By George Foulsham and Mary Braswell

A critical shortage of places to live — especially safe, affordable housing — has afflicted neighborhoods across California, the nation and the world. As politicians and civic leaders debate zoning laws and developer incentives, one principle is too often ignored: housing justice.

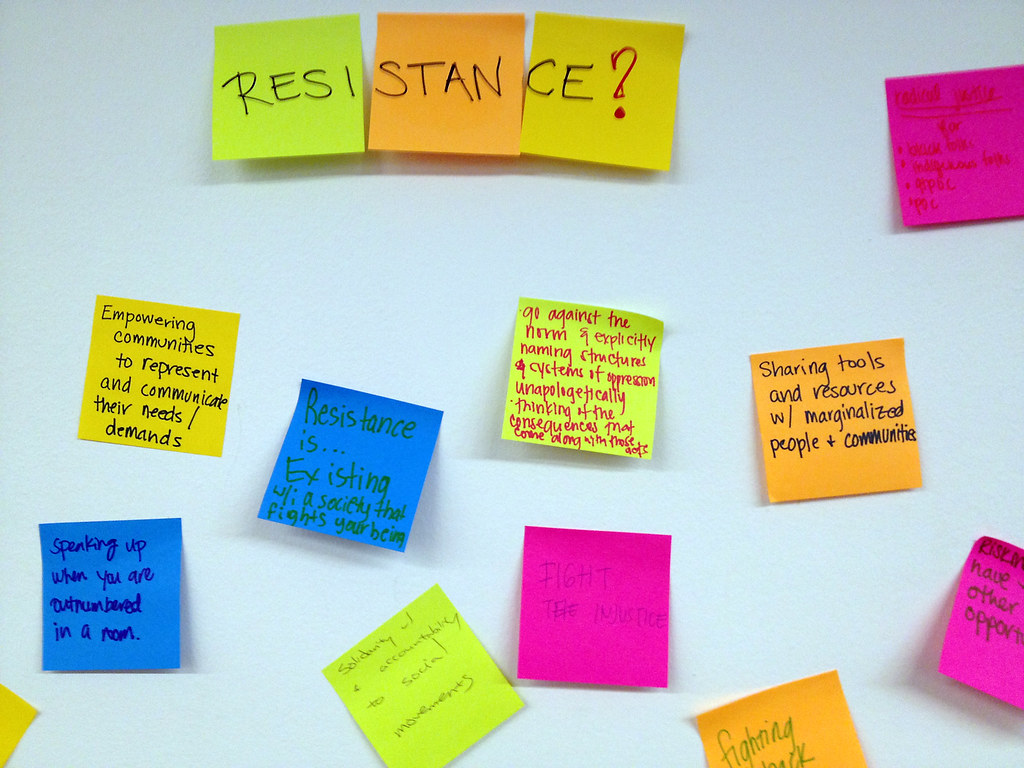

To fill this gap, the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs has entered into a first-time collaboration with the Activist Graduate School (AGS) to offer a new class called “Housing Justice Activism and Protest: Past, Present, and Future,” which weaves together history, theory and strategy in a curriculum designed to forge equitable solutions to the housing crisis.

