Oil and Gas Companies Sacrificing Plastic-Burdened Communities

The UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation has released a new report examining the links between plastics, fossil fuels and inequitable exposure to environmental hazards. Titled “What Defines a Plastic-Burdened Community? — Part II,” the report is authored by Veronica Herrera and Daniel Coffee.

The analysis highlights how communities located near refinery infrastructure face disproportionate exposure to pollution, despite California’s reputation for climate leadership. Emissions from fossil fuel drilling and refining have been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular disease, adverse birth outcomes and increased cancer risk. These impacts fall most heavily on Latino and Black residents, who are more likely to live in neighborhoods closest to refineries.

The report also points to the Plastic Pollution Mitigation Fund established under Senate Bill 54 as a potential tool to reduce health harms and prevent plastic-burdened communities from being treated as sacrifice zones.

A sixth-generation Altadena resident presents a community recovery roadmap after the fires Sam James and the Altadena Recovery Team meet survivors’ needs and push for policy-informed advocacy

by Peaches Chung

For Samantha “Sam” James, fire recovery and equitable rebuilding isn’t just a policy debate; it’s the reality of the community she and her family have called home for six generations.

The Eaton Fire destroyed homes across her entire extended family, including part of her own childhood home. James, a first-year master’s candidate in public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, channeled her grief into action, transforming her family’s loss into a blueprint for community-driven advocacy.

It started with one simple text message to a group chat.

“I said I was going to Costco to buy hygiene supplies and asked if anyone wanted to help distribute them,” she said. That small idea turned into a full-scale supply distribution event on her cousin’s front lawn. This sparked a group effort that laid the foundation for the Altadena Recovery Team, which the founders describe as a collective of four Black women who were born and raised in the Altadena and Pasadena area, and now work to restore the spirit of their community.

“We were devastated and feeling helpless,” she said. “Being able to have a place to channel that energy that was productive, and help channel that rage, it was truly healing.”

James co-founded ART, which centers the financial, physical and mental well-being of fire survivors through distribution drives, healing spaces and on-the-ground support. As ART’s CEO, she drives grant and fundraising strategies and ensures the organization’s programs are trauma-informed and community led. Policy conversations with partners at the state level — on issues ranging from rebuilding and long-term displacement support to mental health access — are grounded in her own experience as a community member impacted by the Eaton Fire. Her commitment makes one thing clear: When communities drive their own recovery, healing is possible.

After graduating from UCLA in 2021 with a bachelor’s degree in political science, James came back in 2025 to UCLA’s MPP program with a clear purpose. After completing the highly competitive California Senate Fellowship, where she worked in state Sen. Josh Becker’s office on criminal justice reform, James went on to serve as a community engagement manager for Rising Communities, a nonprofit that works to eliminate disparities in health and social welfare in South Los Angeles. There, she trained the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health on inclusive, trauma-informed community engagement practices and worked on reform initiatives grounded in equity and justice.

“Everything I had learned was on the job,” she said. “I wanted the research background, the theoretical understanding that the MPP offered. Being back on campus has been incredible. I graduated during the pandemic, so returning now and sharing space with my cohort has been deeply meaningful.”

At UCLA, James is also a graduate student researcher with the Black Policy Project in the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies. Her research focuses on whether landlords are following the law and giving formerly incarcerated tenants a fair and lawful screening process. She also serves as the first-year representative for the Public Policy Leadership Association, strengthening student advocacy and community within the program.

She had no idea that a bill she helped draft in Becker’s office would one day directly affect her own family. James helped advance SB 1008, the Keep Families Connected Act, which made phone calls free for incarcerated people and their families. At the time, California’s prison telecom industry was worth $1.4 billion, and more than one in three families were being pushed into debt just to stay connected with incarcerated loved ones.

Years later, now with a family member experiencing incarceration, her own family is benefiting from the policy she helped pass. Seeing that impact up close reinforced her belief in community-centered policy and fueled her decision to pursue her master’s at the Luskin School.

“It was incredible to have that full-circle moment,” she says. “It showed me what’s possible when we push against the systems that keep people down in the incarceration space. It confirmed that criminal justice policy is where I want to be. After Luskin, I want to keep driving that change forward, especially as California continues to lead the way.”

