Lending a Helping Hand Panel discussion at UCLA Luskin highlights what is and isn’t being done to serve the burgeoning homeless population in L.A. County

By Zev Hurwitz

With nearly 60,000 Angelenos struggling with homelessness, local change agents have taken on the task of developing policies and services to address the crisis.

At a Nov. 15, 2017, panel discussion at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, four leaders in the field discussed the challenges and opportunities in finding solutions for the plethora of Los Angeles residents who do not have access to permanent housing.

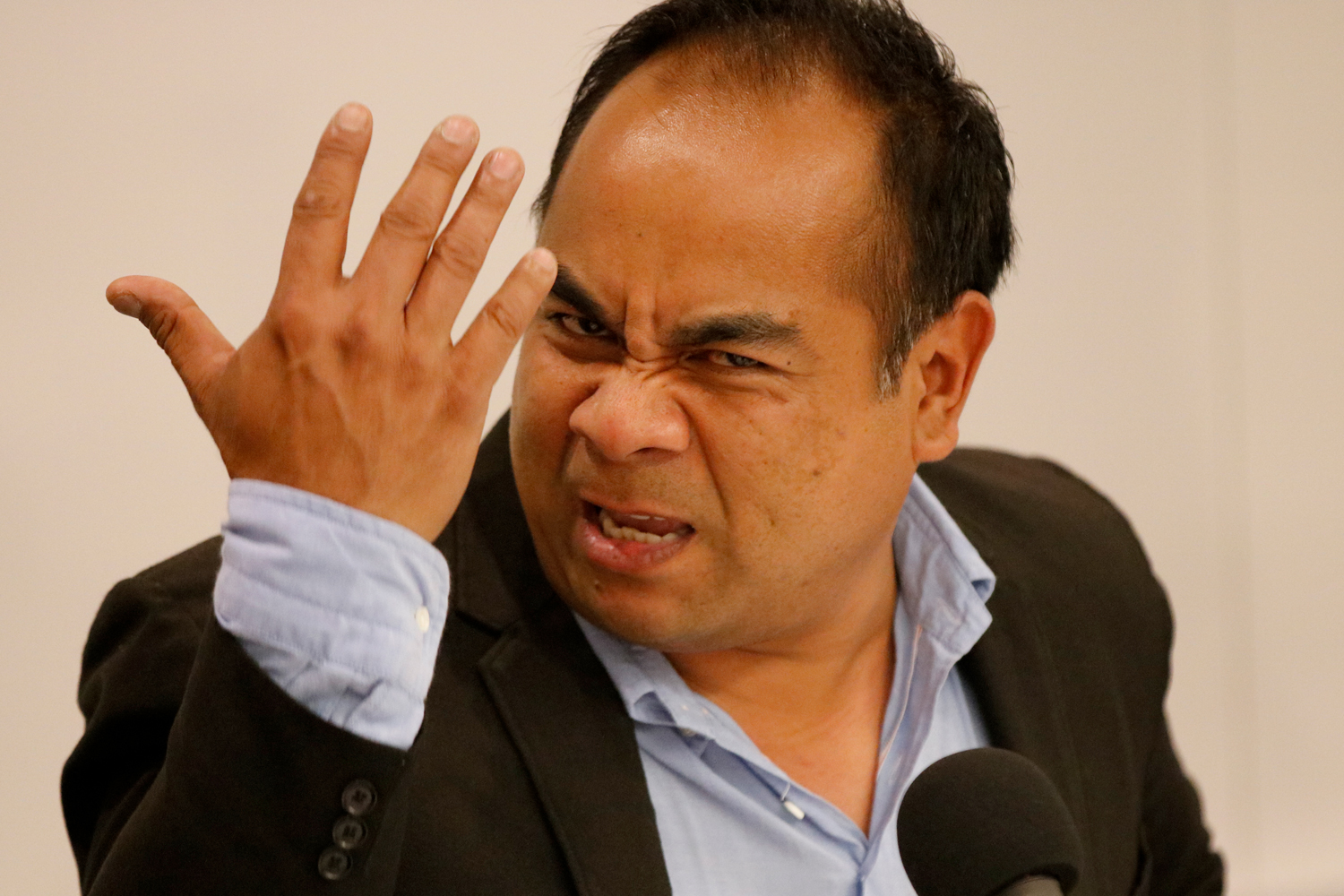

Michael Lens, associate professor of urban planning at the Luskin School, moderated the “Homelessness in Los Angeles” event. Other participants were Jerry Ramirez, manager of Los Angeles County’s homeless initiative; Dora Leon Gallo, CEO of A Community of Friends; Jordan Vega, a current UCLA student and a director of Bruin Shelter, a registered student organization; and Skid Row resident Suzette Shaw.

