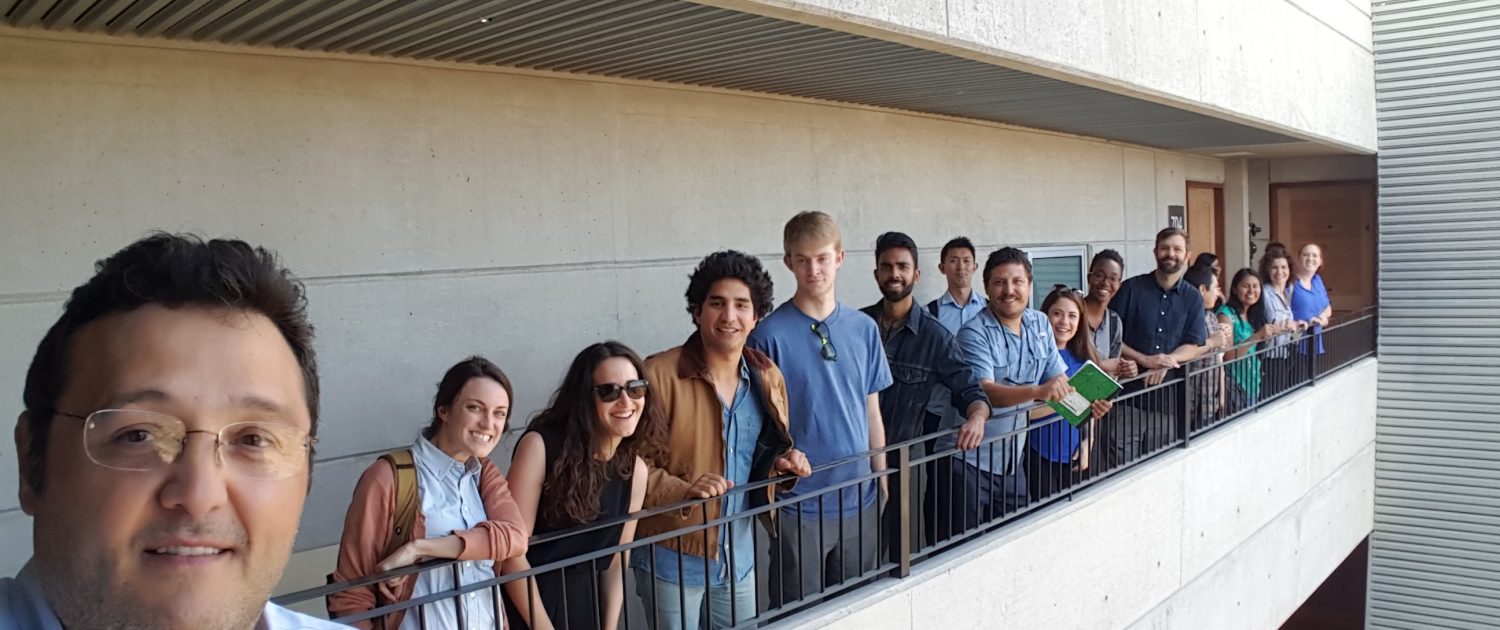

Students’ Visits to Mexico Produce Real World Insights Urban Planning fieldwork course taught by UCLA Luskin's Paavo Monkkonen completes its study of housing crisis in Tijuana

By George Foulsham

UCLA scholar Paavo Monkkonen teaches classes covering housing policy, applied microeconomics, and global urban segregation, but much of his research focuses on Mexico. He has been working in Mexico – and in Tijuana – since 2003 and has served as a consultant to the Mexican government on housing policy issues.

So when Monkkonen, an associate professor of Urban Planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, speaks about housing problems in Tijuana, people should probably pay attention.

“In the last 20 years, Mexico has built a lot of suburban housing and a lot of it’s empty,” Monkkonen said. “There is a major housing crisis right now.”

It’s also a teachable moment for this college professor, who created a course that took his students to Tijuana to examine the housing that federal policies have financed. The course provided the opportunity to offer real-world urban planning lessons to UCLA Luskin students.

“I had the idea of doing a case study of Tijuana’s housing system and how federal policy is played out in a local context,” Monkkonen said. “The course is different from many, though, because it’s a studio course that is a practice-based, problem-solving type of course. It’s not about me teaching; rather, I am working with students to actually do research and provide policy recommendations.”

The goal of the class, “Special Topics in Regional and International Development: Increasing Infill Development in Tijuana, Mexico,” was to determine how the institutions of Tijuana’s property market shape the implementation of the new federal urban policy designed to limit expansion and increase density in the central parts of Mexico’s cities.

With financial assistance from UCLA’s Urban Humanities Initiative and the Latin American Institute, Monkkonen put together the 2016 studio course in which students made two trips to Tijuana during the spring quarter.

“They were in five different groups, working on different aspects of the housing production system — infrastructure, planning, real estate development, the social culture around the consumption of housing, and formality,” Monkkonen said.

The students’ first visit to Tijuana included meetings with:

- A representative of the government housing finance agency

- A real estate broker who does consulting work for the government

- A representative from a regional economic development consulting company, focused on industrial development

- Local academics and graduate students

The students also did two site visits, including a tour of a new middle-class apartment building and of a new social-interest housing development.

“The focus of the class is the new federal policies that are trying to curtail sprawl and promote urban compact density,” Monkkonen said. “These policies were enacted in part because 30 percent of the new houses are empty. Despite the new message from the federal government to build more compact cities, they’re actually still building a lot of sprawl.”

The site visited by the students was a perfect example of the housing explosion in Tijuana. In an area that is miles from the edge of Tijuana, a developer is building about 50 houses per week, next to several developments full of abandoned houses.

“They have 5,000 built and the master plan of that company is to build 50,000 homes,” Monkkonen said. “The federal housing agency supports it, so it’s a strange system of bad decisions and government gone wild.”

Construction of new homes in Tijuana — and all over Mexico for that matter — is built on a system that encourages rampant development, Monkkonen said.

“Developers can make a lot of money building small, inexpensive houses in the urban periphery,” he said. “The vast majority — 70 percent — of housing finance comes from a federal government agency that operates like a pension fund, although the pension payout is very low. So every salaried worker has to pay into it, like a social security contribution, and then they are heavily pressured to get a mortgage. In many cases people use this mortgage even if they don’t want a house.”

The students also drove past two failed housing projects on the way back from Natura into Tijuana, developments of about 3,000 homes. “Some sections are half-built,” Monkkonen said. “There’s empty land, parts that are half-empty, covered in graffiti — not a nice environment, with a lot of trash around.”

It didn’t take long for the students to recognize the issues that led to two decades of overbuilding.

“The issue with Tijuana is that the institutions don’t really talk to each other,” said Katie Cettie, one of the students who authored the Real Estate Practice and Finance section of the report. “What the federal and the state do is very different from what actually happens at the city level. Everyone has their own agenda, so it’s really hard to get them to come together.”

Among the findings and recommendations in the recently released 131-page final report:

- Local land use planning and development institutions are disconnected from federal housing policies.

- Federal housing policies are designed more for the stimulation of the economy from the national perspective.

- The flow of communication from local to federal and federal to local is unclear among agency employees, and the framework for this process is not well understood by officials or the public. The roles of federal, state and municipal agencies are largely distinct and lack effective coordination.

- In Tijuana, the private sector has historically driven growth and economic development. Today, these actors continue to be overrepresented in the planning process.

- The importance of political linkages and alliances at the local level continue to stifle the ability for sustainable urban development in Tijuana.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!