The Power of Lived Experiences Three alumni share the personal stories that impact their policy efforts on homelessness — ‘the greatest moral and humanitarian crisis of our lifetime’

By Les Dunseith

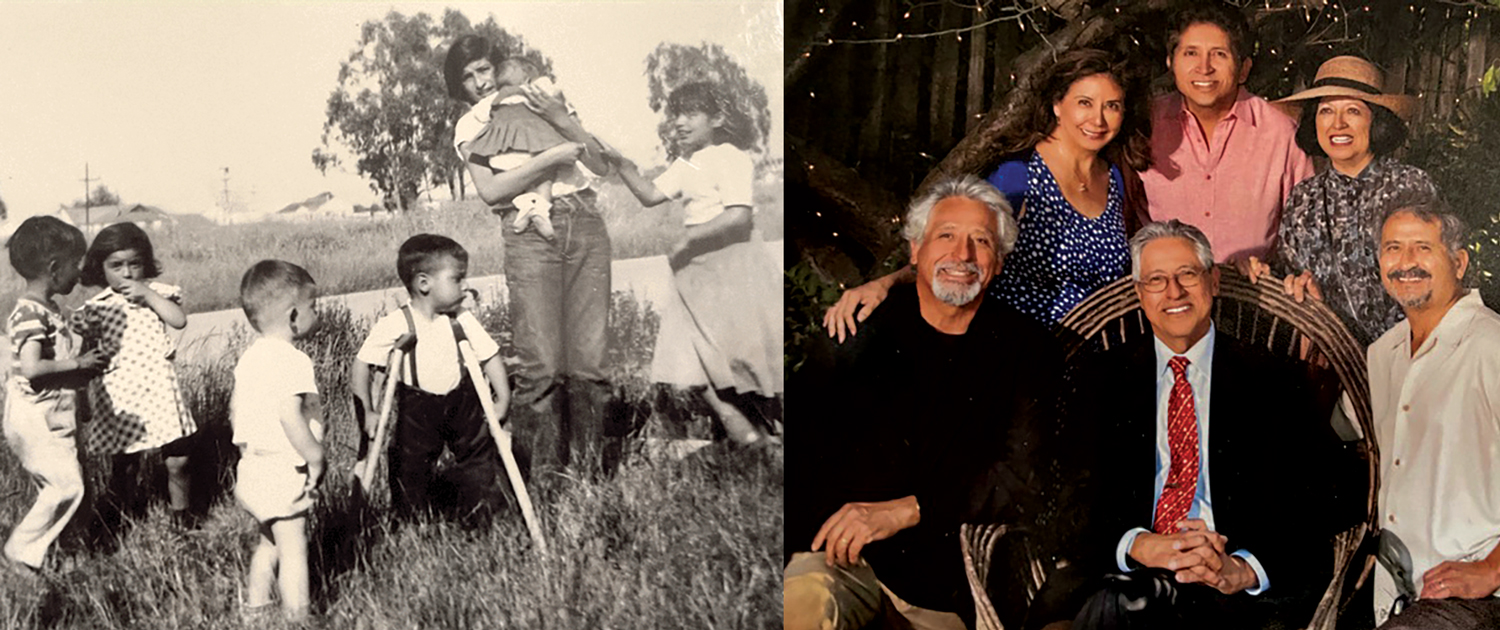

Lourdes Castro Ramírez entered college as one of nine children from a tight-knit working-class family that had migrated from Mexico when she was 4. She had no idea how that background would guide her career as a policymaker focusing on housing affordability.

“As a first-generation college graduate, I did not intend to get into this field,” Castro Ramírez recalled March 7 during a Meyer and Renee Luskin Lecture Series event that included State Sen. Caroline Menjivar MSW ’18 and Assemblymember Isaac Bryan MPP ’18. “In fact, I didn’t even know that this field existed.”

Now Castro Ramírez is the point person for Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass on housing and homelessness, working on an issue that has reached crisis proportions after too little national policy attention for decades.

“I do feel that there is hope. We are now finally seeing housing policy in action, getting the attention that it requires,” the 1996 UCLA urban planning master’s graduate told faculty, students, alumni and others at the Luskin Conference Center.

