By Les Dunseith

When the “parking cash-out program” became law in California, Donald Shoup had done it! Surely, this would launch a wave of legislation to reform all those nonsensical parking regulations he’d been writing about since the 1970s.

Or so it seemed in 1992.

Shoup’s idea was that any employer that offers subsidized parking for its workers should also offer employees the option of taking the cash value if they opt out of parking. Within a year of getting the attention of a state assemblyman, it was passed by the legislature and signed by the governor.

“And I thought, well, this is easy! I just have to be clear and explain what I’m doing,” Shoup recalled. “But [parking reform] has taken a very long time to really sink in.”

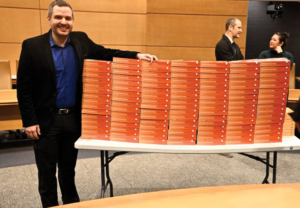

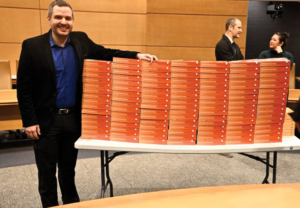

Planning Commission official Chris Meyer stands with a huge stack of Don Shoup’s book “The High Cost of Free Parking” weighing down a folding table during a news conference in Minnesota that was held to launch a parking reform effort in the state. The books were distributed to all members of the Legislature.

To understand Shoup’s research on parking, it helps to have read his landmark book with the wry title: “The High Cost of Free Parking,” first published in 2005. But it’s not required. Don Shoup is adept at boiling his crusade down to four key reforms:

1. Parking cash-out.

2. Eliminate requirements that force real estate developers to accommodate a minimum number of parking spaces per construction project, a practice that Shoup viewed almost as “an established religion” in the planning profession.

3. Charge drivers for parking on city streets and in city lots, setting the price to ensure one or two open spaces on every block.

4. Make the practice of paying for parking politically popular by dedicating the revenue to additional public services. “So, if anybody puts a dollar in a parking meter, it comes right out the other side to clean the sidewalk or repair the street or plant trees,” Shoup explained.

Shoup sees previous parking practices as a flimsy house of cards. “They were assembled over decades by officials who were arbitrarily adding a parking requirement,” he said. “And it was all a pseudoscience.”

Decades later, the wave of policy change Shoup always envisioned may finally be arriving. A spry octogenarian who still comes to campus regularly almost a decade after retiring, the distinguished research professor of urban planning is seeing his ideas being implemented in city halls, statehouses and government offices far and wide:

- Buffalo, San Francisco and San Diego are among numerous cities that have rethought parking policies.

- Two years ago, California abolished parking minimums within a half-mile of transit. Other states are looking to do the same. And a bill introduced in Congress could take the idea nationwide.

- Dynamically priced curb parking continues to spread at the municipal level, and the federal government has spent millions looking into the practice.

- Several international locales have acted on Shoup’s ideas or studied their feasibility.

A central focus for Shoup is the practice of devoting immense amounts of valuable land primarily to free parking for cars. It’s all those places where cars sit, unmoving, 95% of the time. Surely, everyone can understand that having too many cars contributes to exhaust-filled, unwalkable cities plagued by traffic jams? We know about carbon emissions and how automobiles contribute to climate change, right?

Professor Michael Manville is one of Shoup’s former students and now chair of Urban Planning at UCLA Luskin. He wrote an essay for the Journal of Planning Education and Research in 2022 that extols Shoup’s vision:

“Transformation requires reform, reform requires action, and actions can’t be ambiguous. Actions are clear and specific — what exactly should we do?

“Don Shoup is clear and specific: Price the curb. Abolish the parking requirements. Invest in the neighborhoods.”

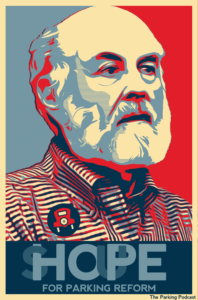

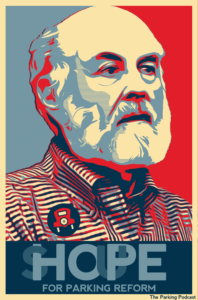

Isaiah Mouw hosts The Parking Podcast, and Shoup was a guest. So, Mouw had a friend create artwork that the professor has since adopted as his signature image on social media. It shows Shoup’s face in a style made famous by artist Shepard Fairey. Mouw said, “I saw the Obama ‘Hope’ poster and thought parking reform could use a ‘Shoup’ poster.

Among Shoup’s followers are government officials and planning consultants, plus environmentally conscious cyclists and fans of public transit. Shoup’s observations can be an epiphany for many people. Some become devotees. They call themselves “Shoupistas.”

Patrick Siegman was the first.

He never took a class from Shoup. He never even took a class at UCLA. Siegman discovered Shoup’s research while an undergraduate at Stanford. And that discovery has had more influence on his life and career than anything in a class he did attend.

