By Les Dunseith

The newest research center at UCLA Luskin aims to bring together scholars and policymakers to share information so that political leaders can make informed decisions on issues of interest to Latinos, and its Dec. 6, 2017, kickoff event exemplified that goal.

Students, faculty and administrative leaders from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and throughout UCLA were among a crowd of about 175 people that also included elected officials, community activists, business leaders and other stakeholders who gathered in downtown Los Angeles to celebrate the launch of the Latino Policy and Politics Initiative (LPPI).

Attendees had an opportunity to hear keynote speaker Kevin de León, current president pro tem of the California Senate and a candidate for the U.S. Senate, talk about recent legislation on issues related to such diverse topics as labor, good government, the environment and education. He was then joined by a panel of experts in a spirited discussion of the current national political climate and major issues that directly impact Californians, particularly Latinos and other communities of color.

“In the great state of California, we celebrate our diversity,” de León told the crowd. “We don’t ban it, we don’t wall it off, and we sure as hell don’t deport it.”

In his speech, de León talked about the state’s efforts to deal with climate change, to improve education and to provide a safe haven for all residents. For example, Senate Bill 54, the California Values Act, which de León championed, creates a safe zone at “our schools, our hospitals, our churches, courthouses and other sensitive locations so our undocumented immigrant communities can live their lives and conduct their businesses without fear.”

De León declared, “If this president wants to wage a campaign of fear against innocent families, he can count us out. Because the state of California won’t lift a single finger or spend a single dime to become a cog in the Trump deportation machine.”

One of the goals of LPPI, which received its startup funding from UCLA Luskin and the Division of Social Sciences, is to provide better access to information — real data, not alternative truths — to help leaders nationwide resist attacks on immigrants and also help them to craft new policies on other issues vital to Latinos.

“It is impossible to understand America today without understanding the Latino community and the power that it wields. And this institute is going to do that,” Scott Waugh, UCLA executive vice chancellor and provost, told the crowd.

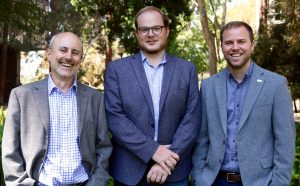

“It’s going to harness all of the intellectual capacity that UCLA has — it’s going to be truly interdisciplinary,” Waugh explained. The co-founders of LPPI — Professor of Political Science and Chicana/o Studies Matt Barreto, UCLA Luskin Dean Gary Segura and LPPI Director Sonja Diaz MPP ’10 — “have a vision that reaches not just inside the School of Public Affairs but reaches out across the campus in areas like health, education, science, the arts — wherever Latinos have made a difference and continue to affect change in a profound way.”

Darnell Hunt, dean of the Division of Social Sciences at UCLA, noted in his remarks that the founding of LPPI comes at a particularly opportune time in American politics. “It goes without saying that we live in challenging times — challenging political times — and the Latino Policy and Politics Initiative will help us make sense of this contemporary setting with an eye toward transformative solutions.”

Barreto, who served as master of ceremonies for the night, spoke about the scope of LPPI’s vision. “We’re not only going to work on immigration reform — we know that immigration reform affects our community and we will work on that — but we are dedicated to work on every policy issue.”

He added, “Whether it has to do with climate change or clean energy, transportation, housing, homelessness, criminal justice or education, we are going to work on that. And we have experts at UCLA who will join us.”

Many of the 20 scholars from across the UCLA campus who are part of LPPI’s faculty advisory council attended the launch event, which began with a networking reception at La Plaza de Cultura Y Artes near Olvera Street, the founding site of Los Angeles itself. As musicians from La Chamba Cumbia Chicha performed, attendees had an opportunity to meet and exchange ideas with the featured speakers and various former and current elected officials in attendance, such as Gil Cedillo, the former state senator and current Los Angeles city councilman. Also in attendance were former California assemblyman and senator Richard Polanco and Amanda Rentería, the former national political director for Hillary Clinton’s campaign and now a staff member in the executive office of California Attorney General Xavier Becerra.

The event wrapped up with a panel discussion and Q&A moderated by Lucy Flores, a former assemblywoman in Nevada who now serves as vice president for public affairs for mitú, a multimedia enterprise that targets young Latinos. Panelists said that bolstering the number of Latino elected officials has been a vital step in bringing about positive change.

