By George Foulsham

WATTS — If you’re searching for the heartbeat of the UCLA Watts Leadership Institute, look no further than 10360 Wilmington Ave. in Los Angeles. What was once a liquor store is now the home of the multi-faceted Watts Century Latino Organization.

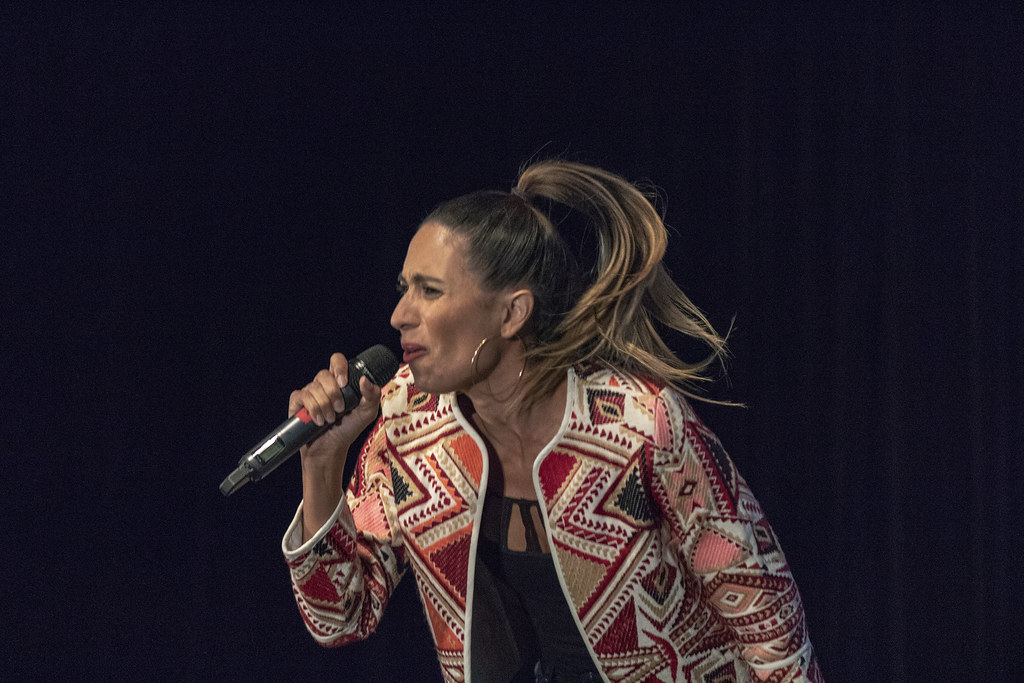

On a recent Saturday, more than 70 volunteers gathered here to help with a grassroots task: assemble and plant a community garden. The event was part of the citywide Sharefest Community Workday, but it represented much more for Jorja Leap, an adjunct professor of social welfare in the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, and for the Watts Leadership Institute’s first cohort — community members who hold the key to deepening the indigenous leadership of Watts.

“This is the beginning,” Leap said as the volunteers spread mulch around four large planter boxes. “We’re going to be bringing in youth from the various middle and high schools throughout the area. They’re going to be learning about gardening, they’re going to be learning about healthy eating, and they’re going to be developing strategies for contributing to their community.”

It’s just one example of what the Watts Leadership Institute hopes to bring to a part of L.A. that Leap has been engaged in since she was a social welfare graduate student at UCLA in the 1970s. Leap and project partner Karrah Lompa MSW ’13 have launched an institute that’s making a 10-year commitment to Watts.

The Watts Leadership Institute received its key initial funding through a two-year, $200,000 grant from the California Wellness Foundation. In turn, the WLI GRoW Community Garden is supported by a two-year, $100,000 grant from GRoW @ Annenberg, a philanthropic initiative led by Gregory Annenberg Weingarten, dedicated to supporting humanitarian efforts across the globe as well as innovative projects in health, education, the arts and civic & cultural life. The Sharefest Community Workday provided additional support for the community garden from Sharefest, the Mars Corporation and Our Foods.