James’ story recently reached a broader audience through TEDxAltadena, where she delivered a message about the unprecedented tragedies that have shaped Gen Z, and the powerful way her generation has transformed that collective rage into action.

“We’ve experienced tragedy after tragedy — 9/11, mass shootings, climate disasters, the pandemic, a mental-health crisis,” she said. “But we’re channeling that frustration into resilience and action.”

Her talk also spotlighted the origins of the Altadena Recovery Team, founded by James, Savannah Bradley, Allison Moore and Makai Ward. Together, they coordinated donations, distributed supplies, started yoga and meditation programs and pushed policy reforms, including support for mortgage relief legislation that Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law in September. They also raised nearly $400,000 through crowdfunding and grants. James framed ART as both a recovery model and a preview of what future climate disasters will demand: localized leadership, shared power, culturally competent support and policy-informed advocacy that ensures longtime residents aren’t pushed out of the neighborhoods they helped build.

“What we know is that climate disasters are only going to intensify,” she said. “We want ART to become a resource for other communities — offering mentorship, seed funding and a roadmap so they can lead their own recovery.”

James’ advice for anyone feeling overwhelmed by the state of the world mirrors the ethos she lives by today.

“Breathe. Take space for yourself. You can only show up for others if you’re showing up for yourself,” she said. “Then get involved. Being on the ground with my community has been profoundly healing. Being in community rarely makes things worse — it almost always makes things better.”

Rooted in her love and care for her community, she is turning her rage, as she puts it, “straight into power.” And she’s just getting started.

Carlos E. Santos Elected President of National Social Work Educators Association Luskin faculty member to lead the Association of Latina/o Social Work Educators

UCLA Luskin Associate Professor of Social Welfare Carlos E. Santos has been elected president of the Association of Latina/o Social Work Educators (ALLSWE), a national organization dedicated to advancing teaching, scholarship, and leadership in social work and social welfare.

“Being elected president of ALLSWE is a profound honor, both personally and professionally,” said Santos. “Personally, it affirms the importance of community, solidarity, and shared purpose among Latin American-origin (LAO) social work educators, especially at a time when many of us, and those in our communities, are navigating significant professional, political, and social challenges. Professionally, it represents a responsibility to steward an organization that has long served as a critical intellectual home for LAO social work educators. I am deeply grateful for the trust placed in me and committed to honoring the legacy of ALLSWE while helping it evolve to meet the needs of our diverse and growing community.”

As president, Santos aims to expand ALLSWE’s reach to educators both within and outside the U.S. and strengthen it as a space of support and community. “I hope ALLSWE remains responsive to the evolving needs of LAO communities, advancing scholarship, teaching, and practice that promote equity, dignity, and collective well-being,” he added.

Santos is widely recognized for his intersectional research on how overlapping systems of oppression shape mental health, educational outcomes, and civic engagement, particularly among queer Latinx youth. His work bridges developmental psychology, social welfare, and public policy, with a strong emphasis on translating research into practice.

Golden Bachelder and Prokriti Monolina: Fellows on the First Budget and Finance Advisory Committee

by Jiah Lee

The L.A. City Council’s Budget and Finance Advisory Committee met for the first time this November with the goal of tackling structural financial issues and shifting towards more long-term budget planning by introducing outside expertise. The creation of this committee was proposed by Los Angeles City Council member Katy Yaroslavsky, who now serves as its chair.

Two UCLA graduate students, Golden Bachelder and Prokriti Monolina, are currently serving as fellows on this committee. Bachelder is a second-year Master of Public Policy (MPP) student and Monolina is a second-year Master of Urban and Regional Planning (MURP) student at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. Bachelder and Monolina are both fellows in the Office of Councilwoman Yaroslavsky.

“It is an honor being able to help with the Budget and Finance Advisory Committee,” said Bachelder. “As one of the graduate student fellows, I am able to work with inspiring Los Angeles leaders and public servants in the effort to put Los Angeles in the best possible fiscal footing. I’m grateful for the opportunity to be able to help a cause that could benefit the city and its people for years to come.”

Monolina also shared her experiences with the committee. “As a UCLA Luskin Leadership Fellow, I am committed to supporting the Budget and Finance Advisory Committee (BFAC) in reimagining Los Angeles’s resources through rigorous policy analysis and targeted research in municipal finance and resource allocation. This work also involves in-depth research in real estate development, land use strategy, and the development of sound financial policy frameworks. It’s an incredible opportunity to work alongside experts and learn from them. One day, I hope to bring these insights to Bangladesh, my motherland,” she said.

