By Mary Braswell

The community garden launched by the Watts Leadership Institute (WLI) a year ago is growing, thriving, bearing fruit.

The same could be said for the institute itself.

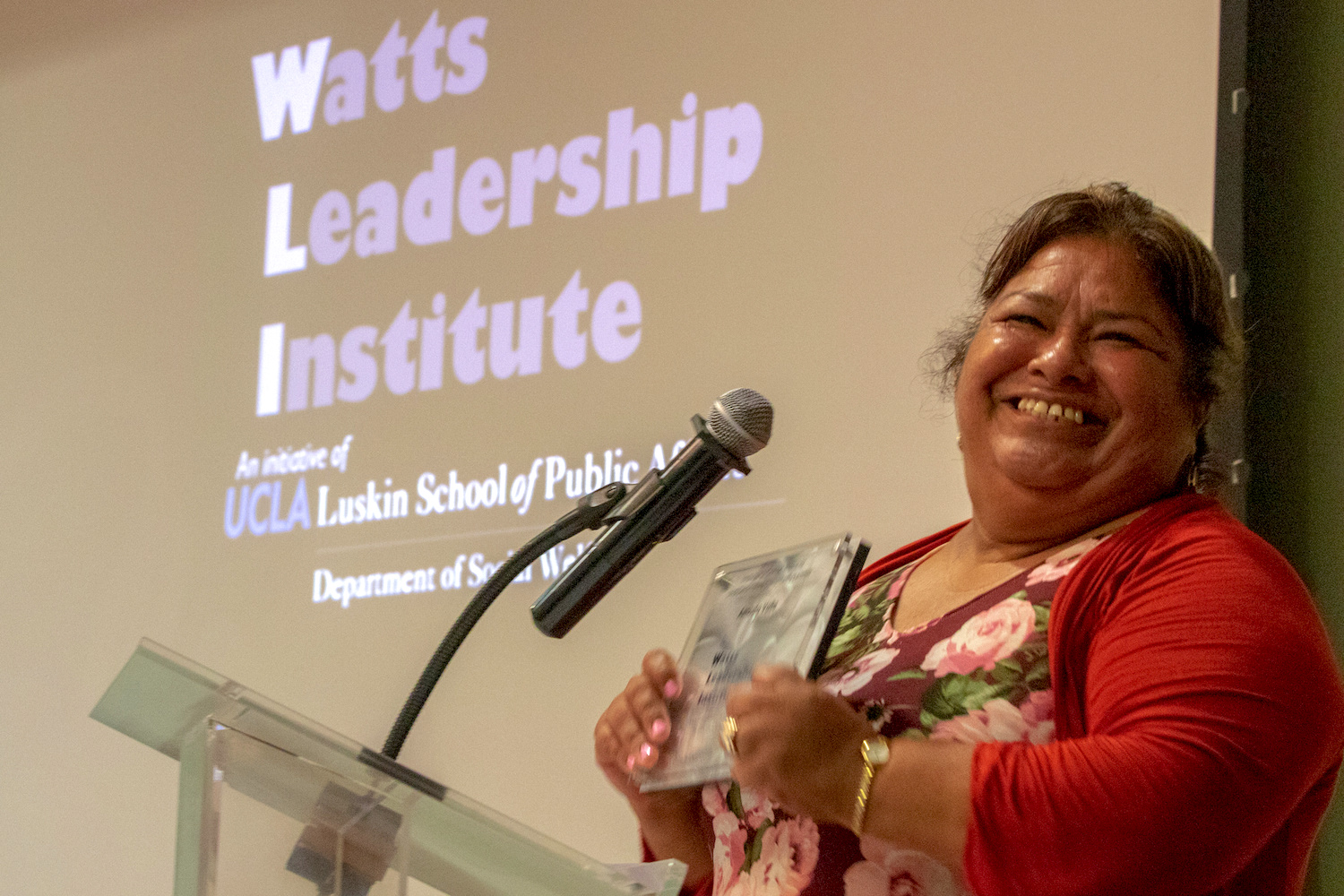

Since the start of 2018, the UCLA Luskin-based WLI has received several grants totaling more than $650,000 that will allow it to expand its core mission of empowering the community leaders of Watts.

“We’re absolutely thrilled,” said co-founder Jorja Leap, adjunct professor of social welfare. “We’re finding great support for this model, the idea that we want to lift up and help the small nonprofits and real community leaders in these marginalized communities.”

Along with Karrah Lompa MSW ’13, Leap founded the institute in 2016 with a two-year $200,000 startup grant from The California Wellness Foundation.

Since January, WLI has received new and increased investments:

- An additional two-year grant of $250,000 from The California Wellness Foundation is an expression of confidence that its initial investment was effectively used in the community.

- The Weingart Foundation is providing $200,000 for the next two years to support its efforts in Southern California communities most deeply affected by poverty and economic inequity.

- Ballmer Group provided $150,000 over two years. Ballmer Group supports efforts to improve economic mobility and has invested significantly in direct services and capacity building in the Watts-Willowbrook area.

- GRoW@Annenberg has invested more than $50,000 this year as part of a multiyear commitment for the WLI GRoW Community Garden. It has also provided generous additional funding and technical assistance to enhance WLI community engagement and outreach. In addition, GRoW’s founder, Gregory Annenberg Weingarten, has awarded almost $100,000 directly to Watts community leaders working with WLI.

These continued philanthropic investments will “take our mission to another level,” Leap said. Lompa added that “having the support of these leading philanthropic institutions reinforces both the need for WLI and the impact these leaders are making in Watts.”

“We are grateful for these new funders and grants because they help diversify WLI’s overall funding, helping us lead by example when encouraging WLI leaders to diversify their own funding streams,” Lompa said.

The funds are quickly being put to use on the ground in Watts. WLI works with community leaders who are already making a difference and provides them with the tools, resources and training to be more effective — including tutorials on using tablets to keep their books as well as tips on navigating the Southern California policy and philanthropic landscape.

“These are the people that the community listens to and follows,” Leap said of the first cohort of 12 Watts leaders supported by the institute. “They live there, they work there. But they’ve never had the capacity to really do the work of which they are capable.”

The key for WLI, she said, is to listen to people who are acutely aware of what their neighborhood needs. WLI builds on this knowledge by responding with tangible help to sustain the leaders and their efforts.

Leap told the story of WLI cohort member Amada Valle, a community organizer and advocate for residents of the Jordan Downs public housing development. “Amada is teaching women to sew and to create women-led businesses,” Leap said. “And what do you need if you’re teaching women to sew? Sewing machines.” Thanks to funds allocated by The California Wellness Foundation for direct service reinvestment, Valle received a grant from WLI to purchase six sewing machines.

“You would have laughed if you had walked into the Luskin development office and seen all these boxes of sewing machines, all piled up,” Leap said.

Doing good works is contagious, WLI has found. Los Angeles City Councilman Joe Buscaino donated office space to the institute. The Johnny Carson Foundation funded an MSW internship in Watts. The UCLA Luskin IT team offers technical support, bringing community leaders to campus for tutorials.

“That’s really our dream — to have everybody working together and leading within their community,” said Leap, who has been active in Watts for 40 years, since she attended UCLA for her BA, MSW and Ph.D.

“With WLI, UCLA Luskin has a 24/7 presence in Watts. This is not lip service, and we don’t want to be a temporary program. We’re part of the community, and we want to be,” she said. “We’re honored to be.”