Tapping People’s Passions to do Something Good

By Les Dunseith

By mid-March, the World Health Organization had declared COVID-19 a pandemic, UCLA classes had moved online and university employees in non-essential roles were working remotely. Soon after, on April 1, the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge, or CNK, based at UCLA Luskin issued its first research report about the health crisis.

By late September, researchers affiliated with CNK had released more than a dozen COVID-related studies on their own or in partnership with other centers at UCLA and elsewhere in academia. Roughly, that works out to an astounding pace of one new study every two weeks.

The first report, “Implications of COVID-19 on At-Risk Workers by Neighborhood in Los Angeles,” was released in conjunction with the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Initiative. It delved into census information to identify the neighborhoods most vulnerable to economic hardship from the pandemic. Poorer ethnic areas would fare worst, the study predicted.

Two weeks later, a CNK study identified Latino neighborhoods as being less likely to receive federal economic stimulus funds. By mid-May, a CNK report had determined that the census tracts that were lagging behind in the 2020 enumeration were the same areas of L.A. hit hardest by COVID-19. Additional studies soon focused on renter displacement, a shortfall in unemployment coverage for workers in disadvantaged communities and other topics related to equity and social justice amid the pandemic.

Such a prolific output of timely research is impressive, but it’s even more so when you consider that much of the project, known internally as the COVID-19 Equity Research Initiative, was completed without prior funding.

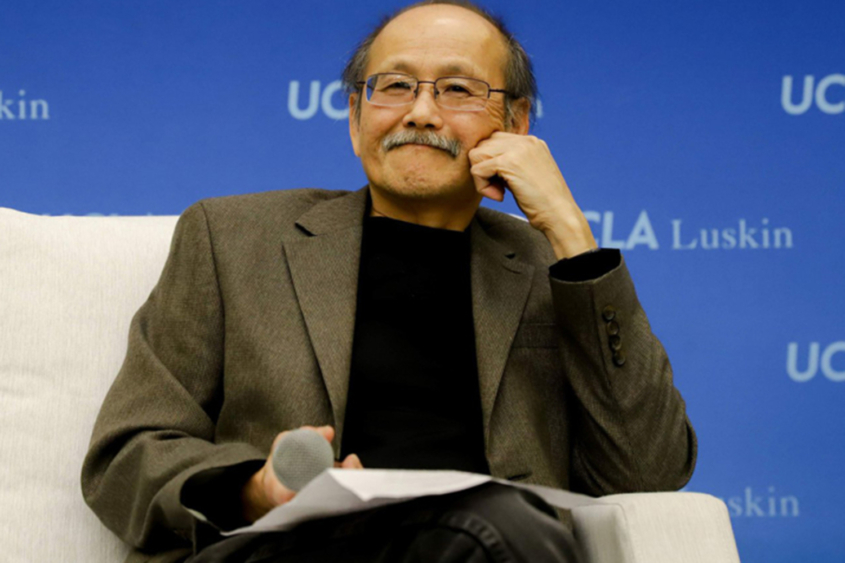

“The way we work is that we tap into people’s passions and commitment to doing good,” said Paul Ong, CNK director.

“I call on my friends, my colleagues and my family, offering them an opportunity to make a contribution and make a difference by producing these analyses and informing the public.”

Ong said he had a sense when he first heard about the novel coronavirus that it might have a huge impact, and as early as February he began hearing from people in the Chinese American community that they were being adversely impacted, including being blamed for the outbreak.

“We heard anecdotal evidence that indicated that, indeed, this might be a very profound crisis emerging,” Ong recalled.

But when he asked for empirical evidence, most people didn’t have any.

“It’s partly that I’m just inquisitive,” Ong said of his nature, but soon he was devoting time and effort to finding ways to investigate what people were saying, looking for data to help document the unfolding crisis.

Delving into the impacts of the pandemic on marginalized populations aligned perfectly with Ong’s reasons for starting CNK in the first place. The research center builds on his background in social welfare and urban planning with the idea of “trying to understand the nature of inequality in our society from a very empirical, quantitative approach,” he said.

“We believe that the way we move forward to a more just society is by fully understanding the challenges before us,” Ong said. “It is good to think about utopia, but the problem with just thinking about utopia is it doesn’t anchor you into the reality of what needs to be addressed.”

The team at CNK is small, numbering between two and two dozen, depending on funding and how many student workers are available. Ong, who retired in 2017 but has continued as a research professor, said the research center has long sought to understand the nature of inequality, how it’s produced and reproduced over generations, and how it takes form in different sectors — housing, employment, education, health.

“Indeed, if [the pandemic] was going to have a profound impact on society and a profound impact on disadvantaged neighborhoods and populations, then we believed that we could make a difference in terms of working to generate additional insights,” Ong said.

Soon, Ong was enlisting help from friends and colleagues, including his wife, Elena, a public health expert, and his son, Jonathan. Both worked pro bono on some reports despite not being directly affiliated with the University of California.

They asked questions: How can we identify the population most at risk? How can we identify those not likely to receive the type of support that’s necessary? Next, without stopping to seek funding, they sought answers.

Ong noted that the grant funding process can take months or years. “But we’re not working in normal times,” he said. “The crisis is unfolding in real time. We’re working during a time where decisionmakers and community leaders and other stakeholders need the data today.”

So, Ong found help wherever he could. In some cases, he was able to obtain funding and research assistance from colleagues at UCLA, including people like Professor Ananya Roy, who leads the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy.

“Amidst difficult times, the scholarship pioneered by Professor Paul Ong and the Center for Neighborhood Knowledge has been a guiding light, demonstrating how and why rigorous research has an important role to play in shining a light on structures of inequality and making the case for the policies that must address such oppression,” Roy wrote about her team’s involvement in several of the pandemic-related reports.

As the pandemic continues, so will the research by CNK.

Ong is hopeful, knowing that a vaccine will be widely available soon and that society will regain some sense of normalcy thereafter. But the work will not be done.

“What I’m concerned about is that the legacy of the damages from the pandemic is not going to disappear,” Ong said. “We’re going to have to live with those inequalities. It has had profound impacts on people and households.”

Some impacts are obvious and visible. Others, such as the likely census undercount in low-income communities, will have repercussions that may not materialize until years later.

If there’s an upside of the pandemic for Ong, it’s taking gratification in the collective effort.

“In these dark days, it’s great seeing people being willing to volunteer and do the hard work and not receive compensation for it,” Ong said. “I am very grateful to our partners at other centers who were willing to step forward to help us.”

With a wry smile, Ong summed up his formula for success: “We depend on the kindness of strangers.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!