Outside of the committee, Bachelder and Monolina continue to make a positive impact on policy reform and the future of their communities. Bachelder served as a fellow in the Office of California Governor Gavin Newsom where he worked to promote shared goals through research on initiatives, and Monolina is a waste researcher who founded an app called Eco360 that promotes green consumerism.

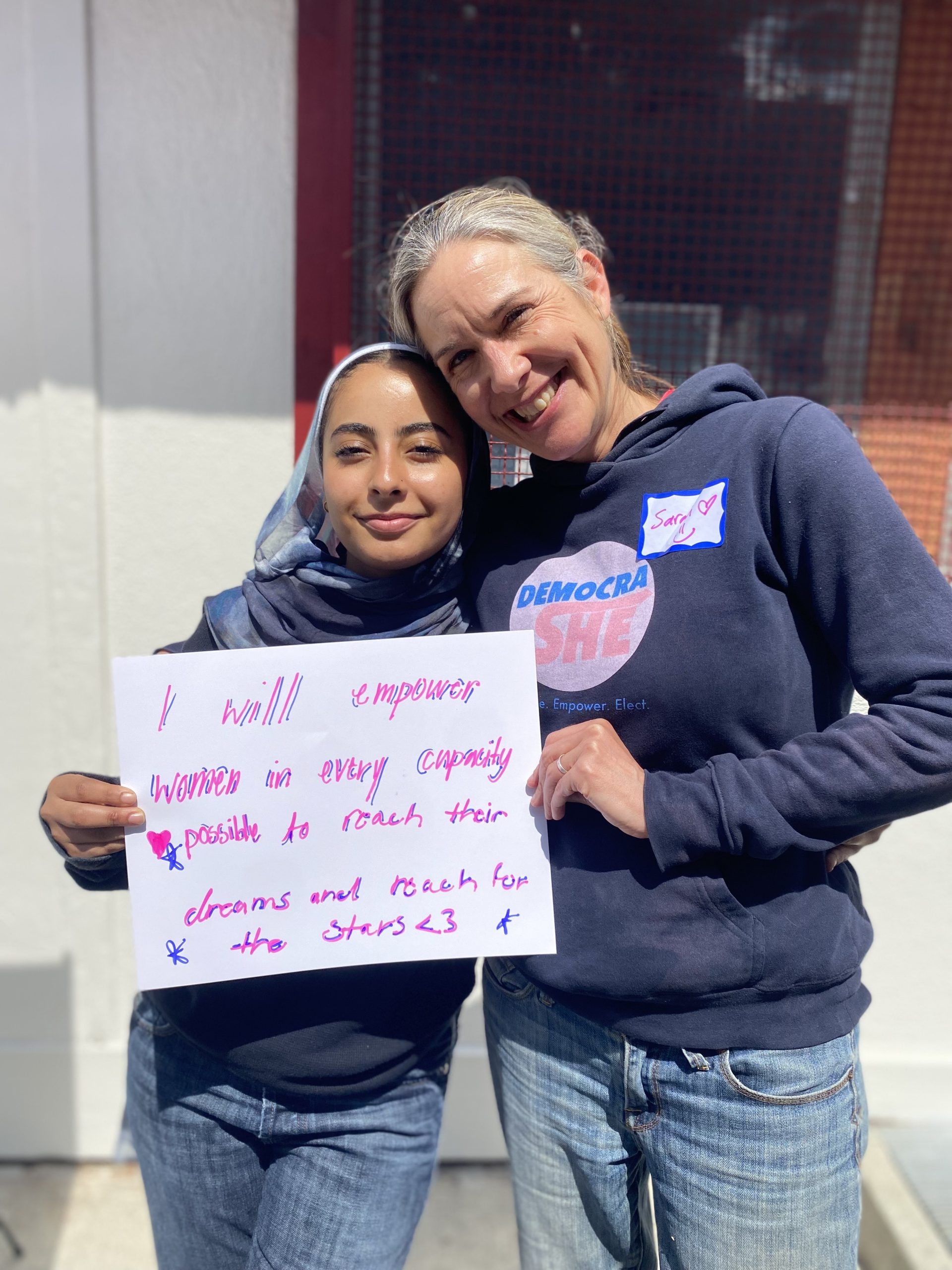

How DemocraShe Builds Civic Engagement for All How UCLA Luskin alumna Sarah Jakle combines trauma-informed practice, public policy, and mentorship to prepare young women for civic leadership.

