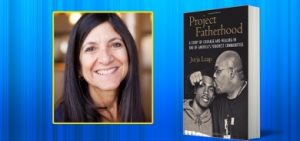

Leap Honors Dads in ‘Project Fatherhood’ In her new book, Social Welfare professor Jorja Leap tells stories of former gang members who have decided to commit to their roles as fathers

By Adeney Zo

UCLA Luskin Student Writer

In her first book, Jumped In, Social Welfare professor Jorja Leap told the story of her life as a “ganster anthropologist,” and an observer and advocate for the young men and women caught up in the life of gangs. Her new book, Project Fatherhood, is about the life that some of these men have chosen to live after leaving the streets—as fathers to their sons. In an environment where involved fathers were hard to find, these men are committed to changing the dynamic for their children.

Leap sat down for this Q&A in advance of the book’s release party on Thursday, June 4.

How did you first become involved with Project Fatherhood?

I’ve known Mike Cummings [co-facilitator of Project Fatherhood] for 15 years. I wrote about him in my first book, and he called me about this group he was starting with the Children’s Institute. They needed a social worker to co-lead the group, so I literally jumped at the chance. I have been actively involved as a social worker and researcher, trying to help people all of my life.

What made you interested specifically in the Watts community and this project?

I got my MSW at UCLA in 1978 and started working in Watts. I see it as the community I belong to—my parents are from South LA and I was born and raised there for part of my life. I’m committed to it.

How does Project Fatherhood work differently from other gang intervention programs? What makes it effective?

It’s completely different, especially in its development. Without any organization or guidance, these are former gang members who wanted to reach out [to their children] and be fathers. We all know that the absence of fathers is a huge youth risk factor that leads to a lot of problems in school and community-based activities. It’s a terrible burden for young people that affects them throughout their lives. Project Fatherhood is more like a gang prevention program. Youth with incarcerated fathers find father mentors [through Project Fatherhood], which softens the cycle of life for the next generation. This is also a way for men who were former gang members to father one another. They all grew up without fathers, and now they are helping each other learn to be fathers. It’s so incredible to witness and be part of this for 4 years.

One of the key research findings is the kind of strong leadership that already existed in community. If we are looking at how to rebuild communities in the future, we need leadership that comes from within the community.

How does this book differ from Jumped In?

Jumped In is about what studying gangs taught me. It was very personal. I discussed raising my own child, so it was a memoir as well as a humanizing story of gang members. This book [Project Fatherhood] is about the project—there’s a little about me but mostly it’s about them and the issue of poverty.

Working in the field, teaching at UCLA, and publishing a book each have a different scope of impact. What sort of impact do you hope to make with Project Fatherhood, and what do you hope readers will ultimately take away from the book?

My goal is that the program will be funded and supported. All the proceeds from the book go to Project Fatherhood, the men who really deserve this kind of funding. I want the stories of these men to be out in the world. We also need to build leadership in the community, and we have to be the support for what exists in that community. UCLA Luskin plays an important role in this—the role of wanting to support and conduct research within these communities. It’s wonderful to be here and be part of a program working to build that kind of community strength.

I want readers to understand what the experience of these men is truly like, who these men are as human beings. I want to show the “new Jim Crow,” this issue of men of color being incarcerated for long periods of time, and what it cost them, their family and community. I also want people to have hope as they read and see how devoted these men are—this is not a problem story, but a hope story. I want to show that strength and dedication is out there.

How did the fathers react to your decision to write a book about them?

I was a little bit worried when I brought it up, but they were very positive, very proud and excited. In the past when I did Jumped In, I worked carefully to disguise the interviewee’s identities. As I interviewed the fathers [from Project Fatherhood] and asked how they felt about being named, they all said, “Don’t worry, you can use our names. Tell the truth.” They were so honest and so open in wanting to share. It was an overwhelming experience, seeing how meaningful their commitment was to the program.

The truth is, I always felt like I belonged in Watts, and this project strengthened my attachment, belief and commitment. People who read the book will understand that we [the fathers and I] had big fights—it was not all sunshine and roses. We really struggled, but we were very open about how we made each other angry. I could have never imagined that through the past four years, this closeness and understanding would develop.

How can the public contribute to a solution for gang violence and poverty in communities like Watts? Do you recommend any programs or resources that offer the chance for people to take action?

I am hoping to bring support for the programs that already exist, that are there and are working. I hope this book will help leadership development and economic development. These are good fathers, good providers who want jobs. They don’t want to raise kids on the county and public support—they want to make a living. It’s quite striking; many people think they want to live on welfare, but that is the farthest thing from the truth.

As part of the UCLA Luskin faculty, I will be sponsoring a book party on June 4. This is an all-day event, and we’re even bringing youth from Watts to tour UCLA and work out with the football team. Copies of the book will be available before the release date on June 9, or Father’s Day. [The event] is really not about me, but the fathers who will be there to speak about their experiences. I really urge the UCLA community to come out and hear their voices.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!