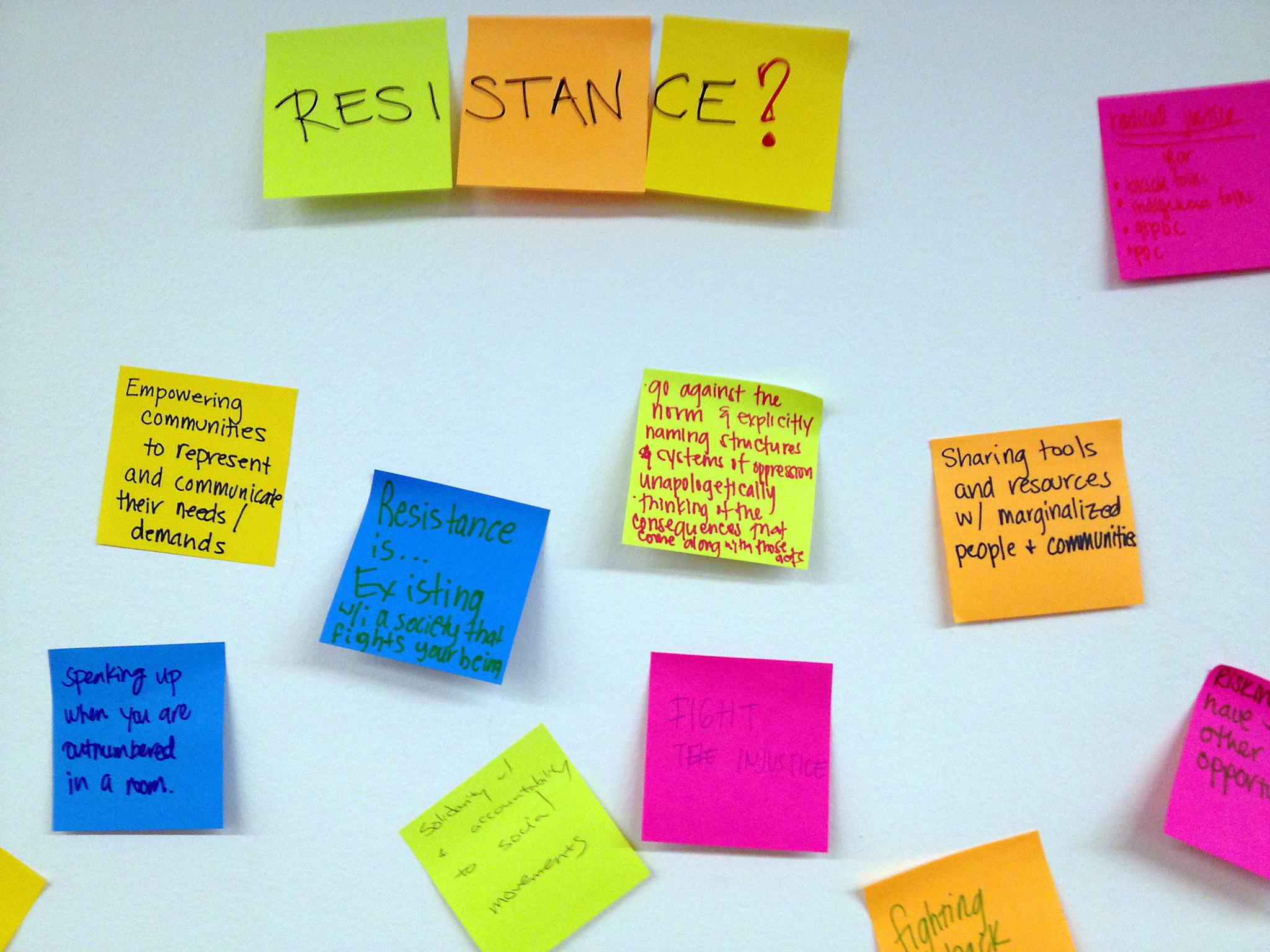

Housing injustice takes many forms, and each week the course will delve into a different facet: Mobilizing renters threatened by unfair evictions. Cracking down on predatory financing. Viewing public housing in a global context. Understanding tensions among tenants, landowners and law enforcement.

Open to all UCLA graduate students, the winter-quarter course quickly filled to capacity. Class sessions are being recorded to eventually be made available for online study worldwide through AGS, a learning community designed to meet the needs of activists.

“Activist Graduate School is part of our ongoing efforts at the Institute on Inequality and Democracy to develop strong alliances between university-based research and movement-based advocacy and activism,” said Ananya Roy, professor of urban planning, social welfare and geography at UCLA and director of the Institute, which is hosting the course.

“We call this ‘teach, organize, resist,’ and the idea is to train graduate students at UCLA to make change in unequal cities as well as to share this training and pedagogy with activists and young professionals nationwide,” said Roy, who is co-teaching the course with Micah White, founder of AGS, co-creator of the Occupy Wall Street movement and one of UCLA’s 2019 Activists-in-Residence.

