Decoding the Apple v. U.S. battle Public Policy professor John Villasenor breaks down the background, key points and possible consequences of the iPhone legal dispute

By George Foulsham

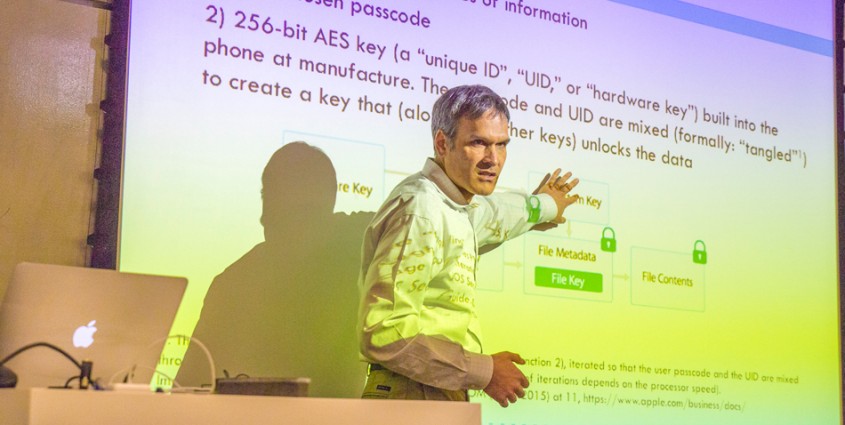

During his discussion of the much-publicized iPhone standoff between Apple and the U.S. government, UCLA Luskin Public Policy professor John Villasenor said his main goal was to present the facts of the controversial case, and not to focus on his personal opinion. But, at the end of the discussion, after walking the audience through the background, technology and possible consequences of the legal battle, he did disclose what he thinks the outcome might be.

“I can’t imagine that the government is going to force a team of Apple engineers to drop everything and create a bunch of new code,” Villasenor, a professor of public policy, electrical engineering and management, said. “I have a hard time seeing it’s going to go that way.

“I might be wrong,” he added. “At the end of the day, if Apple refuses, there may be sanctions. They could fine Apple. They could hold them in contempt of court. You could jail the responsible person. It’s just hard to see that would happen to Apple.”

Villasenor’s talk, held at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, attracted students and scholars who, like the rest of the country, are fascinated by the many twists and turns the case has taken.

“This is a perfect example of why so much of what we do at UCLA crosses these boundaries — technology, policy, law and business — and how it intersects in this way that quite literally is dominating the headlines,” Villasenor said.

The latest development occurred Thursday when Apple filed court papers claiming that a federal judge had overstepped her authority and violated the company’s rights by ordering the company to help unlock a terrorist’s phone. “The ground is moving underneath us as we sit here,” Villasenor said of the rapidly unfolding legal war.

On Feb. 16, a federal magistrate issued an order compelling Apple to assist the government in bypassing the security features of an iPhone 5c used by one of the shooters in the December 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack. Apple opposes the order, arguing that the government’s demand to “build a backdoor into our products … would undermine the very freedoms and liberty our government is meant to protect.”

Villasenor, who’s also a visiting professor of law at UCLA, covered the key points in the dispute, including an overview of the government invoking the All Writs Act of 1789 as a justification for compelling Apple to provide access to the phone. “What other document happened in 1789 that we like?” he asked. “Anything else come to mind? Like the Bill of Rights?”

Speaking of the government’s use of the All Writs Act, Villasenor said that “as far as I know, this is the first time the government has ever ordered someone to write code.”

He explained that one of the ways to access the information in the phone is through the use of a “brute force attack” — entering passcodes until you get the right one. “The problem is that iPhones have security features designed to thwart those attacks,” he said. So if someone tries to enter passcodes 10 times, and they’re unsuccessful, the phone can erase a file system key, making it impossible to decrypt data on the phone.

However, if the government had access to a phone containing the software it is trying to compel Apple to create, a brute force attack might not take long to unlock all of the data.

“If you have a four-digit passcode, it will only take you about 15 minutes to go through all of those combinations, actually probably less,” Villasenor said. “After 7 or 8 minutes, you could probably get in. A six-digit passcode could be found in about a day.”

But since iPhones running recent versions of iOS also allow longer passcodes, including alpha-numeric combinations, the challenge could be daunting. “The numbers quickly explode,” he said. For a six-digit alpha-numeric code, Villasenor said it would take “five and a half years to calculate all combinations … according to Apple.”

The next steps in the dispute include additional court filings, a March 22 hearing in a Los Angeles federal courtroom, followed by a decision by a magistrate, inevitable appeals in district and circuit courts, and maybe an appeal to the Supreme Court.

Among the consequences of the case, according to Villasenor, are what other, potentially oppressive governments might do if Apple were to lose the case and be forced to provide what the U.S. wants, and the inevitability that we all will wind up with more secure phones in the future.

“This is a compelling test case,” Villasenor said. “This case is going to be incredibly important.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!