How Laws and Policies Can Close — or Widen — Gender Gaps New book by UCLA researchers shows that progress toward gender equality has stalled, particularly for caregivers in the U.S.

By Les Dunseith

A comprehensive review of economic gender equality in 193 countries by the UCLA WORLD Policy Analysis Center identifies global trends and exposes policy gaps that include shortcomings when it comes to caregiving.

When the authors of a new open-access book first began tracking maternity leave policies around the world in 2000, they were alarmed to find that 18 countries had no national paid leave in place for working mothers. Today, seven remaining countries still lack such protection — five small island nations, Papua New Guinea, and the United States of America.

The book, “Equality within Our Lifetimes,” pulls together information from more than a decade of research that has also been collected into a robust, freely downloadable database. Co-author Jody Heymann, a professor at UCLA and founding director of WORLD, said that through the 1980s gender equality was rapidly advancing.

“There were more women entering the workforce. There were increased economic opportunities for women, increased educational opportunities,” she said. “That progress has completely stalled.”

The country’s gender wage gap has barely budged for 15 years. What’s more, it’s even broader among parents. In 2021, the average mother working full-time in the U.S. still earned just 73 cents for each dollar earned by a father working full-time.

Because U.S. women remain predominantly responsible for all types of caregiving, it’s not just new mothers who are impacted by the continued lack of federal paid family leave and other legal protections for caregivers in the workplace. The authors cite studies that show women are three times as likely as men in the U.S. to lose their jobs or to leave the workforce because they’re caring for an ill adult.

The economy has felt the impacts. From 2000 to 2019, the U.S. dropped from 7th to 23rd in a ranking of 36 high-income countries on women’s participation in the labor market, Heymann noted. Amid COVID-19, women’s labor force participation fell to its lowest rate since 1987 and has yet to fully recover — with Black and Latina women experiencing the greatest losses.

Heymann and her research team analyzed national laws and policies in all 193 countries of the United Nations. Among their findings:

Heymann and her research team analyzed national laws and policies in all 193 countries of the United Nations. Among their findings:

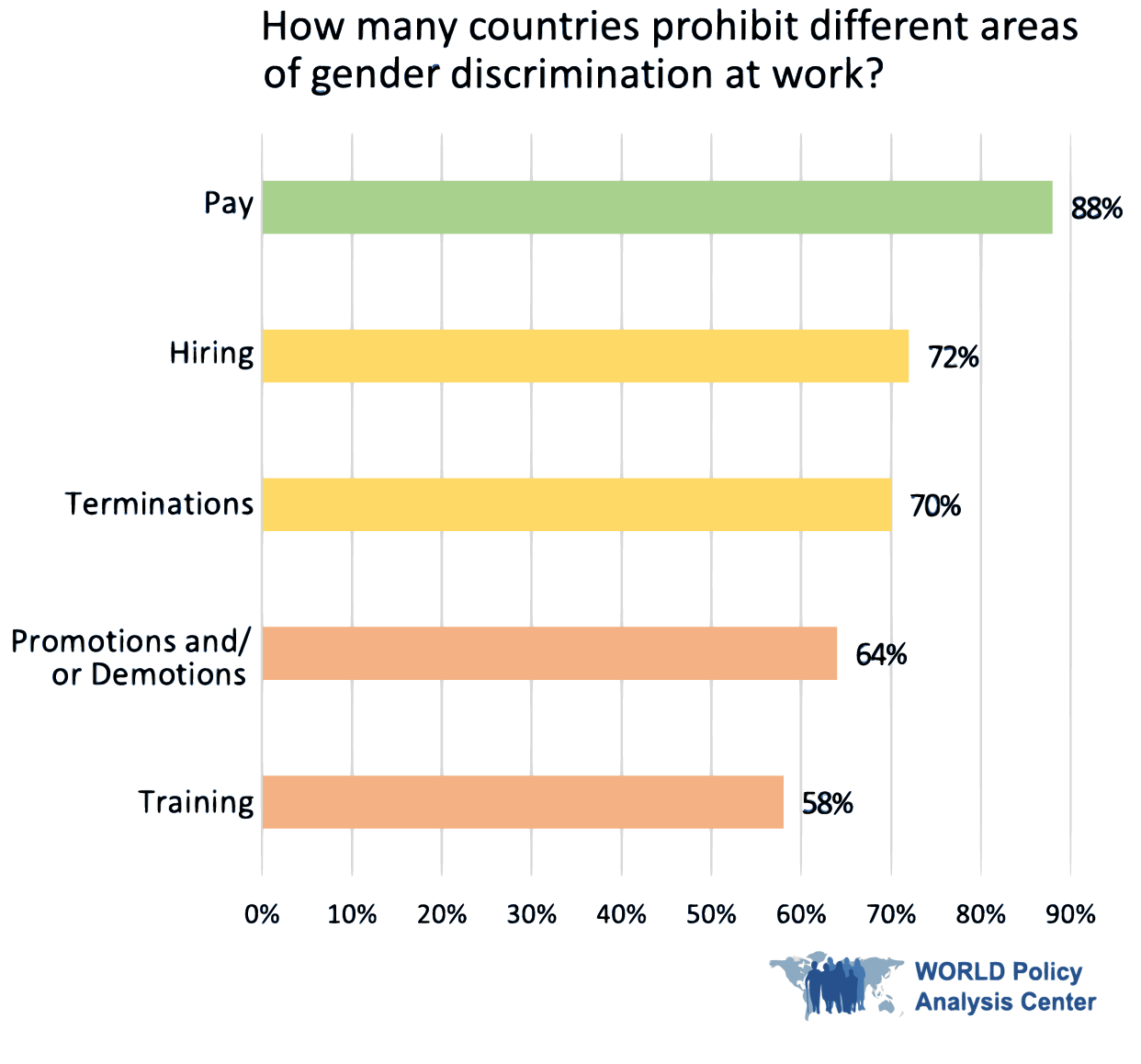

- Although nearly all countries (93%) now prohibit at least some form of gender discrimination in the workplace, only half prohibit discrimination based on family responsibilities.

