Panel Highlights Growing Presence of Women in Military Speakers at Luskin’s annual Veterans Day seminar explore the role, challenges and accomplishments of women in the armed services

By Zev Hurwitz

Two U.S. military veterans and a photojournalist who has made it her mission to bring female veterans’ stories front and center spoke Nov. 10 at the third annual Veterans Day seminar at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

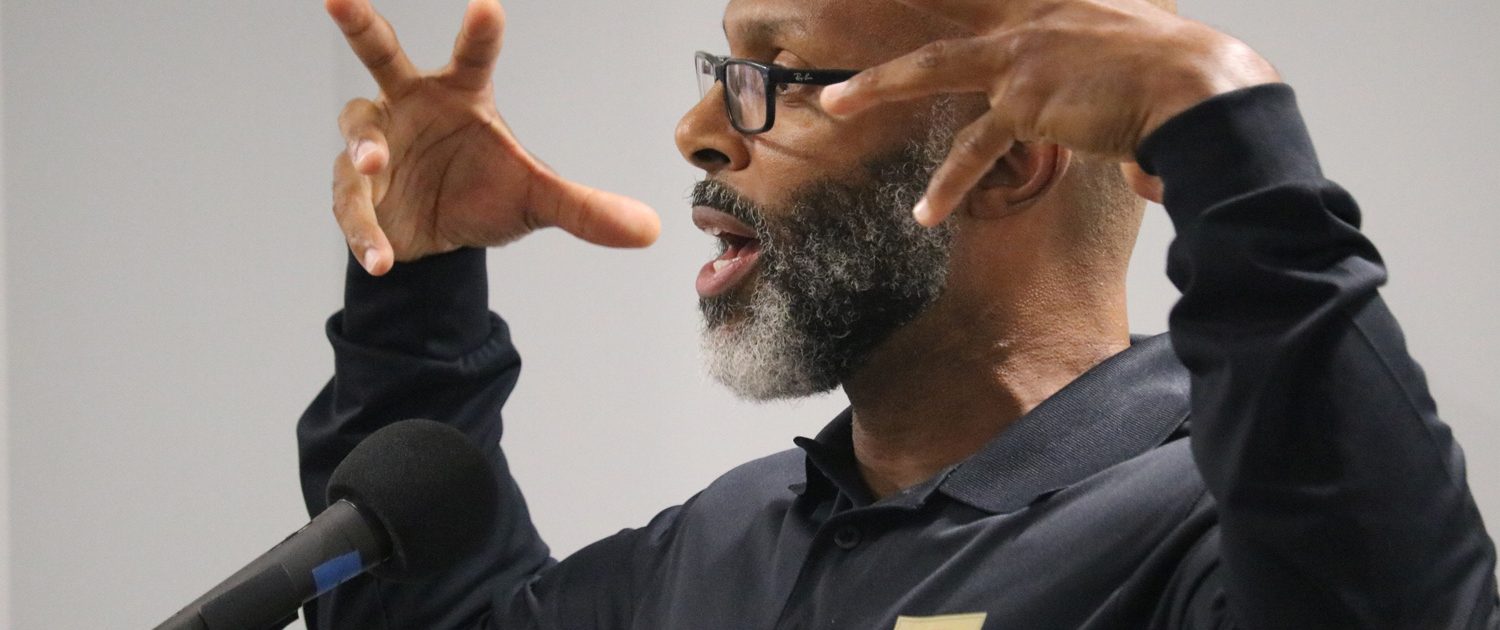

“Women Who Serve,” hosted by the California National Guard, UCLA Luskin Department of Social Welfare, UCLA Nathanson Family Resilience Center and U.S. Vets, began with an overview of women in the armed services presented by emcee Kathleen West, who holds a Dr.P.H. degree from UCLA and is a lecturer on military social work at the Luskin School.

West said that women make up more than 15 percent of active duty military members in the U.S., including 18 and 19 percent of the Navy and Air Force, respectively — a dramatic increase since the Vietnam War, when just 3 percent of the military was female. She noted, however, that only about 10 percent of veterans currently living in the U.S. are women.

“That is a real challenge, because when they leave the service, we don’t have the [Veterans’] services in place for them that we need to,” West said. “That is one thing we want to talk about right now: What is our present looking like and what do we need to be thinking about for the future?”

West noted that the Department of Defense aims to achieve gender parity in the military by 2030 and said that there has been progress in allowances for parental leave for active duty members, although more work is needed to fully realize women’s military rights.

Therese Hughes MA UP ’99, one of the event’s panelists, spoke about her motivation for spending much of the past six years as a photojournalist, documenting the stories and images of female veterans and active duty military personnel.

“History is critical for civil engagement and for public policy, and when properly taught, it teaches the pursuit of truth and understanding,” she said. “Women’s stories in history are critical. Women’s stories in the military are essential.”

Hughes, who launched her traveling exhibit/photojournalism book “Military Women: WWII to Present Project” in 2010, says she has interviewed more than 800 women and ultimately plans to reach 1,200.

During the Luskin panel, Hughes also highlighted unique groups of female veterans that she has interviewed for the project. They include immigrant women who elected to serve as a way to give back to the country that welcomed them, as well as the pioneers of modern female military service: veterans of World War II.

