By Les Dunseith

Today, Los Angeles is celebrated as an inclusive city known for tolerance, diversity and a welcoming attitude to immigrants from around the globe. Just 25 years ago, however, it was a city seemingly afire with racial distrust, anger and violence.

Things have changed so much for the better since the L.A. riots. Haven’t they?

That question was the focus of a weekend filled with reflection, debate, education and artistic interpretation as the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs joined with several partners to sponsor a series of special events marking the April 29, 1992, anniversary of the start of civil unrest that followed the acquittal of four white LAPD officers in the videotaped beating of a black man, Rodney King. On that day and for five days to follow, looting, arson and violence led to dozens of deaths and $1 billion in damage in and around South Los Angeles.

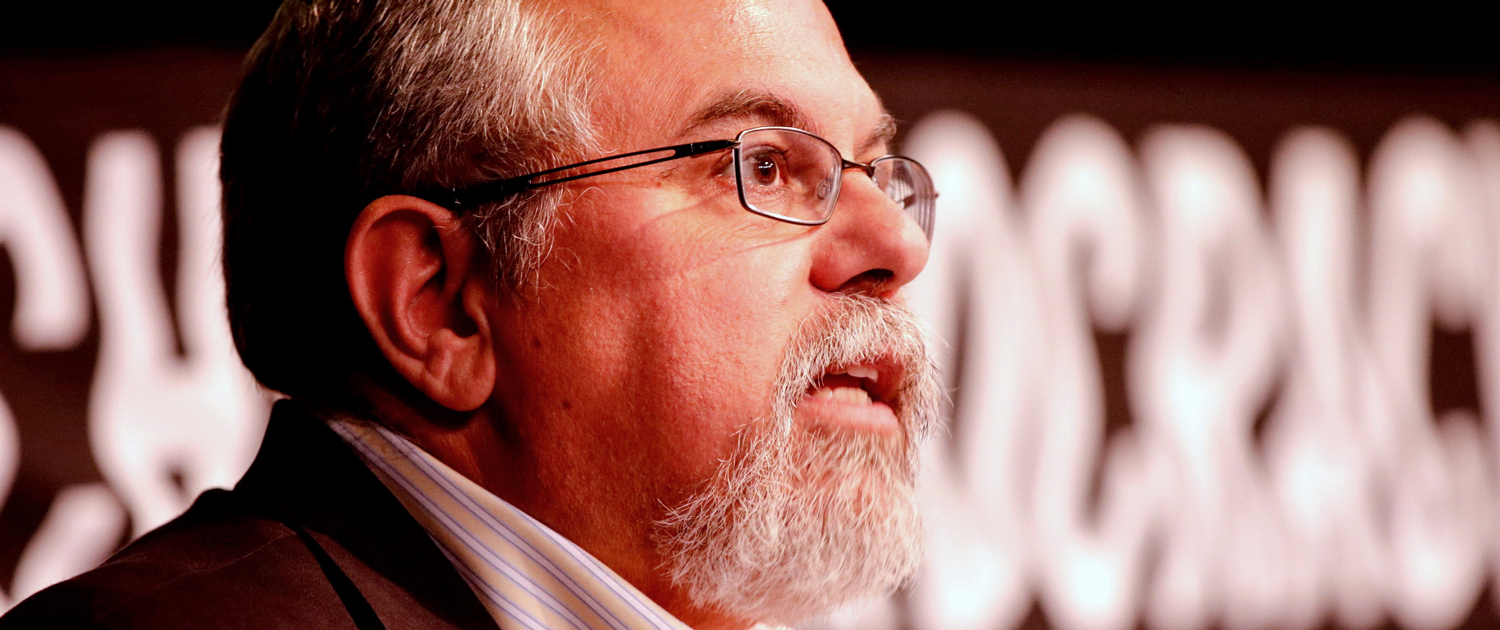

The memories of those days vary starkly depending on an individual’s perspective and background, a fact that was highlighted by Dean Gary Segura during his opening remarks at one of the panel discussions co-sponsored by UCLA Luskin as part of Flash Point 2017, which was held on the UCLA campus and in Little Tokyo on April 28-30.

“L.A. uprisings. L.A. civil unrest. L.A. riots. L.A. rebellion. Indeed our very language captures the idea that the perspective that different communities have on the event, and what they understood about its causes and consequences, really depended on where you sat at the moment at which it occurred,” Segura said.

One of those unique perspectives is that of the Asian community, particularly people of Korean descent. Korean immigrants and Korean Americans who could only afford to set up shop in the poorest neighborhoods of Los Angeles owned many businesses in low-income areas that were predominantly black at the time.

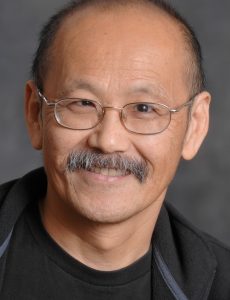

“When you look at one specific story out of 1992, the story of Korean Americans is that they are a dynamic community that was undergoing really dramatic demographic and political transformation,” said Taeku Lee, professor of law and political science at UC Berkeley. He was keynote speaker for a session that took place at the UCLA Luskin Conference Center on the opening day of the anniversary series, which was coordinated by the UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion.

