By Les Dunseith

Antonia Izuogu, a second-year urban planning student, came to UCLA with an interest in affordable housing, and as a Bohnett Foundation fellow, she has had an opportunity to participate in initiatives relating to homelessness for the Los Angeles mayor’s office.

“I was homeless at one point, actually twice, within my childhood,” Izuogu said.

But when the time came to choose a topic for her required capstone research project, Izuogu chose to pursue an emerging interest in the community development side of urban planning, particularly work cooperatives. She ended up doing a feasibility study for a partner group of the Downtown Crenshaw Rising community organization.

“My capstone and my mayor’s work didn’t really touch each other — they’re just two passions of mine that I was able to work on this past year,” Izuogu said.

Read about Graham Rossmore’s capstone on al fresco dining and its influence on policy in L.A.

Throughout the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, soon-to-graduate students pursue monthslong deep dives into pressing policy issues with social relevance. In the Master of Urban and Regional Planning (MURP) program, the capstone experience may involve individual students like Izuogu working with community groups, government officials or public agencies to investigate real-world policy issues.

Other MURP candidates work in small teams or participate in one of two longstanding group-learning opportunities — the Community Collaborative and the Comprehensive Project classes.

The Community Collaborative is a unique pairing of students with community-based organizations in need of the expertise that academic researchers can provide. In turn, the students benefit from the insights of activists and others with lived experiences, fostering a mutual learning experience.

This year’s Spatial Justice Community Collaborative course was taught by Professor Ananya Roy, and it focused on issues relating to life in homeless encampments. Class participants included individuals who had been among the unhoused populations at encampments forcibly cleared by law enforcement.

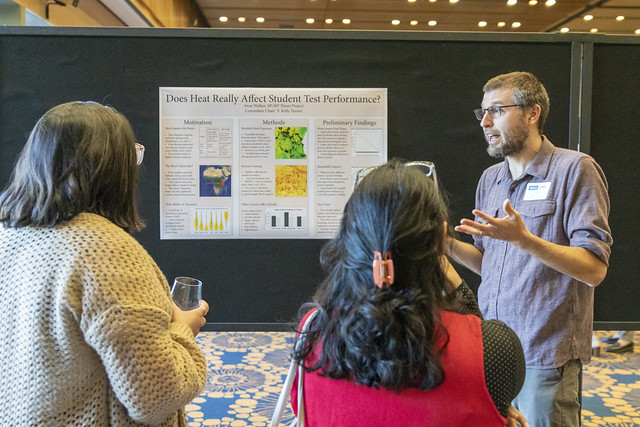

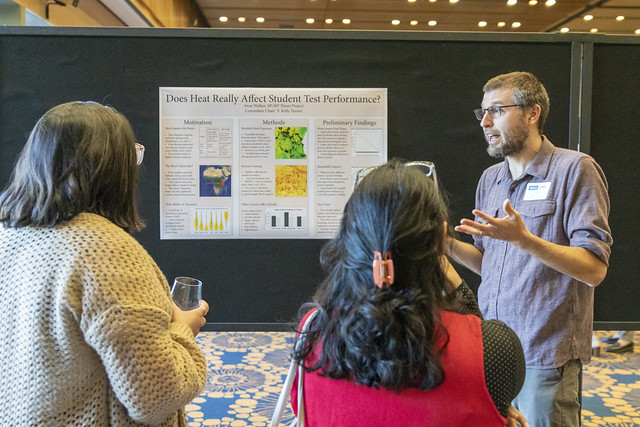

The second group option is the Comprehensive Project class, which is a more traditional group project experience led by a faculty member who directs student researchers through an examination of a complex policy issue. Interested students had to apply nearly a year in advance to be admitted to the class, which this year focused on heat equity under the direction of Gregory Pierce BA ’07, MURP ’11, PhD ’15, an adjunct associate professor of urban planning and co-director at the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

The client for the class of 13 MURP students was Marta Segura, chief heat officer and director of the city of Los Angeles’ Climate Emergency Mobilization Office, which is known informally as CEMO. Segura and her staff are developing strategies for Los Angeles’ efforts to deal with rising heat from climate change in an equitable manner.