Lens began the lunch program by noting some alarming homelessness statistics and emphasizing the importance of having the conversation.

“Many of us are familiar with the fact that homelessness is very much on the rise in Los Angeles County,” he said. “In January of 2017, volunteers counted over 58,000 people experiencing homelessness across L.A. County, which is a 23 percent rise over the previous year.”

Lens pointed out that 34,000 of those people are in the City of Los Angeles. Within the city, 25,000 homeless are living “unsheltered” and 11,000 fell into the category of “chronically homeless.

“These are large numbers historically, and they’re large numbers for any city,” he said.

Gallo’s organization, A Community of Friends, works with the local government and other non-profits to provide permanent supportive housing for the homeless. The group, which launched nearly 30 years ago with a grant from the county’s Department of Mental Health, manages 47 buildings and provides in-house services in 18 of those buildings.

Gallo said that her group believes in a “housing first” approach to homelessness and that the model for permanent housing relies on subsidies that enable tenants to pay a fraction of their income in rent, no matter how small that income, without sacrificing the community aspect of living in Los Angeles.

“There really was no housing provider out there that was providing housing that is affordable,” she said. “Our initial founders wanted to create a community where people would have friends.

Earlier this year, L.A. County voters approved Measure H — a tax expected to raise $355 million for homeless services over the next 10 years. The county has developed 21 strategies for addressing homelessness and plans to use Measure H funding to increase housing and services for the county’s homeless. Separately, city voters in 2016 passed Proposition HHH — a bond measure that will directly fund new housing units for low-income and housing insecure Angelenos.

“The 1.2 billion (dollars) from Proposition HHH is for the construction of permanent supportive housing,” Ramirez said. “Where Measure H comes in, it really complements supportive housing because it’s millions of dollars to provide the services. Half the challenge is getting a home for a homeless person — then the hard work begins in keeping them there.”

Ramirez said that the county is hoping to bring in more partners like A Community of Friends to help map out the landscape for new programs and housing units to be funded under Measure H.

“We’re trying to be very inclusive in this process because the county can’t do it alone,” he said. “We’re trying to be inclusive, collaborative and transparent.”

Not all services are being provided at the regional level. Vega helps run Bruin Shelter, which launched last year and currently provides beds for six housing insecure UCLA students. It is the first student-run shelter for peers in the country.

Vega’s personal experience with friends who struggled with homelessness inspired him to take on the role at Bruin Shelter, which helps operate the shelter of Students4Students. Students have access to UCLA medical and social welfare students who provide case management services.

“Our space is kind of small — we’re next to a church,” he said. “We’re currently under construction, hoping to expand, so that we can accommodate more students.”

Suzette Shaw is a resident of Skid Row and knows firsthand the struggles that homeless people can face living on the streets.

“We need to make sure that now that we have the dollars, we are intentionally allocating them and very proactive in allocating those funds to organizations and individuals who make sure that the dollars are addressing the needs of the people,” she said.

Shaw used to run a business and commuted long distances to work to try to make ends meet before moving to Skid Row. She’s now living in a housing unit under her Section Eight voucher, which she had for nine months before receiving a unit. Shaw is very open about her story because people need to have more exposure to homeless in order to address the crisis.

“People tend to stereotype and sensationalize what poverty looks like,” Shaw said. “We have to get real about who we are. We talk about NIMBY-ism, ‘not-in-my-backyard.’ People are either going to live on the sidewalk next to you or else you’re going to make a space for them in the building next to you.”

The issue is one of basic human rights for Shaw.

“I may be poor and I may live on the brink, but I do deserve housing and housing should be a human right,” she said.

The talk was part of an ongoing Housing, Equity and Community series put on by the UCLA Lewis Center, which co-sponsored the event with the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin and the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate. The Lewis Center plans to hold more events in the winter and spring quarters on housing issues.