By Stan Paul

Just one visit. For those whose lives are entangled in the pipeline of the juvenile and adult justice systems, the life-changing meeting might come from a family member. It could be a psychologist. Or a chaplain. Or it could never come at all.

For many, though, the visitor is a volunteer — someone who can make the difference between continuing a downward spiral through the criminal justice system and turning a life around.

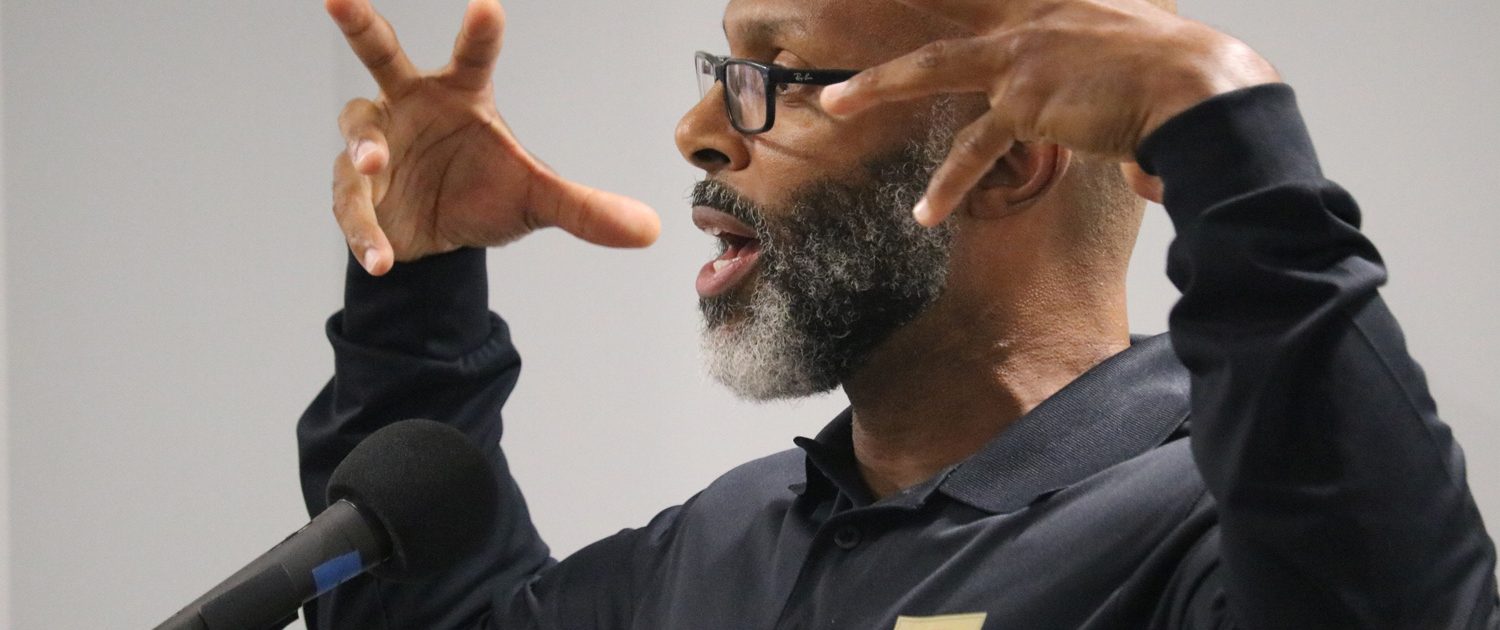

“The cycle continues until someone breaks it,” said Ernst Fenelon Jr., who was part of a Nov. 3 panel speaking about volunteers who help those incarcerated in America’s juvenile detention centers and adult prisons. The event also launched a new book co-edited by UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs Social Welfare professor Laura Abrams. It was sponsored by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs Department of Social Welfare, the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin, and the UCLA Justice Work Group.

New book co-edited by UCLA’s Laura Abrams.