“Homelessness is the greatest moral and humanitarian crisis of our lifetime,” Bryan said. “We’re at a crisis position even though [California has] more billionaires than anywhere in the world. But that is the Los Angeles that we have created.

“And it didn’t just happen. I don’t want to believe it was on purpose because it would be too painful to believe that somebody wanted tens of thousands of poor and disproportionately Black people sleeping on our streets,” he said. “I don’t want to believe that it was intentional. But neglect isn’t an excuse to not make it right.”

Bryan represents a district near the 405 and 10 freeways mostly to the east and south of UCLA that includes some of the L.A.’s wealthiest neighborhoods — and some of its poorest. He talked about the irony of needing to raise money by speaking to rich donors in the mansions of Beverly Hills and then returning to his rented apartment in a modest-but-affordable neighborhood just a few miles away.

He has experienced housing precarity first-hand, including during his UCLA education.

“I remember walking across the stage on graduation day. I was very proud. I was very excited,” Bryan recalled. “And there was a faculty member in the audience who knew that I couldn’t pay my rent that month. And she wrote the personal check to make sure that I could stay afloat till I found a job.”

Bryan was able to get his UCLA degree in part because he received a grant from the David Bohnett Foundation, which seeks to improve society through social activism and since 2007 has been providing awards that include a position in the L.A. Mayor’s Office for three selected fellows. Longtime adjunct instructor and UCLA Luskin Board of Advisors member Michael Fleming is the founding director of the Bohnett Foundation. He served as the moderator for a Q&A with Castro Ramírez, Bryan and Menjivar, who like Bryan is a former Bohnett fellow and a master’s degree recipient from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. All three talked about income disparity and how their personal experiences relate to affordable housing issues in California.

Menjivar said her large family of Salvadoran immigrants struggled to make ends meet while living in one- or two-bedroom apartments in low- to middle-income communities like Tarzana. Her mother worked as a house cleaner.

“I would commute to school and sometimes get a ride from my mom,” Menjivar recalled. “She would drop me off — her firstborn, first-generation student at UCLA, the No. 1 public university in the world — and then she would go down the street to clean a mansion.”

That perspective is never far from her mind.

“Now, I represent 1 million people in the state legislature, looking to bring more affordable housing,” said Menjivar, whose district includes Burbank and many working-class neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley. “So, when [policymakers] talk about eviction protections and housing affordability, I don’t just speak on it. I’ve lived through that.”

Their lived experiences affect the decisions that Menjivar and Bryan are making and the issues they choose to advance as elected officials in Sacramento. Both have been involved in efforts tied to their backgrounds in public policy and social services. (Menjivar noted that, like herself, Mayor Bass was educated as a social worker.)

In prepared remarks that preceded the panel discussion, Castro Ramírez spoke about her fondness for UCLA and why she was happy to accept the speaking invitation.

“Just walking into this space and seeing UCLA in the background, and seeing so many people I know here, just makes me really proud of my parents, where I come from and this university that invested in me,” she told an audience that included current colleagues on the Luskin School’s Board of Advisors.

It was a UCLA professor who first encouraged her to look into affordable housing as a potential career path, she said, and that led to roles as a practitioner and policymaker at the municipal level in Ventura and San Antonio, at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development under the Obama administration, and later in Sacramento as Gov. Gavin Newsom’s secretary of the Business, Consumer Services and Housing Agency.

“And now I’m back in L.A., back to my hometown … and working on the issues that are really important and critical to our city, to our state, and to our country as chief of housing and homelessness solutions,” she said.

Castro Ramírez spoke about harmonizing federal, state and local government efforts, a process that the mayor’s office characterizes as “locking arms” to address the housing crisis.

The overall number of people falling into homelessness continues to outpace the number who are being housed, but this is not because individual efforts have been unsuccessful.

“In fact, there are incredible nonprofit organizations, housing authorities, housing groups who are doing amazing work,” she said, noting that a supportive housing approval process that used to take six months now takes an average of 43 days. Almost 14,000 affordable units have been approved for Los Angeles.

