By Lauren Hiller

During a gathering March 5 at its first home on the UCLA campus, the Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies commemorated 30 years of scholarship, public advocacy and leadership on campus and in the community.

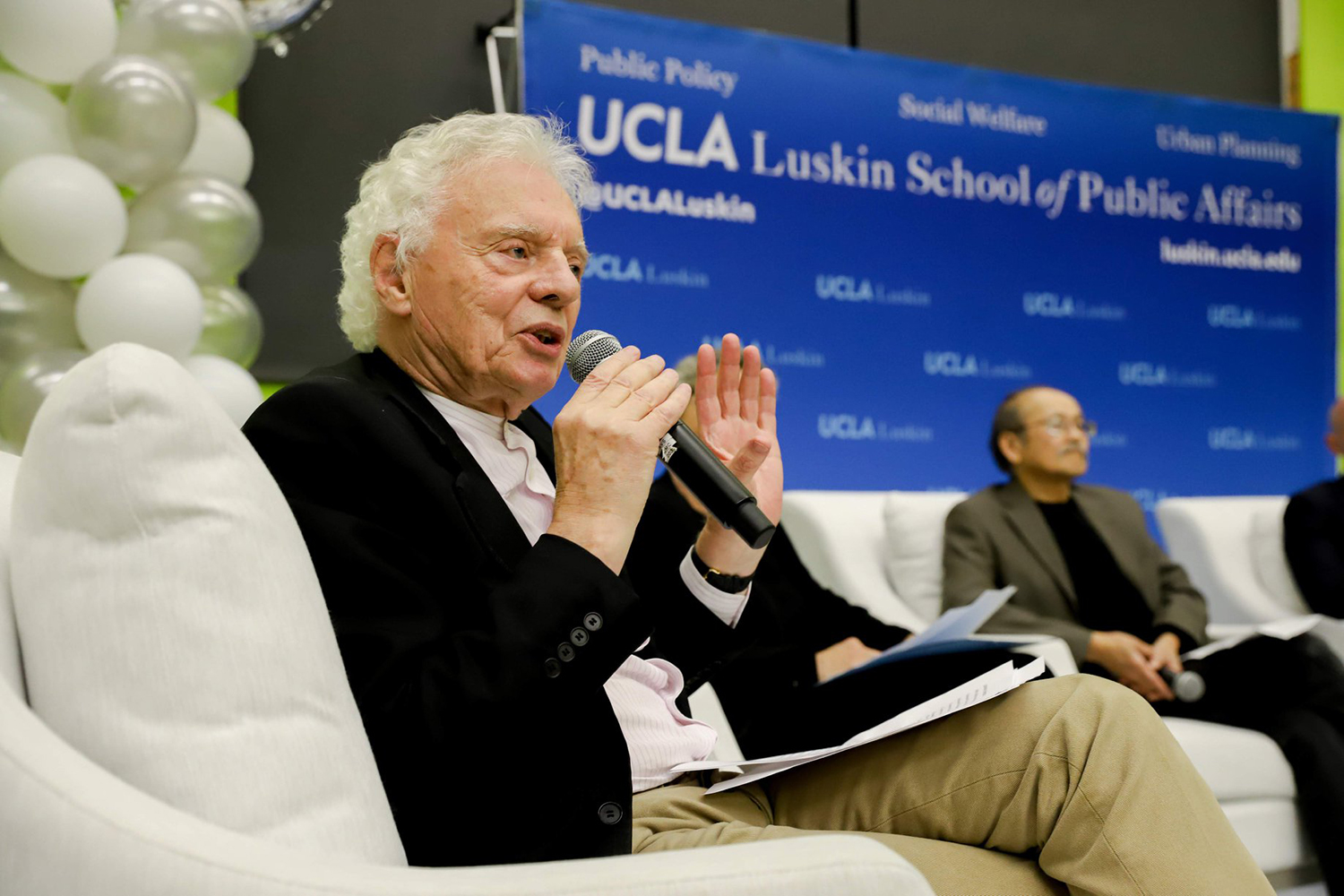

All five former Lewis Center directors — a who’s who of distinguished scholars — joined the current director, Urban Planning Professor Evelyn Blumenberg, at DeCafe Perloff Hall to discuss the milestones and issues facing the region during each person’s tenure. As each director spoke, it was evident that the center’s longevity is rooted in interdisciplinary scholarship and fostering the next generation of scholars.

