Repeating History But Innovating: Social Housing and Urban Policy in Latin America Blog post from Professor Paavo Monkkonen via Global Public Affairs @ Luskin

By Paavo Monkkonen, Faculty Cluster Leader of Global Urbanization and Regional Development; Professor of Urban Planning

Although the major urbanization boom in Latin America occurred many decades ago, cities across the continent continue to grow rapidly and problems associated with adequate, affordable, and well-located housing are widespread. Housing policies designed to provide new, subsidized housing to low-income households still dominate (though the state no longer builds housing, providing assistance through the housing finance system instead), in spite of agreement among most experts that they are not the best way to ameliorate urban housing problems.

Unlike the inner-city public housing projects of the United States, public housing projects in Latin America are generally composed of small single-family homes located in far-flung outskirts of cities. They therefore suffer not only from problems associated with concentrated poverty, but more importantly a lack of urban amenities, poor public services, and a large distance from employment opportunities. Brazil’s most infamous peri-urban public housing development Cidade de Deus, portrayed in a film of the same name, was built in 1964 yet the new housing policy Minha Casa, Minha Vida is criticized for many of the same problems. Mexico has the largest finance driven social housing program in Latin America, and as a recent OECD report documents, faces major problems in new housing developments that lack public services, access to jobs, and as a result, among the highest vacancy rates in the world. In fact, scholars are framing the Mexican housing policy as a social interest housing planning disaster. Social housing programs in Chile and in Colombia face surprisingly similar criticism.

The philosopher George Santayana famously stated, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Kurt Vonnegut’s more prescient and useful retort is that “we’re doomed to repeat the past no matter what.” Thus, perhaps the challenge to policymakers (and scholars) is simply to make sure our iterations of past approaches are innovative in some aspects. And there are innovations. Two notable areas are first, the application of inclusionary housing ideas in the design of public housing programs, and second, policies to promote densification of more accessible parts of cities with services.

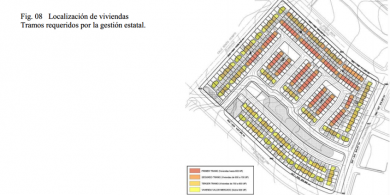

Chile is the farthest along in taking seriously the idea of inclusionary zoning/housing – regulations that promote the integration of market-priced properties and subsidized properties in the same multi-unit buildings or within neighborhoods – in public dialogue and action. A notable example is the Project of La Chimba in the city of Antofagasta in northern Chile built from 2003 to 2005. In spite of shifting to demand-side housing subsidies in the 1990s, low-income homebuyers continued to be pushed into certain types of new housing developments that shared the same problems as those previously built by the public sector, including social segregation. To address this problem, a project was developed in Antofagasta that purposely had a range of housing types in the same neighborhood, including some market rate and some affordable to voucher holders. A case study of this project by Hector Vasquez Gaete will be available shortly from Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

New policies to promote housing construction in central cities are also being implemented in Latin America, with the goal of adding housing where there are already services, amenities, and access to employment. For example, property tax rates on vacant land in Brazil are on average five times higher than on land that has been developed. More aggressively, Bogota (which also has higher tax rates for vacant land) implemented a policy that forces the sale of vacant land that is not developed within two years of being identified. Land is then developed for social housing.

In order to make progress in the design of housing policies so that they do not repeat past mistakes and improve the lives of those living in Latin American cities, comparative research on what works, what does not, and why, is necessary. Fortunately, this type of investigation is ongoing and several notable examples have been recently completed; for example an overview book from the Inter-American Development Bank, a paper by Eduardo Rojas, and an edited volume on the inner-suburban neighborhoods of Latin American cities by Peter Ward, Edith R. Jimenez Huerta, and Mercedes Di Virgilio.

Original post at http://global.luskin.ucla.edu/