“This is what the intersection of policy and programming implementation looks like, being able to move with a sense of urgency, being able to implement the idea that having a place to call home is fundamental,” Castro Ramírez said.

Public service can be frustrating work, charged with philosophical disagreement and subject to constant second-guessing often motivated by political opportunism. Fleming asked the panel what makes the aggravation worthwhile.

“I want to make my community, my city, my state, my country better. And that is an awesome privilege that I try to never take for granted,” said Bryan, noting that his chief of staff is another Class of 2018 UCLA Luskin graduate, Caleb Rabinowitz. “And when we walk out of the Capitol, we can kind of ask ourselves, ‘Is the state better this week because we were here?’”

Menjivar said she is motivated by her family history.

“My mom came to this country for a better future for her kids not knowing that the future for our family tree would lead from house cleaner to state senator in one generation,” she said.

But there have been hurdles along the way, and that’s also a motivation.

“I was born with what I call the Triple L — a lady, a Latina and a lesbian. So you can imagine I have a handful of stories around discrimination, around facing barriers and overcoming them, and I know that others helped in getting me to the point that I am now.”

Her lived experiences are vital to her success.

“I think about every barrier that I went through to get to this point, every ‘No’ that I got, even when I was running for office. And for every “No’ that I was given, I’m here now to ensure that other people like me don’t get those ‘Nos’ anymore.”

Castro Ramírez said she is grateful to have gone “to an amazing university and to step into a role that I never thought that I was prepared to step into.” Glancing at her fellow alumni, she continued, “And I’ve been able to see the power of our collective ability to make change and to make a difference.”

She paused for a moment, then spoke again, softly.

“I guess the last thing — and the reason I’m hesitating is because, you know, this is a very personal reason for me — I am the mother of three children. I had a son; he was 11 years old when he passed away due to cancer. He was really an incredible, talented individual who craved … leaving his mark in this world. And that didn’t happen.

“And I feel like every day that I wake up, every day that I show up to work, show up to address the work that needs doing, I feel like I’m showing up for him.”