In 1989, Ralph and Goldy Lewis donated $5 million to endow a research program at UCLA that studied regional policy issues. The following year, the Lewis Center opened its doors in Perloff Hall, the location of what was then known as the School of Architecture and Urban Planning, with founding director Allen J. Scott, distinguished research professor of geography and public policy. Scott was succeeded by Roger Waldinger, distinguished professor of sociology; followed in chronological order by Paul Ong, research professor at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs; J.R. DeShazo, professor of public policy, urban planning and civil and environmental engineering; and Brian D. Taylor, professor of urban planning and public policy.

“My parents both went to UCLA and they believed in the power of public education and need to support the public system,” said Randall Lewis, whose parents were homebuilders and interested in issues of growth, transportation, housing and air quality. “They felt as they were building houses, building communities, that they didn’t want to create problems. They wanted to find solutions.”

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, who joined the UCLA community the same year that Lewis Center was established and received one of its first grants, kicked off the event.

“The Lewis Center best exemplifies the role that we’re asking our research centers to play: push research forward, support the educational mission of the school and its students, and serve as a public forum that disseminates important research-based information and data to a larger public,” said Loukaitou-Sideris, professor of urban planning and associate provost for academic planning.

Launched Amid Regional Turmoil

The early 1990s were a tumultuous time in Los Angeles. The aerospace industry, which was a backbone of the region’s economy, was collapsing. The 1994 Northridge earthquake killed 61 people and caused $6.7 million in damage, crippling major infrastructure like freeways. And civil disturbances fueled by racial injustices, police brutality, and poverty and social marginalization rocked the city.

“Los Angeles looked like, from some points of view, a basket case and getting worse,” Scott recalled. “And so we were, at a very early stage, involved in attempting to build responses to these problems and others.”

Scott and the Lewis Center published a series of working papers focusing on new industry (such as electric vehicles) to replace aerospace and an examination of the nature and causes of the crises in South Los Angeles.

By the time Waldinger took over in 1996, the immigrant population in the Los Angeles region had quadrupled within two decades. Yet, research on the impact of immigration on the Los Angeles region lagged behind frequently studied cities like Chicago and New York. The Lewis Center played an integral role in bringing Los Angeles to the forefront of regional studies with efforts such as Waldinger’s book “Ethnic Los Angeles.” Today, it’s hard to imagine a discussion of immigration and foreign-born individuals without considering L.A.

Waldinger said the center’s early research has transformed California policy. Although immigration policy is a federal issue, immigrant policy can be local, he noted, pointing to state measures that have aided California’s immigrant population.