Sarah Jakle M.P.P. ’04 (she/her) has always believed that leadership must support the whole human being. Her commitment to women’s civic empowerment began long before she founded her organization DemocraShe, but the seeds were planted in the classrooms and mentorship circles she experienced as a graduate student at UCLA.

Jakle studied literature as an undergraduate before beginning her early career working with unhoused communities and individuals living with mental illness. This included an internship at U.S. VETS in Long Beach, where she worked directly with veterans experiencing homelessness, trauma and complex behavioral health needs. The work highlighted the barriers that individuals face when navigating unstable housing, mental health challenges and limited resources.

“I was working with unhoused veterans who had survived extraordinary adversity,” Jakle said. “Trauma was everywhere. It became clear that understanding trauma was essential to understanding how to really help people.”

Although she was making an impact one person at a time, Jakle saw how structural policies often determined whether meaningful change was possible. That realization brought her to graduate school, where she sought to understand the systems that shape people’s lives.

She earned a master’s in public policy from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and later completed a master’s in social work at USC with a concentration in military social work. The dual training created what she describes as a “Venn diagram” of her interests. The public policy curriculum equipped her with analytical and quantitative tools, while her social work training gave her trauma-informed frameworks for understanding the emotional experiences of people navigating public systems.

At UCLA, Jakle took several courses that fundamentally shifted her perspective, including the statistics and evaluation courses that she initially found intimidating as a non-STEM student.

“I was a literature major, so taking calculus-based economics and statistics was a shock,” she said. “But those classes transformed me. They taught me that you cannot assume you have impact. You have to measure it.”

Another defining experience came from her mentorship with former Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, one of her professors at UCLA Luskin. Dukakis invited her to his home, where she met his wife, Kitty Dukakis. Learning about Kitty’s treatment in the press during the 1988 presidential election had a lasting influence on Jakle.

“Kitty was brilliant and compassionate, but she had been deeply mistreated during the campaign,” Jakle said. “It was the first time I truly understood that the emotional experience of being in politics could be as consequential as any policy outcome.”

The experience opened Jakle’s eyes to how women experience public scrutiny, and how often their emotional well-being is overlooked in discussions about civic leadership. This realization stayed with her as she continued her work after graduate school.

From Theory to Practice

Jakle’s graduate training and early career experiences directly shaped the creation of DemocraShe, a nonpartisan leadership program for young women. The organization serves a diverse group of students, with the majority identifying as girls of color and many as first-generation Americans.

DemocraShe teaches students foundational civic knowledge, leadership skills and what Jakle calls “amygdala skills,” which are basic neuroscience tools that help young women regulate fear, discomfort and internalized barriers when stepping into unfamiliar or high-pressure spaces.

“Women are socialized to be perfect, and stepping out of your comfort zone can trigger the amygdala,” Jakle said. “That discomfort often shows up as hesitation or self-doubt, which people call imposter syndrome. We teach girls how to regulate those feelings so they can pursue opportunities that match their ambition.”

Grounding and resourcing are two of the trauma-informed techniques that students learn. Grounding involves returning to the present moment through sensory awareness. Resourcing involves cultivating an inner supportive voice to counteract internalized criticism. Both practices are drawn from trauma research and help to calm the amygdala, allowing the prefrontal cortex to re-engage.

“We teach girls that the brain is constantly scanning for threat and safety,” she said. “If they can regulate the amygdala, they can make choices from a place of confidence and clarity.”

DemocraShe integrates rigorous evaluation into its programming, a discipline Jakle attributes to her training at UCLA Luskin. Students complete anonymous pre-program and post-program surveys so the team can track changes over time. For the full 2025 cohort, 37% of students reported understanding how to move forward as active participants in American democracy before the 10-week flagship program. After completing the program, that figure rose to 99%.

