities, and students deserve recognition. This is also why separating school shootings from less lethal forms of school violence is so important.

What is the most important thing a school can do to create a positive school climate?

After studying thousands of schools around the world, I have found that the most influential factor, across cultures, is the principal’s vision, skill, and mission. An effective principal who emphasizes both academic excellence and the social role of schools is the key to reducing violence. These exceptional leaders unify staff, students, and communities around a shared vision of safety and foster environments that are welcoming, caring, and supportive.

They integrate ideas from students, staff, and families, while also selecting evidence-based programs adapted to their school’s specific needs. One important implication is the need to include school safety content in principal and teacher training programs, as most universities currently offer little or no preparation in this area. Studying talented principals and educators who successfully create caring, safe schools is another area requiring more research. While evidence-based programs matter, there is much to learn from the people who implement them effectively.

What are schools doing to improve safety?

Recent studies show that schools are using a wide range of strategies to improve safety. These include evidence-based programs such as social-emotional learning, restorative justice, school-climate initiatives, anti-bullying programs, and systemic efforts like PBIS (positive behavioral interventions and supports) and MTSS (multi-tiered system of supports). Schools are also increasing capacity by hiring more social workers, psychologists, and counselors to support these programs and address mental health needs.

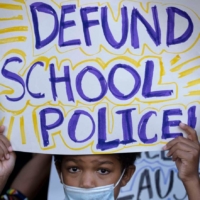

At the same time, many schools rely on law-enforcement approaches related to school shootings: shooter drills, lockdown practices, and employing school resource officers or police. Schools are also “hardening” their campuses with metal detectors, cameras, high-tech shooter-detection systems, and strict safety policies. In some states and districts, school staff are now permitted to carry firearms. These developments largely stem from the ongoing failure to reduce school shootings.

Please explain the difference between voices and data in your work and why it matters for keeping students and schools safe.

The core of creating a successful school action plan is closely listening to the voices of students, teachers, parents, and the community. Without this, most programs and strategies fail. In many schools, only a small number of people openly express concerns, even though school communities hold diverse views about safety. In the intervention programs I developed with my colleague Rami Benbenishty, we begin with students’ voices. Students create qualitative maps of the school and describe times and spaces where they feel safe or unsafe, explain why, and offer recommendations for making unsafe areas more welcoming. We do the same with teachers and parents. We also conduct short surveys with quantitative and qualitative questions. These anonymous results are presented back to the school and become the basis for discussion and action planning.

People often disengage when they hear the word “data,” seeing it as distant. I challenge educators to imagine each response as a child’s voice about safety, drug use, suicidal ideation, or ideas for improving school. When seen as collective voices, the information becomes personal and encourages engagement. We frequently observe teachers shifting their practices when they realize many students — through surveys and maps — are struggling with mental health issues, substance use, or victimization. At that point, it is no longer data but a message from students, teachers, and parents. These voices and recommendations become the foundation for meaningful grassroots change.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!