“The work that CEMO is doing is really important, and they have a huge mandate, particularly on heat,” Pierce said. “But they have very little actual staff capacity to do a lot of the research they need to do.”

The office’s agenda is driven by nonprofit and community-based organizations, which “aligns with the social justice orientation of the Luskin School, for sure,” Pierce said.

The students, whose research has also been guided by Ruth Engel, project manager for environmental data science at the Luskin Center for Innovation, have divided the task into three subtopics — cooling centers, emergency response and bus shelters. Their final report was due to CEMO on June 9, just one week before UCLA Luskin’s commencement.

Pierce said the report commends Los Angeles for being at the forefront of government efforts on extreme heat, but it notes room for improvement in terms of action and having systems in place to ensure public safety and equitable distribution of resources.

“This is a pretty new space for a lot of cities, so it’s in its early days,” Pierce said of the strategic planning. “But there’s a lot of work to do to really follow through on what needs to be done as it gets hotter all the time.”

Among the students’ recommendations:

- increasing cooling center density in underserved areas of the San Fernando Valley and Harbor Gateway;

- developing heat responses in cooperation with unhoused residents and their advocates to better meet their needs;

- utilizing more expansive definitions of heat emergencies and heat warnings, with lower heat thresholds than existing city policy;

- shifting the priority for bus shelter development — often guided in the past by political considerations or the revenue potential of shelter advertisements — toward geographic equity, thus prioritizing the placement of shelters in hotter neighborhoods with high numbers of bus riders.

Among the bus shelter group was Miguel Miguel, a second-year urban planning student who grew up in an area of the San Fernando Valley that often sees dangerously high temperatures.

“I grew up seeing people suffer from what happens without adequate heat protection. It was really important for me to be involved, and to bring lived experience and emotional compassion into this project,” Miguel said. He said the capstone experience helped position him to play a role in shaping the nature of environmental justice in Los Angeles moving forward.