Another key metric asks whether DemocraShe helped students do something they were previously afraid to try; 92% say yes. Examples range from delivering public remarks in religious spaces, to running for school leadership positions, to asserting themselves in instances of workplace conflict.

“These findings tell us that our work is shifting both leadership skills and resilience skills,” Jakle said. “We are helping young women navigate adversity while stepping into the roles they deserve.”

Mentorship and Civic Leadership

Although UCLA shaped her academic foundation, one of Jakle’s most influential mentors came through her political organizing work. She credits Ada Briceño, labor leader and former chair of the Democratic Party of Orange County, as someone who demonstrated what courageous leadership looks like.

“Watching Ada, I saw firsthand how women, especially women of color, experience systemic pushback in civic spaces,” Jakle said. “It made me passionate not only about strengthening our democracy but also about protecting the emotional lives of the women who lead.”

Jakle has also worked as the Get Out the Vote director for the California National Organization for Women. During that time, she heard many women receive vague warnings that political life would be difficult, without being offered any tangible tools to manage the challenges ahead.

“For me, that felt like a missed opportunity,” she said. “We have decades of research on how people can self-regulate during stress. We should not send women into public life without these tools.”

Navigating the Present and Looking Ahead

Jakle believes that civic engagement extends far beyond voting. She encourages students from all academic backgrounds to understand how policy affects their educational pathways, professional fields and daily lives. She also believes that higher education institutions can play a significant role in preparing the next generation of civic leaders.

One of her priorities is advocating for paid opportunities for students to participate in policy work. She notes that many early political pipeline programs are unpaid, which often prevents students who need to work from participating.

“There are meetings happening right now about the future of the UC system,” she said. “Students should be in those rooms, and they should be paid for their time. Otherwise, only students with financial flexibility will get access to those spaces.”

As part of that commitment, DemocraShe pays all participants who take part in its 10-week program or its one-day summer intensives held live on Zoom.

Jakle also recognizes that many young people feel overwhelmed by political uncertainty and social change. She emphasizes the importance of joy as a protective factor for the brain. She teaches a practice called “savoring,” in which individuals spend a few moments each morning noticing two joyful or beautiful things to counter the brain’s negativity bias.

“When there is so much suffering, it can feel like experiencing joy is a betrayal,” she said. “But joy protects the brain. It helps people stay engaged instead of burning out.”

Her advice for those seeking to remain informed and active is simple. She encourages people to find community, participate in local action, and take small, consistent steps that contribute to positive change. She also recommends looking at diverse sources of information and listening to students and young organizers who are at the center of campus activism.

“Democracy is woven through everyday life,” she said. “Small actions matter. Community matters. And every person has a role in shaping the world around them.”

Jakle’s journey from social work to public policy and civic empowerment illustrates how trauma-informed leadership can strengthen democracy. Through DemocraShe, she continues to uplift young women and equip them with tools that support both their public leadership and their inner resilience.

This article was originally published by UCLA Alumni. Read the full article here.

How Rising Debt and Eroding Governance Threaten Long-Term Stability in Five Countries The Berggruen Governance Index reveals a debt-driven cycle undermining long-term stability in five African nations

The Berggruen Governence Index Project (BGI) analyzes the relationship between democratic accountability, state capacity and the provision of public goods. It builds upon prior work that examined the impact of governance and democracy on the quality of life. It is a collaborative project between the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, the Hertie School, and the Berggruen Institute.

The Facts on School Violence: Q&A with UCLA Luskin’s Ron Avi Astor

By Elizabeth Kivowitz

Ron Avi Astor is a professor of social welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs with a joint appointment in the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. His work examines how physical, social-organizational, and cultural contexts in schools relate to different kinds of bullying and school violence. Astor and Rami Benbenishty, professor emeritus at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, have taken input from millions of students, teachers, parents, and administrators, and developed mapping and monitoring procedures that have been used to generate grassroots solutions to safety problems in schools worldwide. Over the past 20 years, findings from these studies have been published in more than 200 scholarly manuscripts.

Astor’s work has been funded by the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Mental Health, and other public and private foundations.

We caught up with Astor to gain a better understanding of school violence — and how to create safe schools.

Is school violence getting worse — and why does it happen more in the U.S.?

