By Elizabeth Kivowitz

With recent indictment charges against New York City’s mayor and the media focused on the presidential election, it’s easy to forget Los Angeles City Hall was rocked by scandal two years ago when a secret recording of City Council members discussing redistricting exposed racism and corruption at City Hall. The city and county also continue to have the largest numbers of unhoused people in the nation.

To try to address some of these challenges, Angelenos are being asked to vote on a number of ballot measures and charter amendments.

UCLA convened a panel of experts on local ballot measures in Los Angeles County (video) to shed some light on these efforts to create greater transparency, better governance and improved quality of life in the nation’s second largest city — specifically Measures A and G and Charter Amendments DD, LL and ER.

Some excerpts:

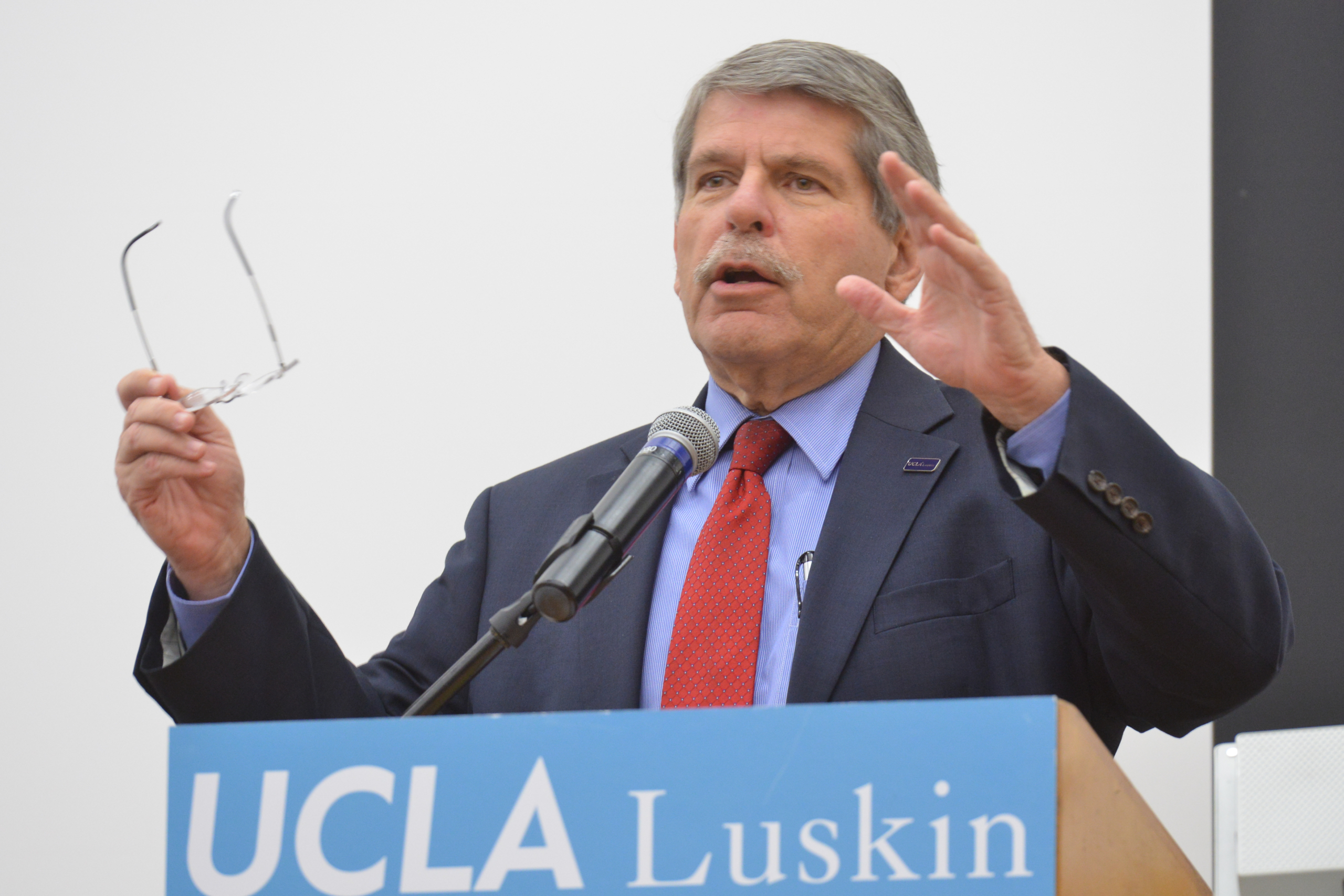

Gary Segura, professor of public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, co-chaired the L.A. Governance Reform Project, a coalition of scholars and researchers who developed proposals for bringing better governance to L.A.’s halls of power. Segura spoke about Charter Amendment DD, LL and ER, which would create independent redistricting commissions for seats on the City Council (DD) and L.A. Unified School District Board (LL) and strengthen the city’s ethics commission (ER). Segura says:

“I think there was a sense that ethics and governance in Los Angeles had reached a point where there were more embarrassments than the city could reasonably continue to endure. … So after the recording was released, there was a sense, in a variety of corners in the county, in the city and in civil society, that something had to be done.”

“The independent redistricting commission [for the City Council] that we will vote on doesn’t take effect until after the 2030 census. … So those somewhat illegitimate seats are going to continue until 2032. That’ll be the first time to change it. Both L.A. city and county are 48% Latino. The city has 33% Latino representation, and the county is even lower. So that’s the background here. And the city, I think, didn’t act in good faith, so much so that the attorney general of California, Rob Bonta, is investigating to see if he can bring a case against the city to force them to redistrict sooner than the 2032 election.”

“You’ll hear talk of charter reform, and this is a classic example. Whenever a public body doesn’t wish to put specific reforms on the ballot, you create a charter reform commission because it kicks the entire thing down the road and offloads responsibility.”

Zev Yaroslavsky, executive director of the Los Angeles Initiative at UCLA Luskin, served on the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for 20 years and on the Los Angeles City Council for nearly 20 years before that. He offered insight on Measure G, a governance measure that would expand the number of county supervisors from five to nine and create an elected executive. He cited decades of failure of the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, the county’s largest, before it was temporarily shut down in 2007 by the federal government, as well as accountability and decision-making during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, as proof that the county needs an elected executive:

“There was no risk to us politically, no existential risk that if the hospital shut down that we would somehow lose our election, because there was no one person who was politically accountable to the people of L.A. County. No mayor would have allowed that to go on for 30 years with incompetence. No business would run that way. No state would run that way. Our country doesn’t run that way.”

“You had five supervisors who had five different shades of opinion about what to do in response to the pandemic. None of them have a medical degree or a public health degree. As I’ve said many times … you can negotiate with the Board of Supervisors. You can’t negotiate with the COVID-19 virus that has a mind of its own, and we got away with a lot, but we had a lot of people die. We would have a lot more people die if [Los Angeles County Department of Public Health Director] Barbara Ferrer didn’t have a backbone and was willing to use her credibility with the board. But that’s not the way it should work. She should be accountable to the mayor of the county, to the chief executive, and not negotiate about it. Let the science dictate what needs to be done.”

Michael Lens, UCLA Luskin professor of urban planning and public policy, acknowledged that voters are concerned that prior measures have not solved homelessness.

“While the existing 1/4 cent sales tax, Measure H, has funneled billions of dollars into homelessness services and housing, we can’t be sure that Measure A, a 1/2 cent sales tax, in perpetuity, will solve it either. But we do know that there is an extreme need, and that’s the trade-off that voters face.”