Urban Planning Turns 50 Longtime observers say activist spirit of its 1960s creation still permeates the program

By Les Dunseith

Fifty years ago, moon landings made headlines, flower children flocked to Woodstock, and college campuses across the nation experienced sometimes-violent protest over issues such as the Vietnam War. As the turbulent ’60s gave way to the 1970s, it was a time of change. Unrest. New ideas.

And amid that backdrop of societal upheaval, the study of urban planning got its start at UCLA.

Donald Shoup, the longtime UCLA professor, was there to see it. Shoup had arrived at UCLA in 1968 as a postdoctoral scholar at the same time as Harvey S. Perloff, the founding dean of the new School of Architecture and Urban Planning, “who was a great figure in urban planning, of course.”

From the beginning, the UCLA planning program under Perloff reflected an activist ethos and a strong interest in equity. “I think that we look very carefully at income distribution and the effects of how any policy would affect lower-income people. We look at how to reverse that pattern,” Shoup said.

Jeffry Carpenter was also studying at UCLA in 1969, and he was among the first group of students to attain a degree in urban planning. “We were supposed to graduate in the summer of ’71. And some of us did,” Carpenter said with a laugh. “And some of us didn’t.”

Carpenter, who would go on to leadership roles as a planner for what was then known as the Southern California Rapid Transit District, the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency and elsewhere, said graduate programs in planning were rare at the time — almost unprecedented.

“The challenge was that in the field, there was a profession. People were selling planning services, and there were planner positions and there were planning consultants, but there weren’t planning degrees,” Carpenter recalled.

When people like him got those first degrees, “the thought was that it would be something really useful. But the challenge was nobody knew exactly what that was,” Carpenter said. “We were — both the faculty and the students — still feeling our way.”

Nowadays, Shoup is a distinguished research professor whose landmark work on parking reform has had broad impact. He left Westwood in the early 1970s to work at the University of Michigan but returned to UCLA to stay in 1974. A year later, Allan Heskin joined him on the urban planning faculty and continued until he retired as a professor in 2001.

Urban planning with a social conscience is important to Heskin.

“I have a history of being an activist,” said Heskin, who oversaw student admissions for some time. “And I always looked for activist students — people who had done things in the world.”

During his two-and-a-half decades at UCLA, faculty and student planners were active in changing the approach of Los Angeles and other local cities to issues related to land use and housing affordability. UCLA scholars were highly influential in Santa Monica political reform, for example, and Heskin remembers that an early graduate, Gary Squier, “almost single-handedly created the housing department” for the city of Los Angeles. Squier, who died in 2012, became the city’s first housing director in 1990.

“Getting the city of L.A. to take responsibility for housing people in Los Angeles was just a major change,” Heskin recalled. “The city’s policy before the UCLA faculty and students did their thing was to say that housing is a federal responsibility, and the city doesn’t do it, and is not concerned!”

Marsha Brown B.A. ’70, who was a manager in the urban planning program at UCLA from 1980 to 2014, said, “There has always been a history of activism.”

The planning faculty and students “are very passionate about what they believe in — whether it’s housing or traffic or diversity or women’s issues. There’s always been a political bent to it,” Brown said. “The goal was always trying to make cities better for the people who live in them.”

Vinit Mukhija, professor and current chair of Urban Planning at UCLA, has been on the faculty since 2001.

He thinks a willingness to defy expectations has been central to the program’s enduring success.

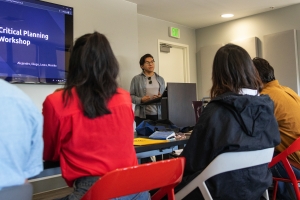

“We never accepted narrow limits of planning or narrow definitions,” he said. “It’s not just land use and transportation and housing. It is much broader than that.”

Somewhat infamously, the program was abruptly split away from architecture in the 1990s and placed into what became the current Luskin School of Public Affairs. But many aspects of today’s UCLA planning program were allowed to blossom naturally over time.

Shoup sees the willingness of faculty to conduct research with students as colleagues as a key to success.

“I think that’s one of the greatest strengths of our program — the collegial relationships between the faculty and the students, and the cooperative learning.”

As faculty have come and gone, the planning program has changed. For instance, transportation planning became more prominent over time. That importance stands to reason in a city known for gridlock, Brown said. “In Los Angeles, transportation is important, you know.”

Another big change has been the gender balance. Shoup gave a recent example — each year he meets with incoming students and tells them why they might want to focus on transportation planning. In his most-recent meeting, “there were 17 women and one man. The complaint at one time was that there were very few women in transportation. So society has changed.”

And the program itself continues to evolve. In time for the 50th anniversary celebration in May 2020, Mukhija said an expanded partnership with Sciences Po in Paris will have been approved. It will offer dual degrees from both universities in a two-year course of study.

Carpenter, who was there in the beginning, thinks future success in urban planning and society as a whole will hinge on continuing to foster the intellectual curiosity of young people.

“The faculty of the school have a very keen appreciation of the powers of perception and understanding, and more particularly also realizing they need to prepare the students to be effective and assume a role and to grow in that role,” he said. “That’s a very encouraging development.”