Overall, day-to-day school victimization, including physical, verbal and social exclusion — has declined significantly in recent decades across the United States. In contrast, behaviors involving cyberbullying through phones and the internet are on the rise. When it comes to shootings and deaths, however, the situation has worsened. The increasing frequency of shootings, intense media coverage, and widespread use of hardening measures in schools contribute to the perception that all forms of violence are escalating.

This is why it is essential to distinguish different types of victimization. School shootings are a separate phenomenon, more akin to terrorism, and should be considered independently from everyday violence. Cyberbullying is another category that requires its own focus, as it is increasing.

For day-to-day school violence, the United States is not among the most violent countries; many nations have had far higher rates for decades. But when it comes to school shootings and deaths from shootings, the U.S. is by far the highest globally and accounts for a large proportion of such fatalities worldwide.

Are there any recent lessons we are not talking about that we should be?

Yes. One major lesson is the dramatic reduction in day-to-day victimization in schools over the past two decades, a fact overshadowed by the trauma and visibility of school shootings. While shootings must be addressed urgently, these reductions mean that millions of students are no longer experiencing the same levels of victimization reported 20 years ago. This progress is often overlooked, as are the tremendous investments in programs, hiring of social workers, psychologists and counselors, and the expanded district and state safety infrastructure now in place.

Teachers, principals, and communities have made bullying and school safety a priority, and their combined efforts appear to have worked. The United States has invested billions of dollars in social-emotional learning, positive school-climate initiatives, anti-bullying programs, trained staff, and new safety policies — all likely contributors to the decline. The belief that “nothing works” to reduce school violence is incorrect, particularly for day-to-day victimization. Educators, parents, communities, and students deserve recognition. This is also why separating school shootings from less lethal forms of school violence is so important.

What is the most important thing a school can do to create a positive school climate?

After studying thousands of schools around the world, I have found that the most influential factor, across cultures, is the principal’s vision, skill, and mission. An effective principal who emphasizes both academic excellence and the social role of schools is the key to reducing violence. These exceptional leaders unify staff, students, and communities around a shared vision of safety and foster environments that are welcoming, caring, and supportive.

They integrate ideas from students, staff, and families, while also selecting evidence-based programs adapted to their school’s specific needs. One important implication is the need to include school safety content in principal and teacher training programs, as most universities currently offer little or no preparation in this area. Studying talented principals and educators who successfully create caring, safe schools is another area requiring more research. While evidence-based programs matter, there is much to learn from the people who implement them effectively.

What are schools doing to improve safety?

Recent studies show that schools are using a wide range of strategies to improve safety. These include evidence-based programs such as social-emotional learning, restorative justice, school-climate initiatives, anti-bullying programs, and systemic efforts like PBIS (positive behavioral interventions and supports) and MTSS (multi-tiered system of supports). Schools are also increasing capacity by hiring more social workers, psychologists, and counselors to support these programs and address mental health needs.

At the same time, many schools rely on law-enforcement approaches related to school shootings: shooter drills, lockdown practices, and employing school resource officers or police. Schools are also “hardening” their campuses with metal detectors, cameras, high-tech shooter-detection systems, and strict safety policies. In some states and districts, school staff are now permitted to carry firearms. These developments largely stem from the ongoing failure to reduce school shootings.

Please explain the difference between voices and data in your work and why it matters for keeping students and schools safe.

The core of creating a successful school action plan is closely listening to the voices of students, teachers, parents, and the community. Without this, most programs and strategies fail. In many schools, only a small number of people openly express concerns, even though school communities hold diverse views about safety. In the intervention programs I developed with my colleague Rami Benbenishty, we begin with students’ voices. Students create qualitative maps of the school and describe times and spaces where they feel safe or unsafe, explain why, and offer recommendations for making unsafe areas more welcoming. We do the same with teachers and parents. We also conduct short surveys with quantitative and qualitative questions. These anonymous results are presented back to the school and become the basis for discussion and action planning.

People often disengage when they hear the word “data,” seeing it as distant. I challenge educators to imagine each response as a child’s voice about safety, drug use, suicidal ideation, or ideas for improving school. When seen as collective voices, the information becomes personal and encourages engagement. We frequently observe teachers shifting their practices when they realize many students — through surveys and maps — are struggling with mental health issues, substance use, or victimization. At that point, it is no longer data but a message from students, teachers, and parents. These voices and recommendations become the foundation for meaningful grassroots change.