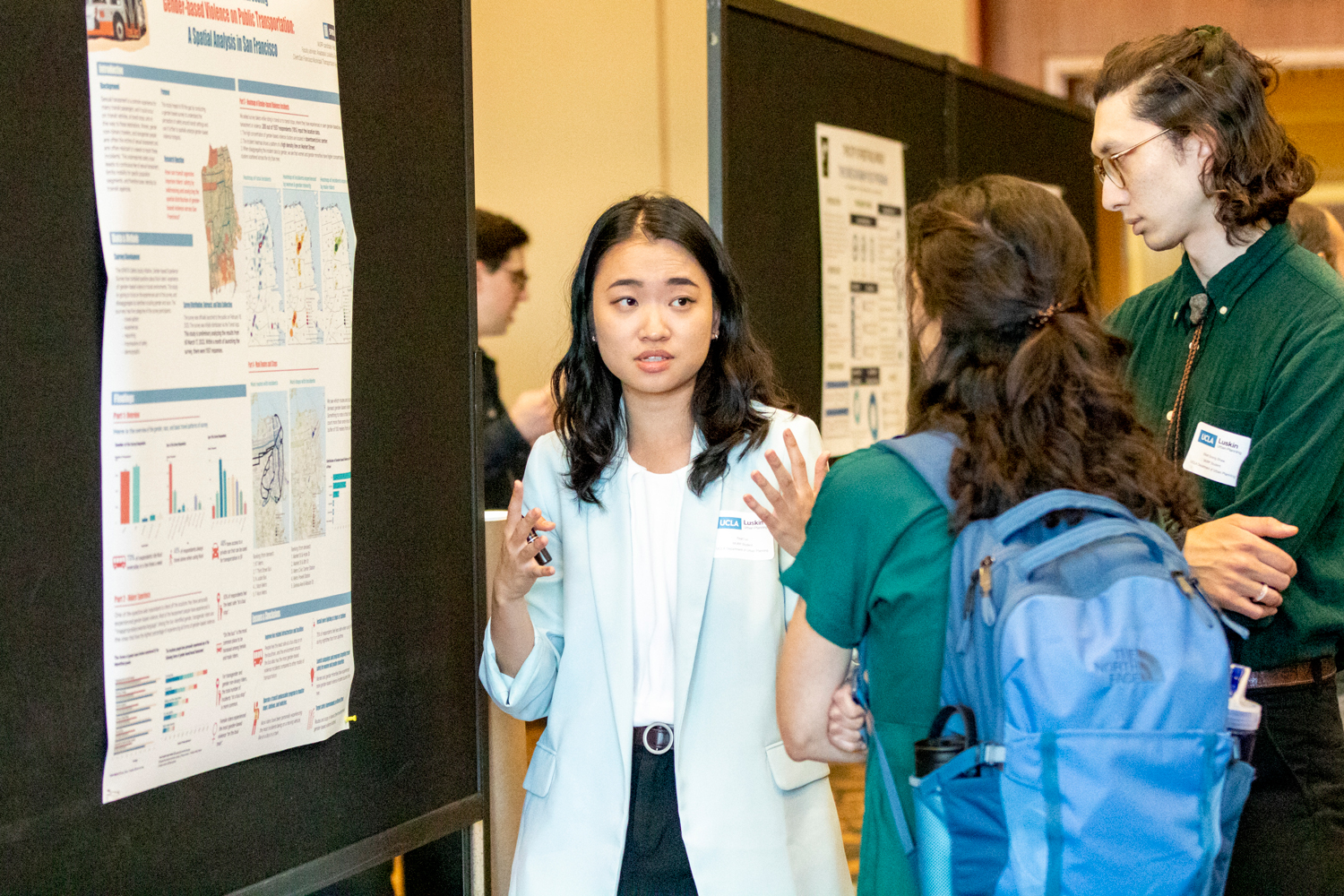

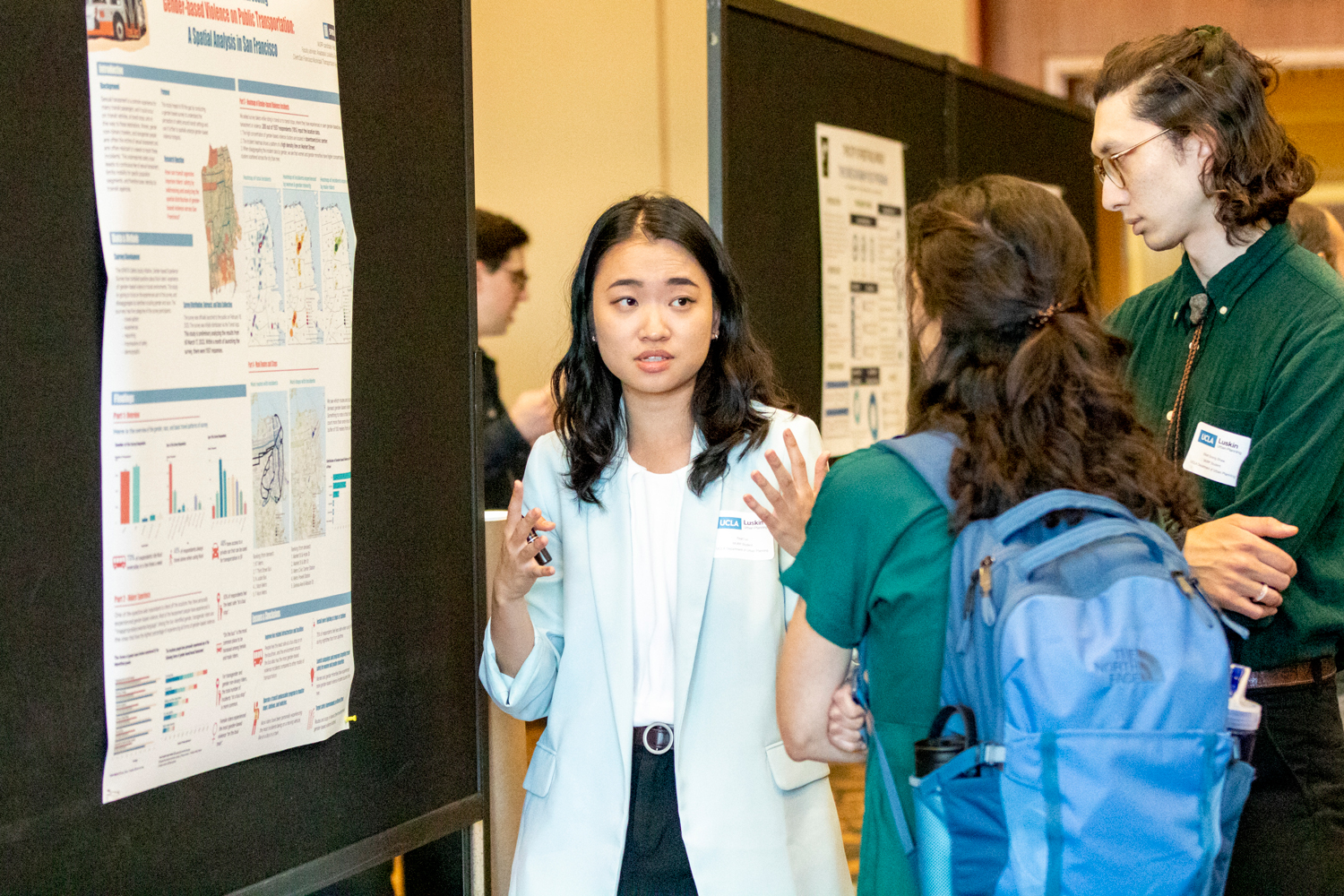

Pearl Liu’s capstone research looked into safety issues on public transit in San Francisco. Photo by Les Dunseith

Equity was a foundational element of many urban planning capstone projects completed this year, including one by Pearl Liu. Her capstone project focused on public transit safety issues among women and gender minorities.

An international student, Liu was accustomed to getting around her home city of Taipai, Taiwan, via ready access to a clean, safe public transit system. She didn’t find the same conditions in Los Angeles or San Francisco, where she did an internship with the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, or SFMTA.

“As a woman, and living without a car at all for two years in L.A. and also in S.F., I totally understand how women feel when they travel,” Liu said. “I have all these struggles. I have all this … built-up anger and complaints. I hope to change all these things as a transportation planner.”

At SFMTA, she had an opportunity to become familiar with a grant-funded gender equity initiative. During the internship, she started building a transit safety survey that eventually led to her capstone project.

The survey was launched through the Transit app for riders of San Francisco’s public transportation system, known as the Muni. Within a month of launching, a total of 1,613 people had filled out the survey.

“Sexual harassment is a very common experience for many transit passengers, but especially to women and gender minorities — transgender people and those with non-binary gender identities,” Liu said.

Another MURP, Greer Cowan, worked with Liu on the survey about Muni usage and travel patterns among women and gender minorities in San Francisco, with special attention paid to riders’ experiences. Gender-based violence can include inappropriate swearing or leering, as well as physical assaults. Were the survey respondents victims? If not, had they witnessed it? If so, where? When? Was it on a train, a streetcar or a bus? While riding or while waiting for a ride? Night or day? And so on.

Cowen focused on the reporting of incidents, noting that many people only tell their friends or family, so authorities have insufficient data to take action. Liu’s capstone focuses more heavily on how respondents feel about their safety, and where incidents occurred.

Among gender minorities, more than half of respondents felt the least safe at a bus stop, for example. But for male and female transit users, harassment and the fear of it happening was more intense during transit rides, particularly on buses.

She did a spatial analysis of the data, overlaying the incident maps with the transit lines and transit stops, and produced a “heat map” to determine places with higher concentrations of incidents of gender-based violence. The bus system showed the most problems.