The book, “The Voluntary Sector in Prisons: Encouraging Personal and Institutional Change,” was published “to highlight many examples of great practice, of volunteer programs that make a real difference behind bars … and impacting not only those who take part in the programs, but the volunteers,” Abrams said. She was accompanied by one of her three co-editors, Emma Hughes, an associate professor and chair in the Department of Criminology at California State University, Fresno.

“This event, and the book itself, is intended to honor volunteers in jails and prisons, juvenile and adult institutions, who devote their personal and professional time, travel long distances and overcome numerous bureaucratic hurdles to reach out to those locked on the inside, whose humanity and dignity is often limited by the very condition of incarceration itself,” Abrams said in her introductory remarks.

Abrams said that the work of her colleagues and co-editors highlights many examples of great practice, impacting not only those who take part in the programs, but the volunteers as well. “Unfortunately, this evidence of good practice is not well-known, so other volunteers have to keep reinventing the wheel, rather than benefitting from the experiences of others,” she said.

The co-editors pointed out that volunteers themselves are very diverse. They may be formerly incarcerated, currently incarcerated, teachers, musicians, artists, students or people of faith. A unique feature of the book is that it includes the voices of a number of people currently serving time, in addition to the 19 contributing authors from the United States, Canada and Britain.

“You may be that one person,” said Fenelon, whose 25 years of experience with the California prison system includes more than 14 as an inmate. He is now the program coordinator for the Prison Education Project (PEP), a “prison-to-college” program that seeks to enhance the educational experience of inmates and parolees while providing practical tools for reintegration.

“You’re here because it is a calling,” Fenelon told the audience of academics, social welfare students and volunteers, some of whom also had been wards of the foster care, juvenile justice and adult prison systems in California. “The best people to speak are the volunteers,” continued Fenelon said. Like himself, they “speak from a voice of unique experience,” and “sat where they sat” and they strive to “reconnect [those incarcerated] to their humanity.”

He was joined by Rosalinda Vint, president of Women of Substance and Men of Honor Inc. Vint, who grew up in the foster care system, has been “that one person,” Hughes said in introducing her.

“All of us have a friend or relative touched by the system,” said Vint, whose nonprofit organization provides mentoring, leadership training and other services for the Department of Juvenile Justice Ventura Youth facility. The former corporate executive, who left a successful 25-year career to reach out to foster youth, said it is a privilege to serve those who, like her, have suffered abandonment and loss. Recounting her own and her siblings’ experiences within the foster care and criminal justice systems, Vint paused, as her voice cracked with emotion. She continued, “This has changed my life, what I do. I wish someone would have come for me, looked me in the eye and said it is going to be OK.”