“I’ve interviewed 68 of them,” she said of the World War II veterans. “I have five that are alive today. It breaks my heart every time I hear of one who has died, because these women were the footprints, the foundation of the women who serve today.”

Col. Susan I. Pangelinan, an active duty National Guardsman and former Air Force reserve member, spoke about women’s military service through the ages, framing the developments through her family members’ experiences in the military over the past several decades. Pangelinan talked about obstacles that women have faced in the journey toward equality, noting a 2013 landmark policy change that allowed women to serve in combat roles. Additionally, women are now finding role models in divisions of the service historically dominated by men, such as maintenance.

“We have female leaders in abundance that we hadn’t seen before,” she said. “Women are seeing other women just like them rising to very high places and high levels of responsibility.”

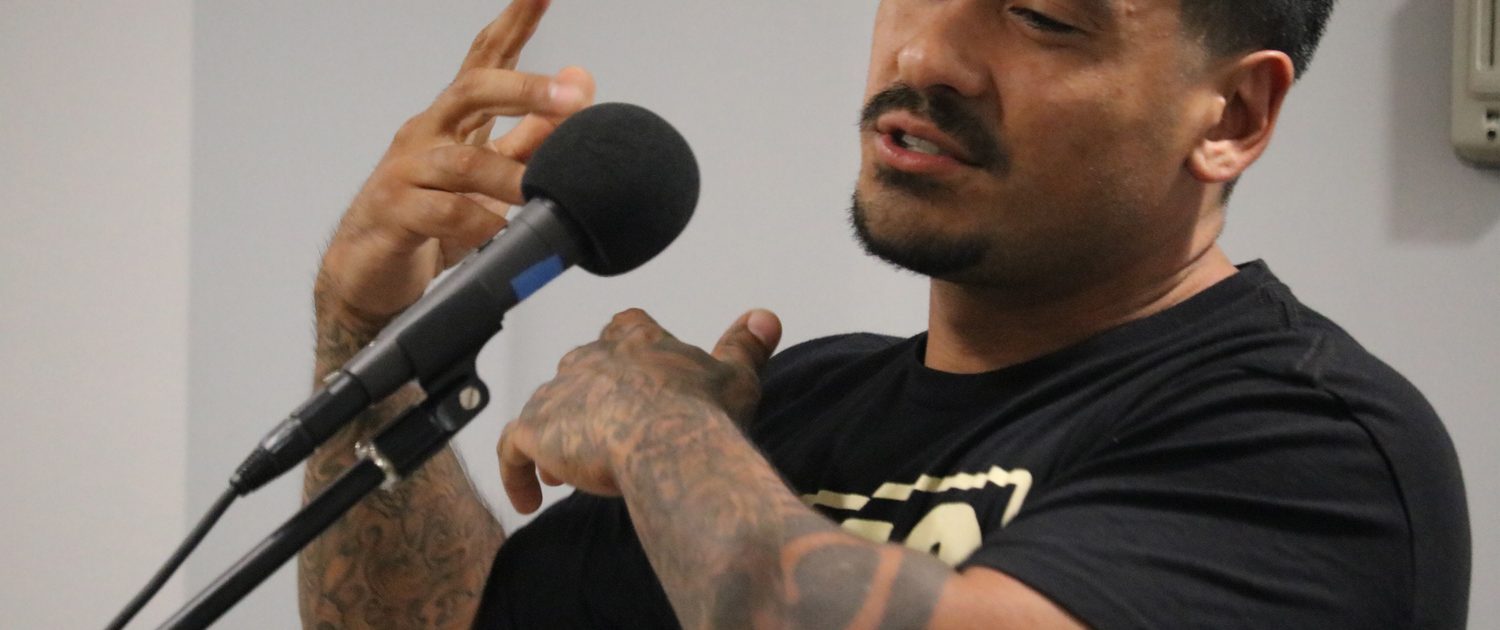

Megan Rodriguez, a U.S. Air Force veteran and current district representative for state Sen. Carol Liu, spoke about the darker side of military service. Rodriguez told of her personal challenges in the service. During the year-and-a-half that she served in the Air Force, Rodriguez was the victim of a sexual assault, which had lasting effects on her physical and mental health.

Rodriguez, who had only publicly spoken twice before about her experience as a victim of Military Sexual Trauma (MST), stressed the importance to her of sharing her experiences to broad audiences.

“The reason I’m able to speak about it is because I know there are other women veterans and nonveterans who have gone through the same thing,” she said. “Providing this place for discussion is essential, and I want to provide a safe space to other women and men that go through this.”

Laura Alongi, a field faculty member in the Luskin Department of Social Welfare, introduced the evening and said the yearly event was aimed, in part, to further the department’s work with veterans.

“Part of the reason we do this, is because as a department … we started to realize a few years ago that meeting veterans’ needs is something we really wanted to do,” she explained. “We felt that, because of our focus, we could really provide services and trainers who provide those services in a holistic way to veterans and active duty military.”

While economic downturns have been linked previously to increased suicide risk in the United States, new research from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs sheds light on the role alcohol use may play in the complex relationship between economic conditions and suicide.

While economic downturns have been linked previously to increased suicide risk in the United States, new research from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs sheds light on the role alcohol use may play in the complex relationship between economic conditions and suicide.