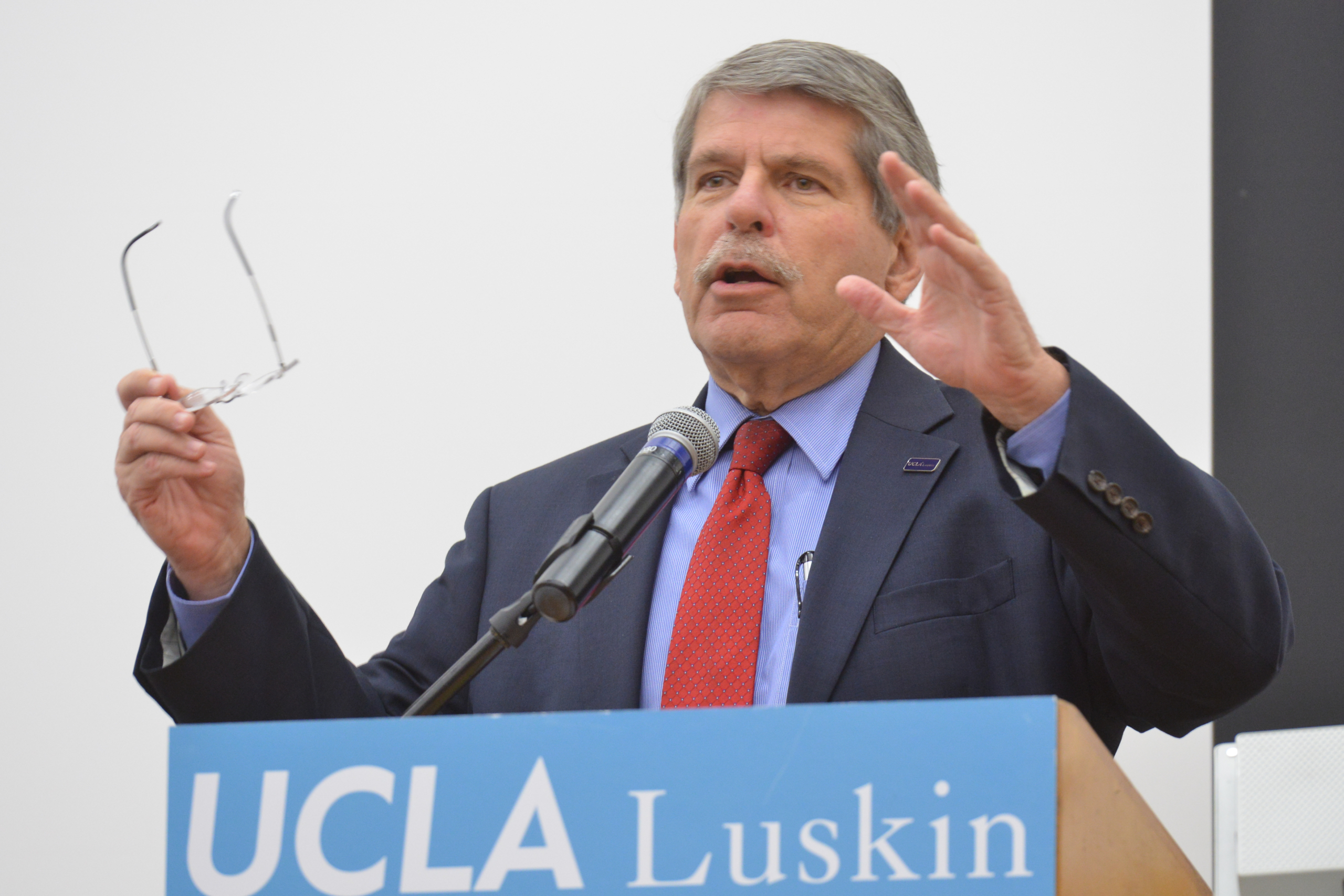

Zev: Legendary L.A. Politico Retires From UCLA Luskin Faculty Yaroslavsky used his real-world experience grappling with the region's knottiest problems to teach and mentor UCLA Luskin students

By Jean Merl

“‘Is it my imagination, or has the homeless situation gotten better around here?’” Yaroslavsky recalled the man asking.

“It’s not your imagination,” Yaroslavsky responded, adding details about at least two area homeless encampments that were cleared when their inhabitants had been housed and offered services under Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program.