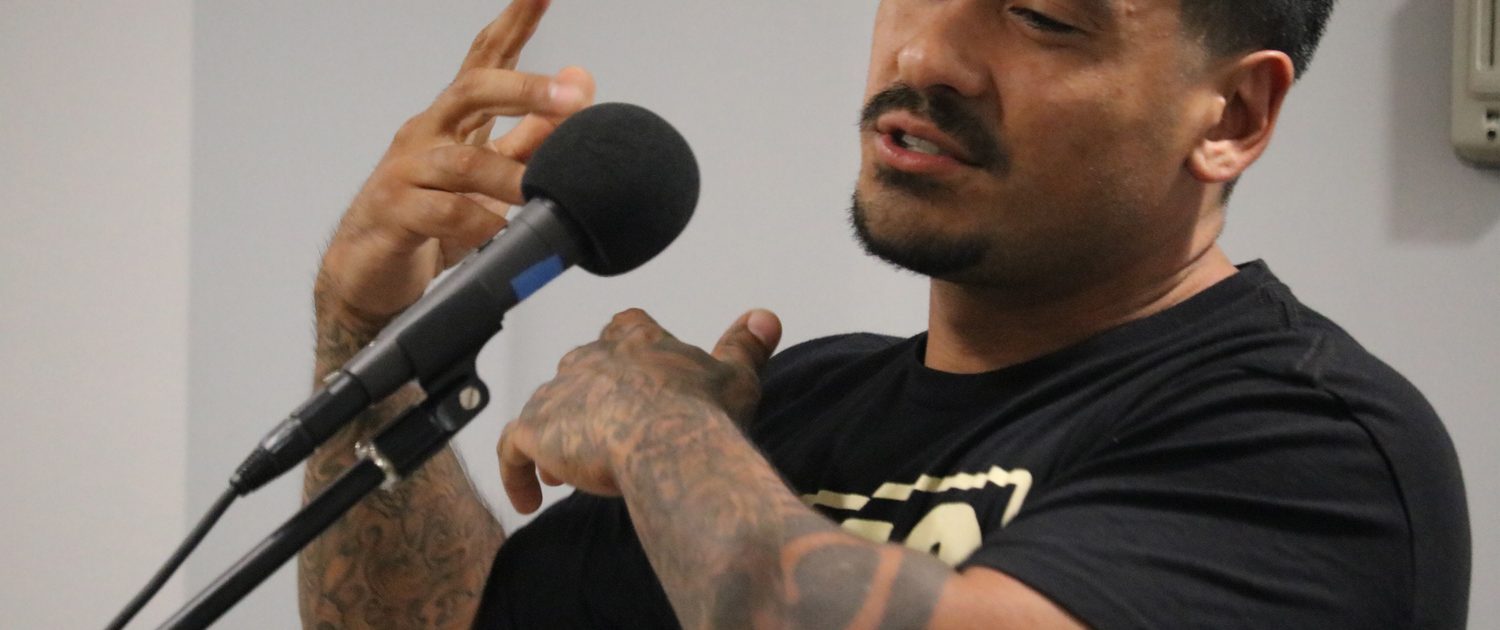

The relationship between two of the event’s speakers, Felix Miranda and Matthew Mizel, is an example of the significant difference that volunteering can make in the lives of both volunteers and those they help.

Miranda was raised in Nicaragua and he “saw things that no kid should see.” He was angry when he came to the United States, eventually ended up in trouble and lost 13 years of his life to the prison system in California. Mizel, a native of New Jersey, had a successful career in the entertainment industry before becoming a volunteer with Inside Out Writers in 2003, teaching creative writing in juvenile and adult facilities.

They met while Miranda was imprisoned, and the experience was transformative for Mizel, who was volunteering with the nonprofit organization founded in 1996. Mizel is now a doctoral student in the Luskin School’s Department of Social Welfare, where his research focuses on ways to reduce racial inequality in the justice system.

“I had to grow out of that phase,” said Miranda, who was recently released from prison and is now a member of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC). “You can make a change.”

Miranda said that at first he couldn’t understand why Mizel kept showing up to his prison visits, and more than once asked him why he would do this.

“He came every week — that’s what impacted my life,” said Miranda, who also is now a member of the Inside Out Writers alumni project. He credits Mizel “for the love and friendship he showed me,” and the writing program for the positive changes he experienced.

“Don’t just show up,” Miranda said about volunteers’ need for perseverance and engagement. “It’s the follow-up that matters.”

According to Hughes, the book is also intended to show correctional officials and policymakers how valuable this work is. “All too often volunteers are confronted with insurmountable hurdles in terms of red tape and bureaucracy when trying to access facilities.”

Hughes added, however, that she is encouraged by recent changes.

“I am heartened that this year, CDRC (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) has a mandate to establish a volunteer advisory committee at every adult prison, with the intention of better supporting volunteer-led programs,” Hughes said.

The evening’s presentations also included a moving spoken word performance by Harry Grammar, who brought students from his New Earth Arts and Leadership Center, a comprehensive re-entry center serving 2,500 young people each year who are incarcerated in Los Angeles County detention centers and placement homes.