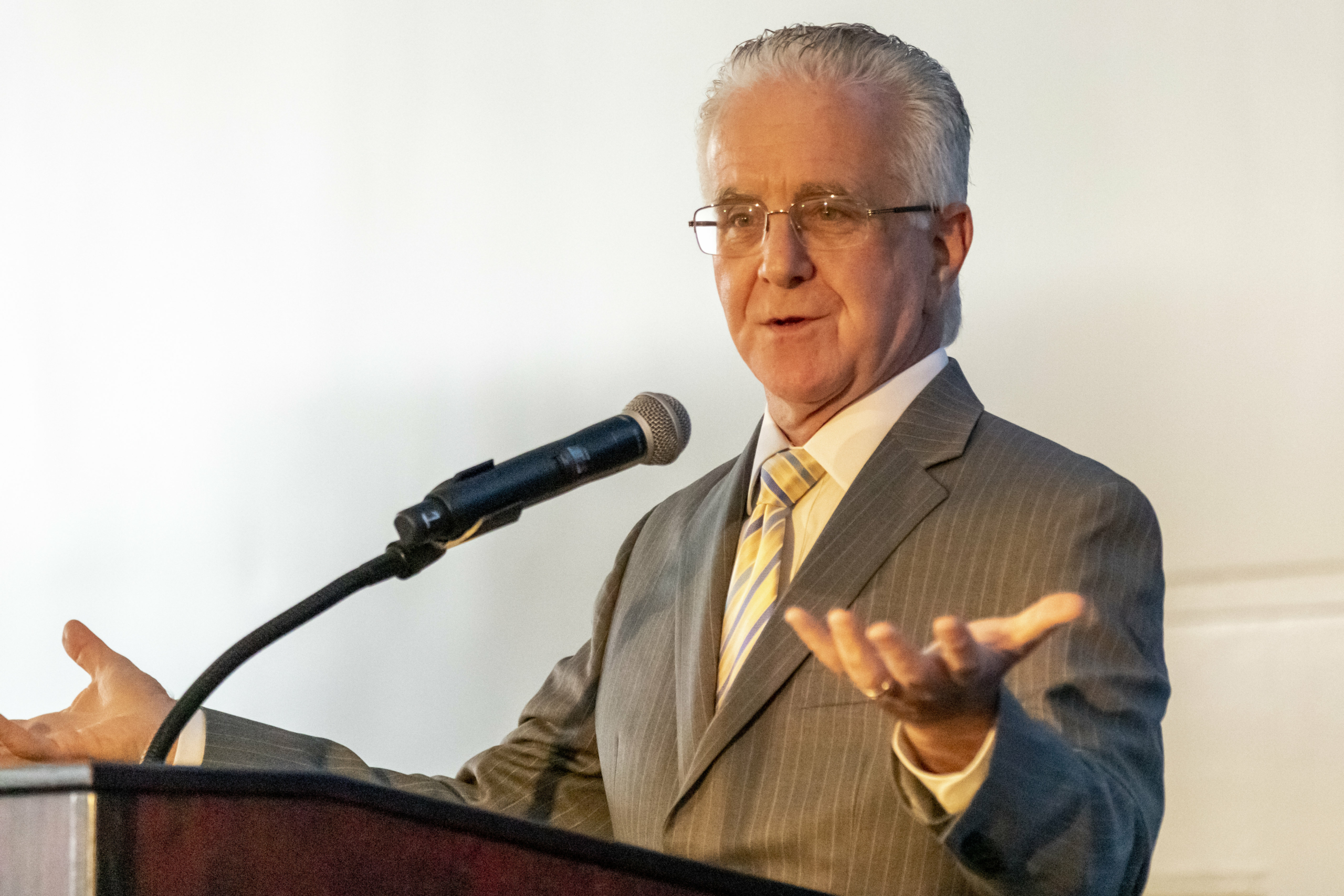

Alumnus Looks Back on UCLA Social Welfare in the Turbulent 1960s Mickey Weinberg MSW '69 on his education and career as a grassroots organizer and advocate for the disadvantaged

Mickey Weinberg earned his Master of Social Welfare at UCLA in 1969, a year when the country was divided by war in Vietnam, Richard Nixon arrived in the Oval Office and humans first set foot on the moon. Trained in grassroots organizing, Weinberg was well-positioned to be of service to disadvantaged communities at a turbulent time.

An Ohio native, Weinberg earned his bachelor’s in political science from University of Cincinnati in 1963, then headed to New York’s Columbia University to study law. Realizing this was not his calling, he left Columbia and took a job at Manhattan State Hospital, where he worked for close to two years before returning to University of Cincinnati for graduate courses in poli sci. In the autumn of 1966, he came to UCLA to continue his graduate education, eventually switching to Social Welfare and its program on community organizing.

An Ohio native, Weinberg earned his bachelor’s in political science from University of Cincinnati in 1963, then headed to New York’s Columbia University to study law. Realizing this was not his calling, he left Columbia and took a job at Manhattan State Hospital, where he worked for close to two years before returning to University of Cincinnati for graduate courses in poli sci. In the autumn of 1966, he came to UCLA to continue his graduate education, eventually switching to Social Welfare and its program on community organizing.

His classmates were an impressive group, Weinberg recalls. They included Maury Samuel, a minister nicknamed Father Sam who had delivered food to distressed neighborhoods during the Watts riots, and June Sale, who introduced Weinberg to historic East Los Angeles and later became prominent in the field of child care services.

Weinberg’s career path led to Los Angeles’ federal veterans affairs hospital, where he spent nearly three decades. He helped many Vietnam veterans secure housing and other services, all the while challenging the medical model of mental health. He has continued this advocacy since his retirement in 2000.