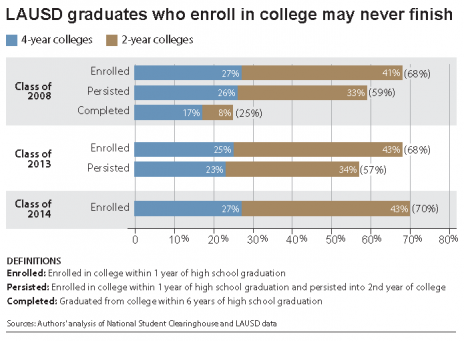

“In the end, votes are what count,” Segura said, noting that Latino’s political influence has not kept up with its rapid population growth. “In order for governments to enact policies that benefit Latinos, it is going to be required that Latinos be a significant share of elected officials.”

Panelist Laura E. Gómez, professor of law at UCLA and former interim dean of the Division of Social Sciences, expanded on that idea in light of a recent wave of disclosures related to sexual misconduct by men in positions of power.

“I think it’s really important … for us to realize that Latinos are a diverse community. We are not just men; we are also women. We are not just straight people; we are also gay and transgender people. And those are important numbers going forward,” she said.

Flores summed it up, “Demographics is not destiny.”

The fact that California often seems to be an outlier in the current national political climate was a recurring topic of the night, with several speakers praising Californians’ resistance to the policies of the current U.S. president. Can the state also serve as a model of progress?

“Despite all of the discord and disunity, California is standing tall for our values,” de León said during his speech. “From education to the environment, from high wages to health care, to human rights, to civil rights, to women’s rights, to immigrant rights, California is proof positive that progressive values put into action in fact improve the human condition regardless of who you are or where you come from.”

De León said California is a leader in innovation — “home to Hollywood and Silicon Valley and the best public university system in the world, the University of California. And we are on the cusp of surpassing the United Kingdom for the fifth largest economy on planet Earth.”

The state is thriving, he said, by doing exactly the opposite of what Donald J. Trump says. “We succeed because we are dreamers, not dividers. We succeed because we double down on lifting people up, not putting them down. We are not going to allow one election to erase generations of progress.”

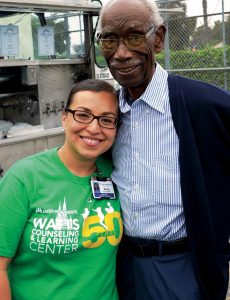

Photo by Les Dunseith

“I want to ask for your partnership, because this is what we need to do — we need to train a new leadership pipeline that is diverse but also represents us substantively,” LPPI Founding Director Sonja Diaz told the audience.

Saying that UCLA is “arguably the finest public institution in the nation, if not the entire world,” De León spoke enthusiastically of the promise that LPPI represents for elected officials such as himself. “We need the empirical evidence, and it’s about time we have this institution established at UCLA.”

Later, when speaking about climate change during the panel discussion, he expanded on the idea that knowledge equals power.

“California has the ability — if we have access to this type of information, this data — to export our policies to other states, even to red states that may not believe in climate change per se,” de León said. “We are showing that, whether you believe in climate change or not, you can actually grow an economy by delinking and decoupling carbon from GDP.”

Access to data is important, but it takes real leadership to turn information into action. “You can have all the academics in the world, all the data, but it doesn’t make a difference if it just sits in a book on a shelf,” de León said. “You have to take that data and move it with political power to actually implement it, execute it, to improve the human condition.”

Segura said it is his goal — and the mission of LPPI — to unite scholars and policymakers for mutual benefit, helping academics turn research into actionable policy.

“Facts do matter. Facts may not be a good way to sell people who don’t want to hear them, but lots of well-meaning elected officials want information,” Segura said. “One of the jobs of the institute is going to be to take the data out of those dusty books and put them in the hands of policymakers in a useful time frame so that policymakers can respond.”

The Latino Policy & Politics Initiative is a comprehensive think tank around political, social and economic issues faced by California’s plurality population of Latinos and other people of color. Anyone interested in providing financial support may do so through the UCLA giving page for LPPI.

Additional photos from the event may be viewed in an album on the UCLA Luskin feed on Flickr. Watch the video of our speakers and panelists.