In 1992, cultural and language barriers, plus racial mistrust in some cases, had led to simmering resentment among some African Americans toward Koreans. In the riots, resentment turned to rage, and looters and arsonists disproportionately targeted Korean businesses. Today, Lee pointed out, the Korean words for April 29, Sa-I-Gu, hold great cultural and historical significance to all people of Korean descent.

The Korean perspective of the 1992 unrest was also important to Saturday’s events, held in conjunction with the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival at the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo.

Segura noted that the enterprise represented an expansion of an ongoing speaker program known as the Meyer and Renee Luskin Lecture series to also include other types of programming on topics of historical and political significance. In this case, the weekend included speeches, panel discussions, art and multimedia exhibits, and the screening of two different films related to the 25th anniversary of the riots.

“The three-day Flash Point program is exactly what I had in mind when I asked to expand the Luskin Lecture Series into a series of public forums, and we at the Luskin School are proud to be a sponsor of this thought-provoking examination of the 1992 Los Angeles uprising,” said Segura during his introduction of filmmaker Dai Sil Kim-Gibson.

Her documentary film, “Wet Sand: Voices from L.A.,” offers a look back at the causes of the riots from the perspectives of various ethnic groups. It also speculates about whether some of those causes linger just below the surface today.

“Things have changed since the 1992 L.A. riot, and the aftermath; I think it stimulated people to think. So racism, overtly, went away a little bit. But the danger was that racism went inside of the people,” Kim-Gibson said during the panel discussion that followed the film. “Overt racism is sometimes easier to deal with than the racism that is inside. So we have to really follow up and talk about what really happened after the L.A. riot and what we still have to do.”

UCLA Luskin’s Abel Valenzuela, professor of urban planning and Chicano studies and director of UCLA’s Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, moderated the panel discussion.

“From destruction, from ashes, we can see rebirth and growth,” Valenzuela said of the progress that has been made since 1992. “There’s lots to be proud of, though we still have lots of work still to do.”

Only through greater understanding can progress result, said panelist Funmilola Fagbamila, the winter 2017 activist-in-residence at UCLA Luskin. She noted that distrust between blacks and Koreans at the time was often rooted in similar struggles just to survive, to provide for their families.

“We need to talk about unity that addresses the difficulty of power relations among different communities of color,” said Fagbamila, an original member of Black Lives Matter.

“It means looking at the role of anti-blackness in the way in which Korean Americans and Korean immigrants were in conversation with each other during this time. We have to be critical in how we are engaging each other,” she said. “But also loving. Our attitudes need to change in order to change the issues.”

Another panel on Saturday focused on the evolution of communication since 1992 to today’s world in which people with a story to tell can go directly to their audience via YouTube or social media rather than relying on mainstream news outlets.

Panelist Ananya Roy, professor of urban planning, social welfare and geography and director of the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin, said the media narrative quickly became about interracial and interethnic conflict during the 1992 unrest. The same might not hold true today.

“We are at a slightly different moment. This is perhaps the success of Black Lives Matter,” she speculated, “that it has drawn attention to the ways in which we cannot see these moments of violence as those of individual participants, but we’ve got to see them as structural violence. We’ve got to see this as our liberation being bound up with the liberation of others.”

Today, she said, “even mainstream media has to pay much more careful attention to state violence, in particular police violence, in a way that I do not recall in the 1992 coverage.”

UCLA Luskin also served as sponsor of a screening of the feature film “Gook” on Saturday, during which a packed auditorium of attendees witnessed a fictionalized story of two Korean American brothers, owners of a struggling shoe store who have an unlikely friendship with a streetwise 11-year-old African American girl. Then the Rodney King verdict is read and riots break out.

Filmmaker and lead actor Justin Chon was on hand to introduce his film and answer questions about it. He was joined on stage by cast members and others who participated in the film’s production.

On Sunday, an artist talk in Little Tokyo featured works by Grace Lee, Grace Misoe Lee and Patrick Martinez. Among the works was “Ktown92,” an interactive documentary in process that disrupts and explores the 1992 Los Angeles riots through stories from the greater Koreatown community.

Flash Point 2017 and the weekend’s other events were produced in partnership with the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin, Ralph Bunche Center for African American Studies at UCLA, UCLA Asian American Studies Center, UCLA Center for EthnoCommunications, UCLA César E. Chávez Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies, UCLA Department of History, UCLA Institute of American Cultures, UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, and Visual Communications.

“This report is a sobering snapshot of the inequalities that have persisted in South Los Angeles 50 years since the 1968 report,” said

“This report is a sobering snapshot of the inequalities that have persisted in South Los Angeles 50 years since the 1968 report,” said

Despite recent gains in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights in the United States such as gay marriage and the right to serve openly in the military, the fight against equality for LGBT people appears to be gaining strength, according to

Despite recent gains in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights in the United States such as gay marriage and the right to serve openly in the military, the fight against equality for LGBT people appears to be gaining strength, according to