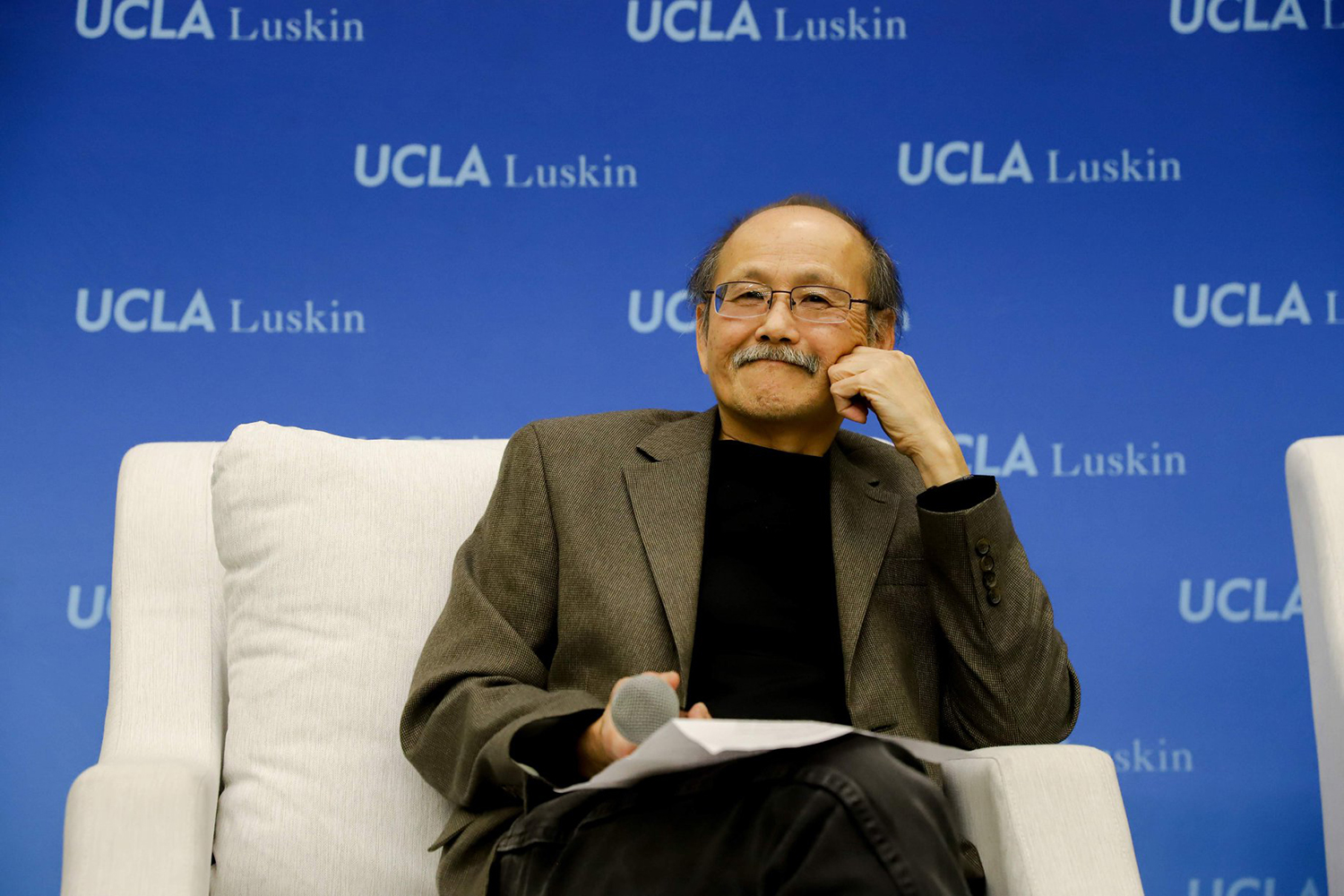

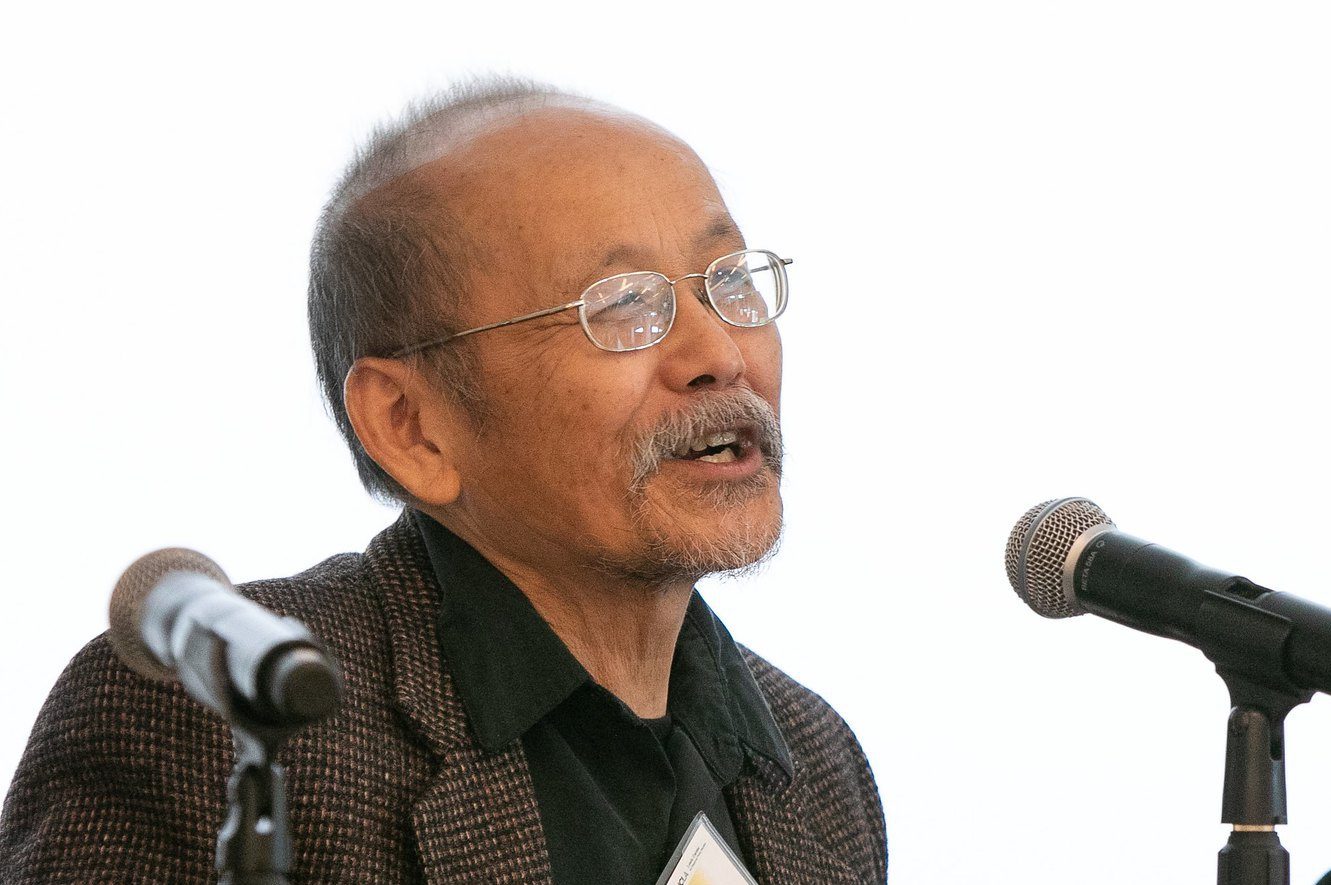

Ong, the center’s third director, continued the multidisciplinary tradition of the Lewis Center and collaborated with scholars in UCLA Luskin Social Welfare and the natural sciences. As director, he published a seminal report on the undercounting of low-income people and communities of color in the 2000 Census.

Ong’s work also highlighted a core strength of the Lewis Center — its focus on addressing social justice issues for marginalized communities. He said the center also partnered with the County of Los Angeles and L.A. Metro to understand the transit needs of underserved communities.

DeShazo oversaw the Lewis Center during a time when its focus turned to environmental issues. In 2006, California passed the Global Warming Solutions Act (AB 32), promoting ambitious climate solutions that even some legislators doubted could be achieved.

“Those were the days we didn’t even know where greenhouse gases were coming from,” DeShazo remembered. The first step was to identify sources and then to identify solutions to reduce emissions, including electric vehicles, rooftop solar energy and energy-efficient technology.

“Everything that we have today is what people thought was impossible to accomplish. The groundwork for that was laid in the 2006-2012 period,” DeShazo said.

The Lewis Center has also contributed to environmental justice scholarship, especially the designations of disadvantaged communities as a result of identifying where emissions were coming from and where populations vulnerable to those emissions are living.

Taylor next put the focus on housing affordability and transportation in light of large investments in public transit like Measure R, a sales tax that is expected to raise $40 billion over 30 years.