“Professor Shoup managed to make the apparently dry topic of parking economics and regulation not only worth studying, but compelling, fascinating and, at times, hilarious,” Siegman wrote in an essay for Streetsblog.

How did Siegman become the original Shoupista?

“I was at a beer garden here in San Francisco,” Siegman said in an interview. He had just finished an outing with friends. It was sometime in the 1990s.

“We’re hanging out and talking — a whole bunch of bicycle advocates — and I started yammering away about my thoughts, and Shoup’s research and the importance of parking reform. I’m with Dave Snyder, who was the executive director of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, which has a lot of your classic San Francisco radicals. He just looked at me and said, ‘Man, you’re just a Shoupista!’” Siegman remembers it getting a big laugh. He and his friends got the reference immediately because they’d grown up during the 1980s when revolutionaries were taking on right-wing dictatorships across Latin America. In Nicaragua, the rebels were known as Sandinistas.

What’s it like being the first Shoupista?

“Well, it’s an honor,” Siegman said. “It also surprised and delighted me how that term took off. It has taken on a life of its own.”

Siegman was the first of many. Kevin Holliday was enlightened by Shoup’s ideas while pursuing the MA UP degree he earned at UCLA in 2014. Four years later, he formed a Facebook group, The Shoupistas, for “the followers of Professor Donald Shoup.” It now has more than 8,000 members.

“Today, there is still a lot of traffic on that group,” Holliday said. “People are obviously interested in it.”

Holliday spent about 18 years working as a planning professional, then more recently started his own company, Bright Triangle, which provides process improvement consulting services.

He was involved in implementing pricing for parking based on demand in San Francisco, which saw roughly half of its meter prices decline.

People who wind up focused on parking reform arrive unexpectedly, he said. “No one grows up thinking they’re going to work in parking.”

Shoup himself came to parking reform by surprise, and that’s part of his legacy, Holliday said. Shoup’s dogged determination is also a marvel to Holliday: “How many other people in this world can get folks to read an 800-page book?”

The Parking Reform Network tracks the progress of policy changes on an interactive map. For five years, the network has been educating the public about Shoup’s work, and President Tony Jordan says their database is increasingly a go-to resource for people wanting to make parking changes a reality.

So far, the parking reforms have taken hold mostly in left-leaning places. But Shoup and others don’t see the issue as being conservative or progressive. Both the Obama and Trump administrations came out in opposition to minimum parking requirements.

“Getting rid of parking requirements appeals to the right because it gets the government out of business,” Shoup said. Not having to provide a fixed amount of parking makes life easier for housing developers, reducing their costs.

“So, you can imagine why Trump … he’s a developer. He knows what parking requirements demand. He thinks he should be in charge of how many parking spaces he provides!” Shoup said with a chuckle.

“Getting rid of parking requirements appeals to the left because it reduces traffic congestion, air pollution and carbon emissions. It can be part of the war on cars,” he said.

Shoup himself is purposefully nonpolitical. “I recommend parking reforms that will benefit almost everyone regardless of their politics.”

One reason that Shoup’s ideas have taken hold and spread is that his writing is very clear. Manville and Holliday are among the many students and colleagues who’ve assisted him over the years and continue to do so as co-writers and editors. They see Shoup’s approach as different from most professors.

“There’s a model of academia that says you must publish lots of articles, and every few years the dean counts up those articles and you get a raise,” Manville said. “And so you sort of do the minimum to get it published, and then you move on to something else.

“He always wrote, and still does write, articles with a mindset of not just getting them published in academic journals, but also to be available to anyone who cares to read them,” said Manville, noting that Shoup strives to write in a manner that will appeal to students.

“He always had a very good understanding that one of the most powerful things you could do from a policy perspective is have a publication end up on someone’s syllabus,” Manville explained. “Because then the future planners of the world have no choice but to read it.”

Donald Shoup holds his hands close together to show the actual size of the statue in a photo enlargement that fills one wall of his office. Photo by Les Dunseith

Shoup embraces every means that will spread the word. He’s active on social media. Interviews with him can be found on YouTube and TikTok. And as an in-person marketer of parking reform, he is relentless.

“Anywhere he goes, he’s going to grab somebody and start talking about parking,” Manville said. He recounts a story of Shoup discovering on a flight to Sacramento that a member of the Assembly was a few rows ahead.

“And he connived to switch seats with the person next to that guy, and then just harangued the poor man about parking on the whole flight,” Manville said. “That’s Shoup in a nutshell.”

Shoup tends to downplay his accomplishments, citing luck and longevity. He notes that he first used the word “parking” in an academic article in 1970 and began focusing on the reforms in earnest in 1978.

“THAT is perseverance,” he said.

Shoup also credits the support he received at UCLA and the freedom he felt within Urban Planning to keep saying what he believed even when others dismissed it.

Most people would have tired of the crusade long before 40-plus years. Not Donald Shoup.

“He just keeps going and going and going,” Holliday said. “And I think that’s a testament to not only how deeply he believes these things, but how much he wants to convince someone else to believe them.”