“It is mostly happening in the downtown area,” she found. “A lot of it was on Market Street,” in the financial core of San Francisco.

Therefore, her capstone recommends that safety and equity initiatives by the SFMTA focus heavily on bus routes near Market Street. She also advocates for a safety toolkit for women and gender minorities. A transit ambassador program to monitor stops, stations and vehicles could focus more attention on buses. And the No. 1 suggestion to benefit women and gender-minority riders? Install more lighting.

“That always — always — is something that we’re pushing for,” Liu said. “Most people … feel at least somewhat safe during the daytime or when a station is well-lit.”

Liu said the capstone project helped refine her career aspiration.

“This project … it really sparked an interest in me in how safety is so important in public transit,” Liu said, “and I feel like that has given me a passion to want to work in this area in the future.”

In some cases, the capstone projects serve as a reality check for the client organizations. Such was the case for Izuogu’s research for Downtown Crenshaw Rising.

Her capstone project focuses on cooperative ownership, or co-ops, as a means to foster economic development in lower-income areas. The project was built on work that had been done by the previous year’s Community Collaborative class — a project that ended up being recognized by the American Planning Association’s Economic Development Division for its Student Project Award.

That project had recommended several possible ways to improve economic conditions in the Crenshaw area of Los Angeles, and her client was interested in the possibility of creating a cooperatively owned manufacturing facility in the area.

Izuogu is a native of North Carolina who had gotten her undergraduate degree at Spelman College, a historically Black college in Atlanta, Georgia. She was excited for an opportunity to familiarize herself with a neighborhood like Crenshaw with a sizable Black population and do work that might benefit its residents.

“I was like, ‘That sounds really interesting, and I want to work with Black communities, too,’” Izuogu remembered thinking.

Antonia Izuogu, right, had an opportunity to discuss her research with Eve Fouché, who represented the project’s client during the poster event at UCLA. Photo by Les Dunseith

Her feasibility study reflects the Crenshaw group’s interest in launching an eco-friendly manufacturing site for electric vehicle charging stations to take advantage of incentives created by the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that President Biden initiated in 2021.

“I didn’t know much about clean energy before coming [to UCLA] or about working with co-ops. At the same time, I’ve been taking economic development classes,” she said, “so everything was … fleshing out well together.”

Once she delved into the data, however, it became apparent to Izuogu that manufacturing electric vehicle charging stations was not the best option for the group. They lacked startup financing. No one in the group had experience building charging stations, nor connections within the industry. That led to the reality check.

“As a consultant, I’m saying that maybe we should take a pause on that,” Izuogu said. Her capstone report suggests that the group instead create a co-op to install such stations and maintain them as part of a long-term strategic plan that would start small — a bakery/restaurant co-op is already in the works — and build over time into a hub for economic activity.

Izuogu said her client expressed gratitude for her insights.

“They like the idea that I didn’t stop and just say, ‘OK, this is not a good idea. Goodbye,’” said Izuogu, who has urged the group to think beyond Year 1. “Let’s go further than that. And they’ve been very appreciative of the information.”

The capstone project also helped inform Izuogu’s future plans. She will be pursuing a law degree, envisioning a career focusing on “solidarity economy lawyering,” helping small businesses and worker co-ops organize, drafting contracts and successfully navigating government regulations.

Izuogu is a big fan of the UCLA capstone requirement.

“I love how they’re community-based, and this is not just a theory, but we’re actually applying what we’re learning in the classroom,” she said. “I love that I had the opportunity — even though I’m not from L.A. — to benefit the residents here. And getting to know their names and, basically, that we’re continuing this connection between academic institutions and the residents around them.”

View photos of other individual capstone projects in Urban Planning in this Flickr album:

Click the links below to view photos from the numerous other capstone project presentations at UCLA Luskin this year:

Comprehensive Project class

Community Collaborative class

Public Policy’s Applied Policy Presentations

Master of Social Welfare capstones

Undergraduate Public Affairs capstones

Click here and enter “capstone projects” to find stories from previous years and other information about student research at UCLA Luskin.