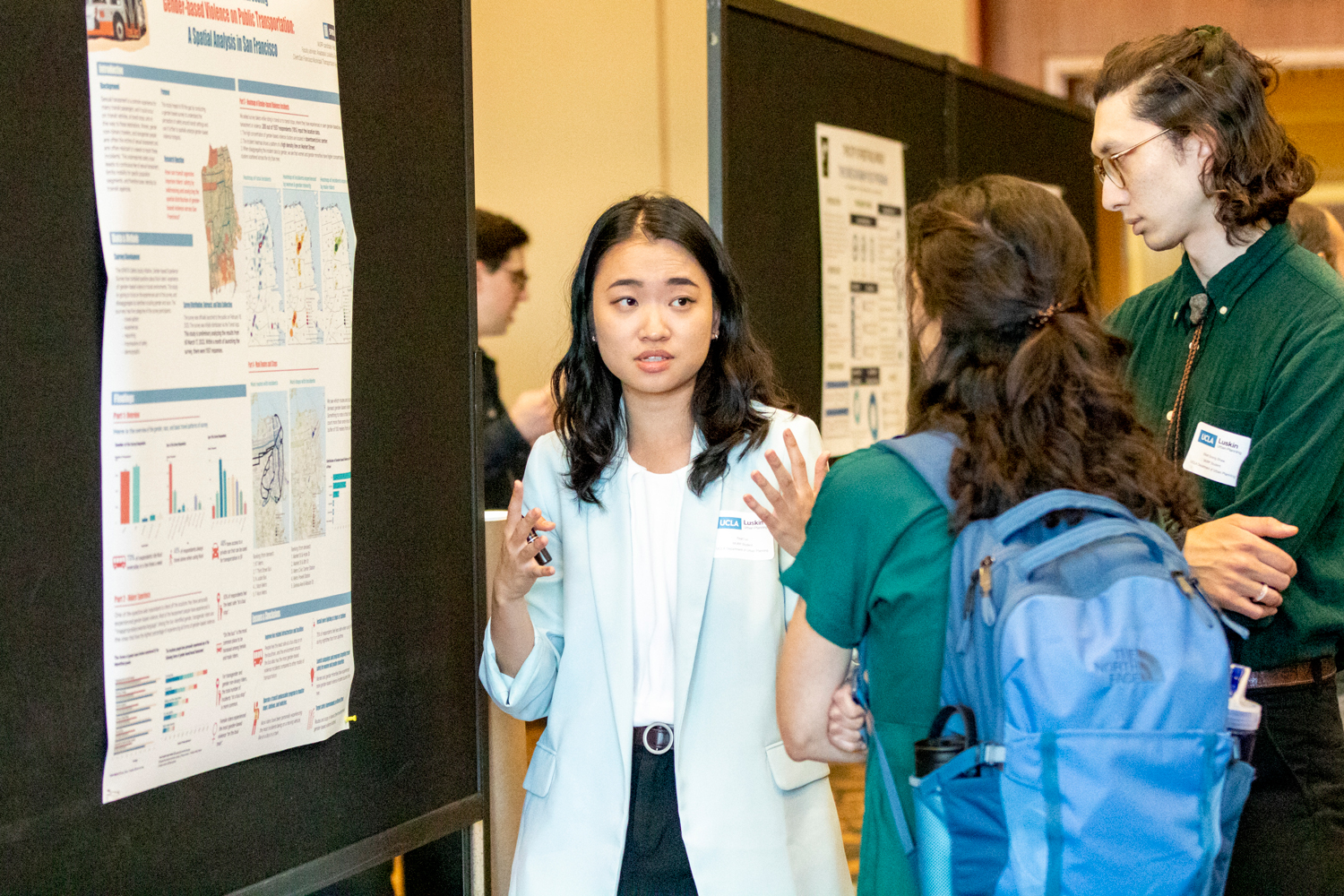

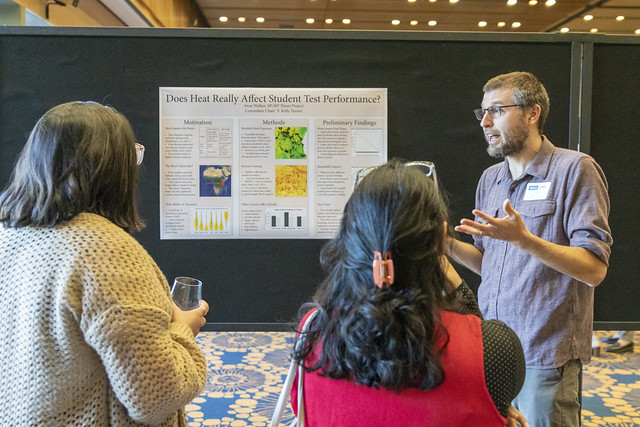

The UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs hosts the Luskin Lecture Series to enhance public discourse on topics relevant to the betterment of society. This presentation was also part of an ongoing series of events in the 2023-24 academic year to commemorate 25 years since the first graduating class from UCLA Luskin Public Policy was sent into the world equipped to make changes for the better.

View photos of the event.

As UCLA Luskin Social Welfare celebrates the 75th anniversary of its founding, Torres-Gil will retire after more than three decades helping to advance the School’s educational mission as a professor of social welfare and public policy. He has served as chair of Social Welfare, associate dean and acting dean, as well as founding director of UCLA’s

As UCLA Luskin Social Welfare celebrates the 75th anniversary of its founding, Torres-Gil will retire after more than three decades helping to advance the School’s educational mission as a professor of social welfare and public policy. He has served as chair of Social Welfare, associate dean and acting dean, as well as founding director of UCLA’s

“I think we have to reweave it, reimagine it and remake it to serve with equality, inclusion and humanity,” Mitchell said. “We have got to be as intentional about equity as previous generations have been intentional about exclusion.”

“I think we have to reweave it, reimagine it and remake it to serve with equality, inclusion and humanity,” Mitchell said. “We have got to be as intentional about equity as previous generations have been intentional about exclusion.”