“It took time, but they housed them,” Yaroslavsky, 75, said in a far-ranging interview as he prepared to retire this spring from his second career, teaching at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs. “They didn’t just sweep them to another street. They housed them. It’s not easy, but you can do it.”

Yaroslavsky knows his subject. He served nearly four decades as an elected official: on the Los Angeles City Council from 1975 to 1994, when he was elected to the county Board of Supervisors. Term limits required him to retire from that post in 2014. Until then, he had wrestled with — and helped shape responses to — nearly every major issue in the region: health care, land development, open space preservation, police reform, public transportation, cultural development. And homelessness.

Soon after leaving the Board of Supervisors, Yaroslavsky was invited to return to UCLA, where he had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees before leaving a doctoral program to pursue a calling to social activism and politics. He eschewed a common path for retiring politicians — a corporate position or a lobbying or consulting gig — in favor of joining his alma mater, a public university where he could continue his life of service.

“I wanted to bring a real-world perspective to students,” he said. “And I wanted to learn from them.”

From elected office to academia

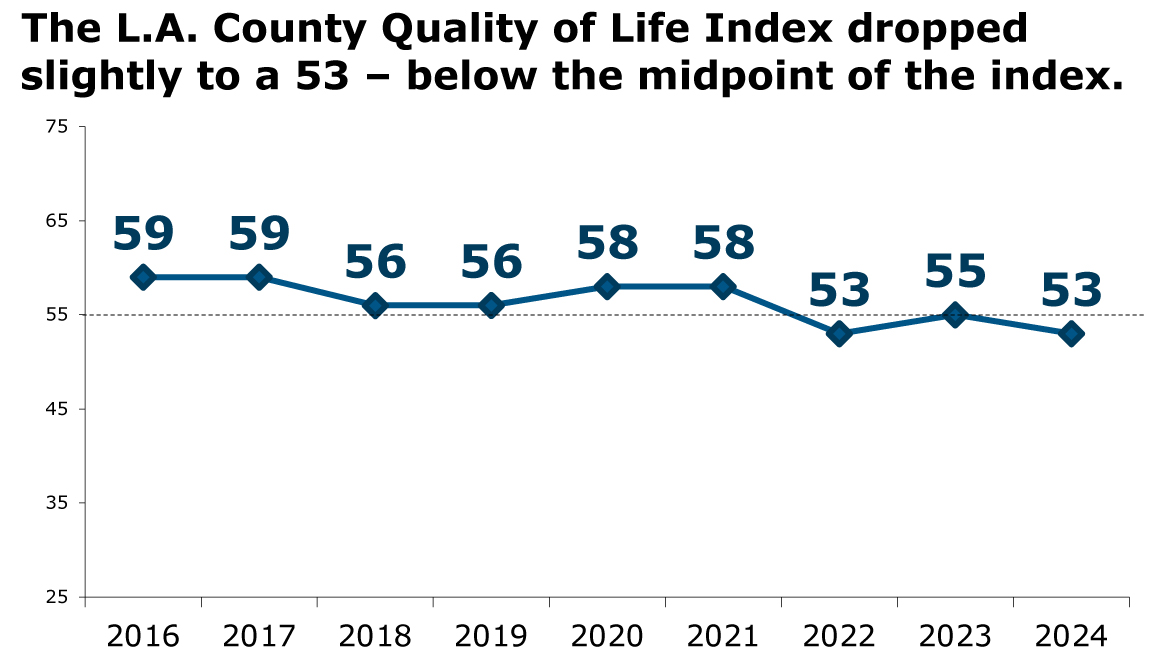

Yaroslavsky’s decade at the Luskin School has placed him squarely at the intersection of public policy and academia. He has taught classes on public policy and directed the Los Angeles Initiative, which conducts the Quality of Life Index, an annual survey of county residents’ satisfaction levels in several categories, including housing costs and homelessness.

He has helped steer bright young students into careers in public service, including Assemblyman Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles). In the spring of 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 lockdowns, he turned his class into a crash course in crisis management by inviting various public officials to talk — via Zoom — about how they were responding to the pandemic.

Although academics and politicians often don’t speak the same language, Yaroslavsky said it is important that they listen to and learn from one another.