This year, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of social welfare education at UCLA, Professor David Cohen, associate dean of UCLA Luskin, spoke at length with Weinberg to hear about his days as a student in the ’60s and his long career as an organizer and medical social worker. The interview was edited for space and clarity.

On the experiences that drew Weinberg to a career in social work:

As an undergraduate student, I worked in the summers in Cincinnati playgrounds, first as a maintenance man but later as a play leader, as they called it. I recall a lot of Appalachian kids there, they could relate to me, and at the end of the day, when the swimming pools were drained, perhaps for polio reasons, we would sit on the edge of the pool and talk quietly. Cops were often called to the playgrounds because the teenage boys were rowdy, but they were never called to my playground. Later, my work at Manhattan State Hospital changed my life — not only because of the harmful things I saw, but the good things, too.

On his recollections of a boy named Frank, born in Manhattan State Hospital and confined to the hospital grounds after his mother died:

Frank was very upset because he didn’t want to stay there all the time. He wanted to get into Manhattan, but couldn’t because someone had written in his chart that he was homicidal. The reason: He had one possession, a transistor radio, and they took it away from him as punishment and he blew up. I went to the psychiatrist in charge of male patients, and I said “This is a good kid, it can’t be good for him to spend his whole life in this place. What do you think about letting him do what he wants to do?” So we did it. The kid’s going back and forth between the hospital and Manhattan. Very quickly he got a job as a bicycle messenger. He joined a church. They loved him in the church, he got adopted by a family, he could leave the hospital. So what I learned from that as a twenty-something-year-old, is that sometimes the best thing you can do for hospital patients is get off their back.

On his education in grassroots organizing at UCLA Social Welfare:

There were just six of us in that concentration, and I recall that we were very separate from the rest of the students. Our grassroots group met almost exclusively with Warren Haggstrom. He was an incredible teacher. The way he talked about power, the simple and clear language that he used, was inspiring. Part of his pitch was not only about the use of power, but how to talk to people. But we didn’t just talk. He took us out to Delano, where he introduced us to farm workers and their organizer Cesar Chavez. I recall that we were frisked and patted down before meeting Chavez, indicating the nature of the situation.

On a student walkout organized by Weinberg and his classmates:

We wanted some changes, so we organized a walkout of all the students. Haggstrom told us later that he thought we would never do it, couldn’t pull it off. But it was he who gave us the tools and confidence to make it happen. What we wanted was more minority students admitted. There was only one Black student in our grassroots major. We also wanted curriculum change. My friend and classmate Jack Carney and I were on the phone every night to pull it off. I remember that we wanted to make sure that older students in the program, there were a few, would be on the picket line. We wanted our faculty to notice, we wanted people who walked on campus to notice. One measure of its success was a meeting the faculty had with Black students in the School to discuss increasing minority enrollment, a meeting that was open to everybody.

On his Social Welfare field placements:

My first-year placement was in East L.A. at welfare rights offices. I spoke to a lot of moms, moms of schoolchildren, moms who were worried about drug dealers in their neighborhoods. My second-year field placement was at the Veterans Administration, and it grew out of a summer job when I worked in what they called the domiciliary, where vets lived who had no other place. It was during that summer job that I met George Katz, a psychologist who had supervised psychology students there. He learned of my background working in the state hospital and that I was skeptical of psychiatry, and he took me under his wing. After my placement ended and I graduated, they hired me to organize the people living in board and care homes. Because at that time, we had decided to redefine helping these people, into helping people learn how to help themselves. Essentially, to organize them.

On his work on a grant-funded project to organize residents of board and care homes, many of whom had been labeled mentally ill:

We put a classified ad in the L.A. Times, looking for former psychiatric patients interested in organizing to meet with us. We got a meeting room somewhere in Hollywood, and I recall a woman in that group, very quiet, who hardly ever spoke at meetings. But people thought she was intelligent, and it was suggested she take minutes of meetings. Later, she and her husband had to leave the state, and she approached me and said, “I want you to know that I was planning to commit suicide, and if it hadn’t been for how respectfully and kindly I was treated in these meetings, I would not be alive today.” People can be helped in many ways. Another learning experience for me.

On learning the power of teaching people to advocate for themselves:

At the board and care homes, we organized people to do what they wanted to do — if there was vermin in the board and care homes, if the food was bad. For the first weeks, all I did was sit around, just observing. And you know, they’d come up to me, and say, “What are you doin’ here?” I’d say: “I’m here to help.” This went on for six weeks. They’d come back, insisting, “What d’you want to do?” And me: “Well, what do you want to do?” And they said whatever their problems were, and then I said, “Oh, you want to do it. OK. If you want to do it, help me get the rest of the people who live here together, and we’ll have meetings.” And we had meetings, and what we did was to find ways to have meetings with the ownership, to solve problems. When it was over, some state people researched it and found that the people who were in the organizations were much more confident than those who weren’t, and they were better able to function and solve their own problems. Because that’s what we talked about: how to solve the problems. No talk at all about mental illness or anything. It was just: you have a problem and let’s all figure out a way to resolve it.

As UCLA Luskin Social Welfare celebrates the 75th anniversary of its founding, Torres-Gil will retire after more than three decades helping to advance the School’s educational mission as a professor of social welfare and public policy. He has served as chair of Social Welfare, associate dean and acting dean, as well as founding director of UCLA’s

As UCLA Luskin Social Welfare celebrates the 75th anniversary of its founding, Torres-Gil will retire after more than three decades helping to advance the School’s educational mission as a professor of social welfare and public policy. He has served as chair of Social Welfare, associate dean and acting dean, as well as founding director of UCLA’s