He said the center’s regional lens has a built-in advantage when it comes to studying housing affordability, transportation and access, which play out across a diverse geography.

Taylor’s tenure also overlapped with his role as chair of UCLA Luskin Urban Planning. It was a position that helped him to advocate for the addition of faculty members and scholars who could tackle these regional priorities.

“Housing affordability was not my area of research,” Taylor said. “All I did was try to support and catalyze the intellectual leaders that are helping shape the important debates on this.”

A Legacy of Leadership

Acting as a consistent bridge to marginalized voices, the Lewis Center’s former directors see scholarship and professional development as their enduring legacy. Many onetime students have gone on to become academic leaders in their own right.

“I’m honored to follow in those footsteps,” said Blumenberg MA UP ’90, Ph.D. ’95. She became director in 2018 and has focused on how Angelenos live, move and work in L.A., with a particular interest in pathways out of poverty. The center recently launched the Randall Lewis Housing Initiative.

Has Los Angeles made progress over the last 30 years?

The answer is mixed, Ong said. A commitment to climate change initiatives and equity are highlights, but income inequality and social justice remain daunting issues.

“I’m proud of the fact that the Lewis Center continues to look at issues of inequality,” Ong said. “We’re dedicated to doing the research to find solutions, but it’s like swimming upstream.”

Still, Ong remains hopeful: “I know enough about [Blumenberg’s] history that there will continue to be a commitment from the Lewis Center to accomplish things that will bend us towards justice.”