UCLA School of Public Affairs Among Charles E. Young’s Lasting Legacies Former colleagues recall the late chancellor and his role in the 1994 consolidation of degree programs

By Stan Paul

Charles E. Young, the former UCLA chancellor who passed away Sunday at his home in Sonoma, California, at age 91, was instrumental in the creation of what later became the Luskin School of Public Affairs.

During a time of budgetary constraints, the long-established schools of Social Welfare and Urban Planning were combined in 1994 with a new graduate department — Public Policy — in one new school. In recognizing Young’s legacy and significance at UCLA Luskin, Interim Dean Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris said it was his vision that made today’s Luskin School possible.

And, as she wrote to the UCLA Luskin community, “placing his faculty appointment in our Public Policy department, he immediately elevated the visibility of our School in its very early days.” Loukaitou-Sideris noted that Young always kept a great interest in “his school” long after his official retirement. “As late as June 25, 2023, he emailed me to express his pleasure and congratulations for Urban Planning having been ranked as No. 1 in the nation.”

Several others who knew Young and his relationship with UCLA Luskin offered their remembrances.

Daniel J.B. Mitchell, professor emeritus of management and public policy, was on the faculty at UCLA at the time of the transition. He said Young supported the final result, but the original idea was different.

“Originally, the idea was to create an interdisciplinary research center — not a school — for faculty with a general interest in public policy,” recalled Mitchell, who served as chair of public policy from 1996 to 1997.

In the aftermath of the 1992 civil unrest in Los Angeles following the Rodney King verdict, and in response to budgetary pressures coming from the state that would require rethinking some programs at UCLA, Young appointed a committee to take on the task. It was headed by Archie Kleingartner, professor emeritus of management and public policy, who would become the School’s founding dean.

“Young expanded the task to include creation of a full school of public affairs. He felt that public policy, particularly aimed at state and local concerns, should have a distinct presence at UCLA, both for research and for the production of professionals in the field,” Mitchell said.

Kleingartner said Young had reached the conclusion in the early 1990s that UCLA could and should do much more in the field of public policy. As a premier university, UCLA had an obligation to provide research and teaching at a high level in public policy, said Kleingartner, noting that although Young’s master’s and doctoral degrees from UCLA were in political science, his personal academic research interest was in public policy.

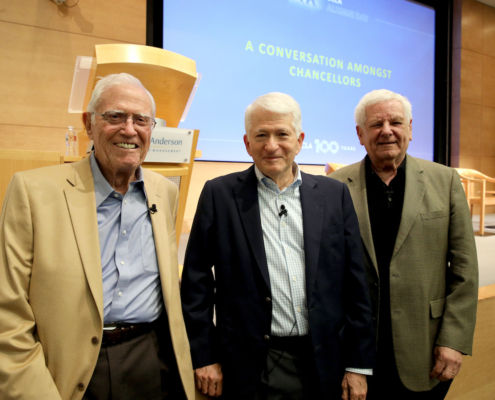

Young with current Chancellor Gene Block and former Chancellor Al Carnesale.

After the decision on a new public affairs school was reached, top-level attention turned to how to go about creating a public policy entity and what it should look like, Kleingartner said. “The chancellor was interested in something big and impactful.”

A second strategic decision was based on the fact “that very little by way of new funding would be available, that the main resources would have to be found from within the university,” he said. “So, a really big issue was to reorganize in a way that generated savings.”

Kleingartner said the late Andrea Rich headed up the administrative and financial aspects of the restructuring, and he led the academic and faculty aspects.

“But many faculty and administrators got involved because it was quite a complex undertaking,” he said.

At that time, a number of schools and institutes were reorganized as part of the Professional School Restructuring Initiative, or PSRI, and it was done amid a great deal of internal opposition from existing schools, institutes and their faculties. But “the chancellor remained firm despite the extensive opposition.”

The School — with a different name but in essentially its current form — was officially launched on July 1, 1994. That wouldn’t have happened without Charles E. Young, and “I think at this point, most people are quite satisfied with what was created,” Kleingartner said.

Zev Yaroslavsky, director of the Los Angeles Initiative at the Luskin School, has known Young since Yaroslavsky’s days as an undergraduate in the late 1960s. That association continued during his career as a Los Angeles City Council member and Los Angeles County supervisor representing districts including the Westwood campus.

At a time of declining state support for higher education, Yaroslavsky pointed out that Young “saw what was coming” and took steps to help UCLA remain competitive as a top public university, according to a story posted by UCLA Newsroom.

“Chuck was a bold and visionary leader who catapulted UCLA to one of the world’s great research universities,” Yaroslavsky commented. “Moreover, under his stewardship this university became a consequential player in its own backyard — Westwood and the greater Los Angeles community. As an elected official who represented UCLA for four decades, I never had a better partner.”

Stewardship and partnerships were a hallmark of his work and affiliations on campus.

“Chancellor Young welcomed me personally when I was recruited to UCLA,” said Fernando Torres-Gil, professor emeritus of social welfare and public policy. He recalled Young’s graciousness and interest in his career, which would include a number of leadership roles at UCLA Luskin.

“Since that time, I took great joy in calling him ‘Chuck’ and experiencing the great university he helped to create. Very few individuals have the good fortune to see a legacy grow and flower, and Chancellor Young could enjoy his creation on his many visits to campus post-retirement,” Torres-Gil said.

Read more about the life and career of the former chancellor on UCLA Newsroom.