- In 1 in 5 countries, employers can legally discriminate against women of color because laws fail to prohibit employment discrimination based on both gender and race.

- Over five years since #MeToo went global, 1 in 4 countries still fail to explicitly prohibit sexual harassment at work. In about one-third of countries, the law is silent on employer retaliation, meaning women can be fired if they report harassment.

- Two- thirds of countries fail to provide paid leave to care for a child during routine illnesses or to take them to the doctor.

- A majority of countries (58%) provide no paid leave to care for an ill spouse, and 61% offer no paid leave to care for an aging parent.

Fathers of infants have far less paid leave available to them than do mothers.

More encouraging for the authors is a worldwide trend toward paid leave for new fathers. Between 1995 and 2022, 71 countries enacted paid leave for dads, increasing the share of countries globally with leave from 24% to 63%. The U.S is not among them.

In the United States, some private employers and 11 states, including California, now offer paid parental leave, although inconsistently. Co-author Aleta Sprague, an attorney and senior legal analyst at WORLD, said the negative impact of not providing paid family leave at the national level is far-reaching.

“It’s no longer in question that our lack of support for new parents and other caregivers is driving women to leave the labor force,” Sprague said. “And that in turn is a barrier to economic growth.”

UC Press is releasing the book — authored by Heymann, Sprague, and co-author Amy Raub, principal research analyst at WORLD — at roughly the halfway point of the Sustainable Development Goals, a 2015 United Nations commitment to ensure equal rights across the globe by 2030. It is being distributed online, accompanied by briefing papers and downloadable assets in multiple languages, as part of a commitment to making top university research readily available to everybody, Heymann said.

The book presents new research on the extent and pace of policy change in 193 countries as well as new longitudinal studies of policy impact, bolstered by case studies that show how change can occur. The lesson from around the world is that solutions exist from every political perspective.

“The way you get to 187 countries providing paid maternity leave, the way you get to every other major economy providing paid sick leave except for the United States, is that there are conservative solutions, there are progressive solutions, there are middle-of-the-road solutions,” Heymann said.

There’s little disagreement among the general public about the need for paid family leave. The Family Medical Leave Act, a 1993 law that guarantees unpaid, job-protected leave for specified family and medical reasons only for some employees, has proven to be inadequate. Heymann said polls have shown that across party lines and across states, paid family leave is popular.

“People want parents to be able to take time to care for a newborn child. They want adults to be able to take time to care for a dying parent,” Heymann said. “And they don’t want American parents to drop into poverty because of it.”

So, is it possible to achieve gender equality in our lifetimes?

“It is completely within our reach,” Heymann said. “There are solutions that can be achieved in real time, that are feasible.”

Sprague’s answer is similar. “I think we know how to get there. One thing that this book illustrates is how feasible it is and how much of a difference a few key policy changes can make.”

Moreover, Heymann emphasized, the standard arguments against some of those key policies in the U.S. overlook critical evidence about their potential for impact. “Too often, policymakers highlight the costs of paid leave without acknowledging its overwhelming payoffs,” she said. “The evidence is clear that when women in particular have access to paid leave for family caregiving needs, they are far more likely to stay in the workforce — and even slightly narrowing the gender gap in labor force participation would boost our GDP by hundreds of billions. It’s a powerful investment.”

Heymann pointed to studies from McKinsey, the World Bank, and others demonstrating how advancing gender equality pays huge dividends.

“At core, gender equality is a basic human right,” she continued. “But it also yields tremendous economic value—and the U.S.’s continued inaction comes at a high cost to us all.”

To conduct the studies referenced in this book, a multilingual, multidisciplinary research team systematically analyzed the laws and policies of all 193 U.N. member states. They also rigorously analyzed the impacts of legal changes around the world. The book is being distributed through UC Press, and downloadable resources are being made available on the website of the UCLA WORLD Policy Analysis Center.

The WORLD Policy Analysis Center (WORLD) at UCLA is the largest independent global policy data center, capturing over 2,500 social, economic, health, and environmental quantitative legal indicators for all 193 U.N. countries. With an international, multilingual, and multidisciplinary team, WORLD collects and analyzes information on every country’s rights, laws, and policies in areas including education, health, adult labor and working conditions, child labor, poverty, constitutional rights, discrimination, childhood, gender, marriage, families, aging, and disability. Heymann, the center’s founding director, is a distinguished professor of public policy, medicine, and health policy and management at UCLA with appointments in the Fielding School of Public Health, Luskin School of Public Affairs and David Geffen School of Medicine. She is also dean emeritus of the Fielding School.