“This kind of a public-private partnership, along with the research attached to it — and the building of the Watts community — really represent the best of how all of these different factors can come together,” Leap said. “It represents part of UCLA’s continuing and growing commitment to communities like Watts that need our involvement, our engagement, our organizing, our research. We’re also learning from them and being taught by them.”

The garden project marked the first time that the institute’s cohort was able to engage Watts residents — and many other volunteers — in the community garden, according to Lompa. “The community was able to get their hands dirty, to help make the garden a reality and to take ownership,” she said. “The volunteers included cohort members, institute fellows, UCLA students and alumni, community members, corporate volunteers and representatives from the Annenberg Foundation. It was everybody coming together to launch the community garden.”

Among the community members in the institute’s first cohort are Pahola Ybarra and her father, Arturo Ybarra. Pahola is program manager and Arturo is the founder and executive director of the Watts Century Latino Organization, which has galvanized the growing Latino population in Watts. The center’s programs are credited with helping to build significant bridges between Latinos and African-Americans. To accomplish this, Pahola and Arturo are among the community leaders recruited by Leap as part of the initial leadership cohort in the institute.

When she approached the Ybarras about becoming part of the institute, Leap asked for guidance about the best way to bring Latinos in the community aboard. Pahola suggested teaching Latino leaders how to start a 501(c)3 nonprofit as a way to “teach them how to do bigger things in the community,” Ybarra said.

It’s only 2.1 square miles, but Watts has more than 190 nonprofits. The problem, according to Ybarra, is that there has always been overlap in the services offered by the various nonprofits.

“What Watts Leadership did was to help us come together, to put our resources together, and be an example for the rest of the nonprofit and leadership community in Watts,” Ybarra said. “It’s been an amazing effort to help us grow, and to help us get out of our own way. It encourages us to reach for as much as we can and do as much as we can in the community.”

Leap often draws upon social welfare professor Zeke Hasenfeld’s Luskin research, which initially characterized Watts as a “nonprofit desert,” but she’s hoping the institute can change that perception by training the first cohort of leaders who will then share their knowledge with a second and a third generation. One of the institute’s goals is to build a comprehensive infrastructure of nonprofits in Watts and use it as a model to build indigenous leadership. That was part of the strategy of the WLI GRoW Community Garden and it was kicked off on this volunteer day.

“This probably doesn’t look like an economic development project now,” said John Jones III, field deputy for Los Angeles City Councilman Joe Buscaino, who represents Watts. “But in the future, when things are growing from here, different businesses might come and buy the fruits and vegetables from here that will help this nonprofit thrive.”

Jones credits Leap and Lompa with teaching community members how to build a better community. “When the Watts Institute grows, this organization will be stronger, it will be better, and the Watts community will be better because of the lessons they learned,” Jones said.

That legacy approach is key to the success of the institute, Leap said.

“We will serve those within the community who will lead and will teach,” she said. “This way, we not only build capacity, we build a continuum of leadership that is cross-generational. Luskin is not going to leave, but we ultimately want Watts in the lead.”

Cohort member Kathryn Wooten, the founder and executive director of Loving Hands Community Care, is a lifelong resident of Watts whose organization was struggling until she was recruited by Leap to be a part of the institute. As part of the cohort training, Wooten and others were provided with computers and trained in how to use them.

“It’s almost too good to be true,” Wooten said. “Since I’ve been a part of it, my organization is more professional. I have all the things I need to run a business because of the cohort and their guidance. I now know how to use a computer.”

Leap’s approach to this project is motivated by a powerful sense of duty.

“This is my way of paying back,” she said. “I did come here in 1978 as a very callow MSW student, and the Watts community took me under its wing and taught me. UCLA afforded me the opportunity to learn here. This community has given a great deal to me, and it is my responsibility and my honor to pay that back, to listen and to really serve in the most meaningful way that I can.”