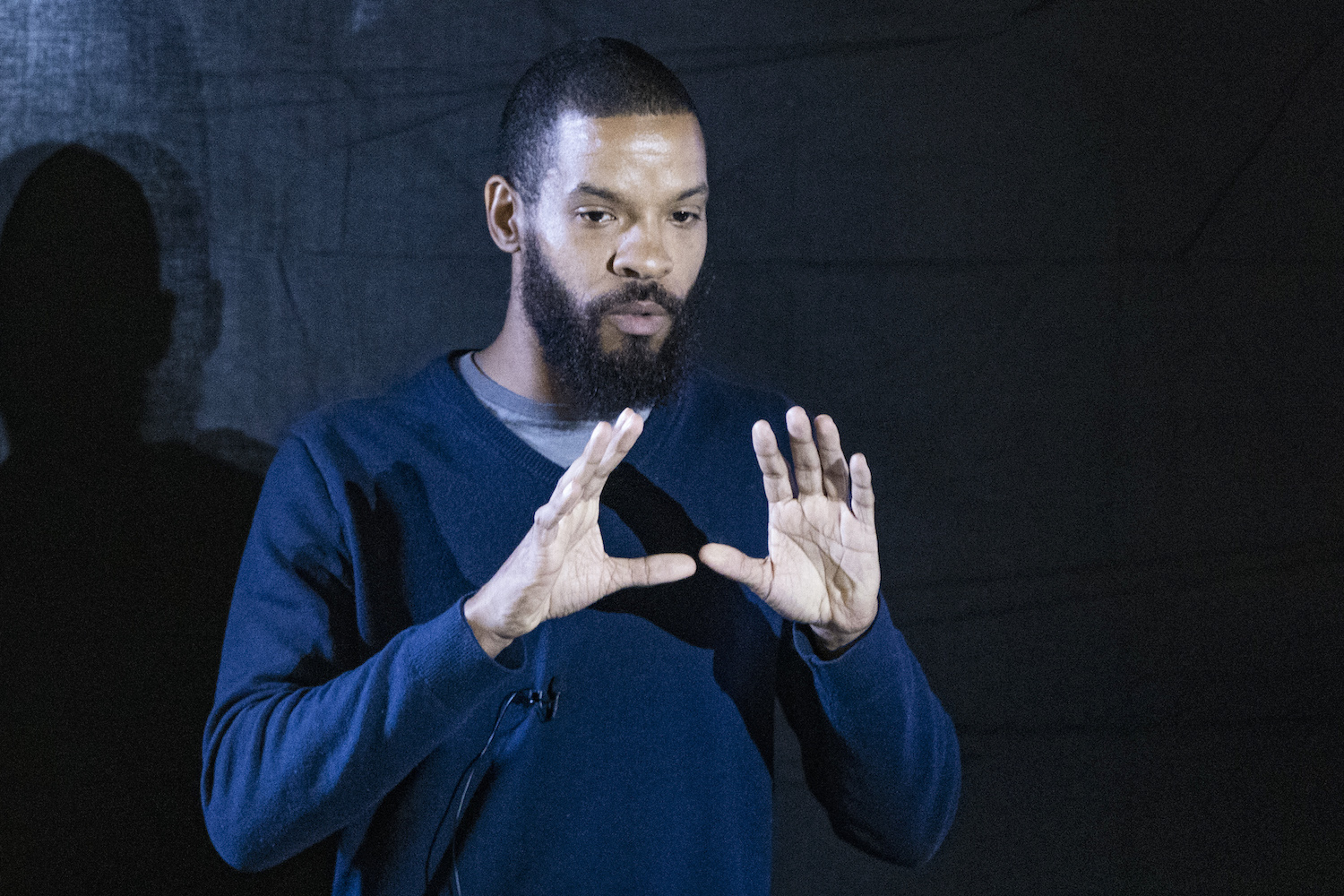

“We try to teach how to think like a critical activist — focusing on theory of change, strategy, history — without presuming to teach what will be effective or what will spark a social movement,” White said.

“One of the pedagogical principles of AGS is that activism cannot be taught in a prescriptive manner,” he added. “This is because any tactic that was useful in the past is likely to be ineffective in the future, and social movements nearly always come as a surprise; therefore, it is nearly impossible to predict which campaigns will take off.”

During the first class of the quarter, grassroots organizing and renter revolts took center stage. René Christian Moya, an activist with the L.A. Tenants Union and other advocacy groups, shared tactics learned in the trenches of the housing justice fight — including rent strikes and the public shaming of landlords, developers and politicians.

“The law is not on the side of tenants,” Moya said. “We have to be very, very clear and honest with tenants when we’re dealing with them that ultimately it is not the law that’s going to save them, and it’s damn well sure not going to be their elected officials. It’s going to be through their own power.”

The roots of housing injustice in the United States run deep, added speaker Marques Vestal, a Ph.D. candidate in UCLA’s History department.

“Think of all the ways that tenants are maligned or completely disregarded in everyday culture,” Vestal said. “One of our most dangerous problems … is that most of society thinks landlordism is a natural hierarchy of land.”

Students in the class represented graduate programs from across campus: Geography, History, Law, Public Health, Chinese Studies and all three Luskin School programs — Urban Planning, Social Welfare and Public Policy. By the end of the course, each student will have developed a campaign tackling some area of housing injustice.

Dian Tri Irawaty, who came to UCLA after spending years as a tenant activist in Jakarta, Indonesia, was immediately drawn to the curriculum.

“I want to empower myself with academic tools while doing activism at the same time,” said Irawaty, a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in urban geography and member of a graduate student working group at the Institute on Inequality and Democracy.

She hopes the course will enrich her research into housing and evictions in the global South and ultimately plans to bring her new skills and scholarship back to Jakarta to foster change.

“History, theory and strategy are really important if we want to win the fight for housing,” Irawaty said.

The course was designed in collaboration with Institute graduate student researchers Terra Graziani and Hilary Malson of UCLA Luskin Urban Planning.

“This continues the tradition of student-organized courses here at UCLA where we come together and create a curriculum that we feel is urgently needed but otherwise missing,” Roy said.

Graziani, who is also co-director of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, Los Angeles, said the course will spur graduate students “to not only think like activists, but to think of ways that their scholarship can take up activists’ mandates for justice-oriented research.”

At the inaugural class, tenant organizer Moya issued a challenge to the gathered students. “You’re not here just to hear me lecture about this. You’re not here to hear any of us just tell you what we already know — that we’re suffering a horrible housing crisis that impacts all of our communities,” he said. “We need every single one of you here to jump into this movement.”

Support for the course is provided by the Institute on Inequality and Democracy, Urban Planning and Social Welfare from the Luskin School. Other UCLA supporters are the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, Institute of American Cultures and the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies.

Cristina Barrera contributed to this report.

Follow the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin on Twitter @challengeineq to learn more about AGS featured speakers and for updates about the UCLA Activist-in-Residence Program.

View more photos from the Housing Justice Activism and Protest course on Flickr.