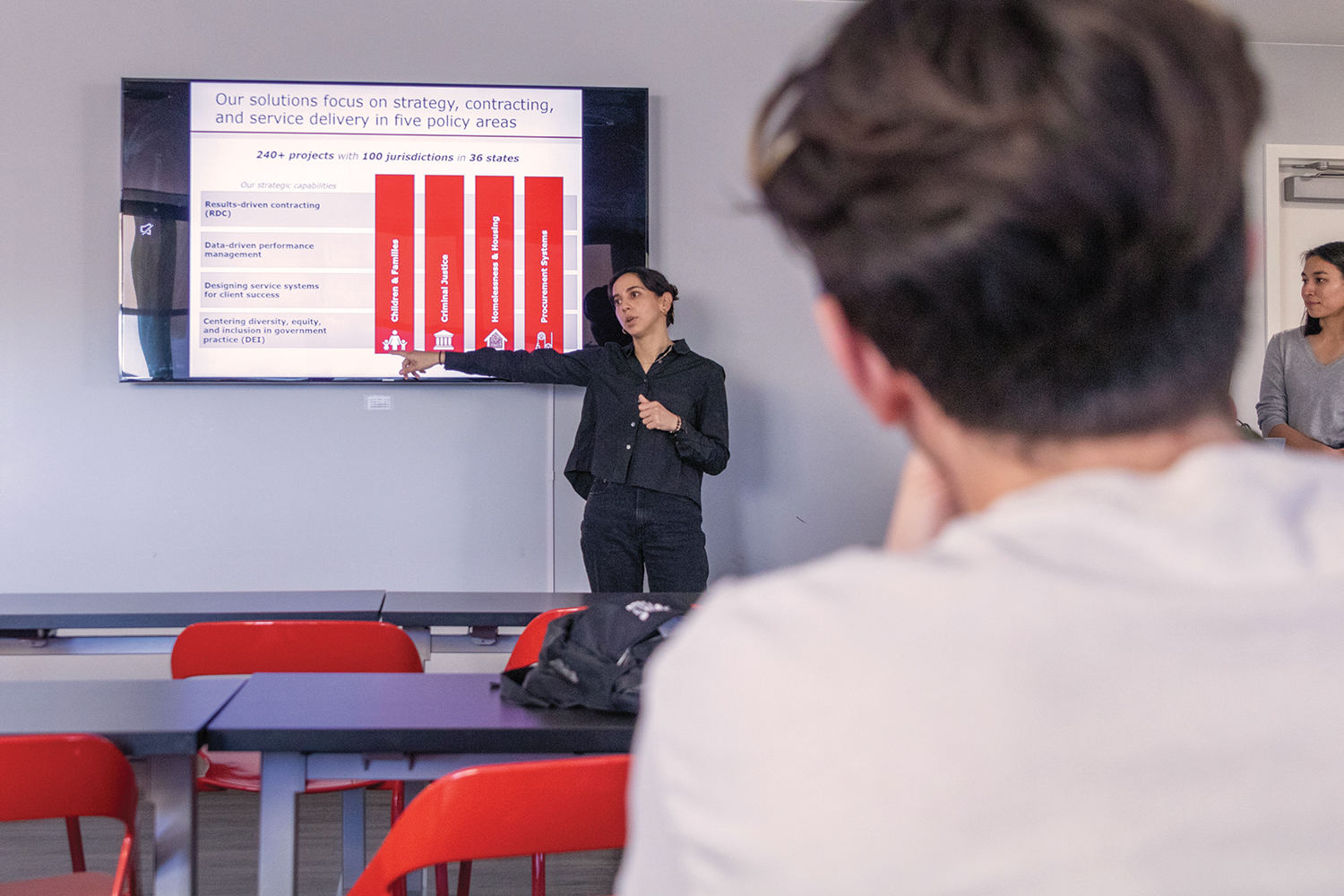

“I do think there is a functional role between academia and government,” he said, noting that think tanks and researchers provide data and reports for policymakers to use in their attempts to find solutions to pressing problems. “It’s important,” he adds, “for academics to understand the pressure politicians are under from constituents and for politicians to know what the facts are.”

Paying attention to the research helps policymakers find solutions and avoid mistakes. “We can’t live without it,” he said.

A history of homelessness

In his role as an academic, Yaroslavsky was one of the authors of a comprehensive study of homelessness in the region, published in 2021 by the Luskin Center for History and Policy. “The Making of a Crisis: A History of Homelessness in Los Angeles” detailed some 120 years of ebbs and flows in the problem, including causes and recommendations.

Earlier, during his time as a county supervisor, Yaroslavsky led an effort to take a comprehensive approach to homelessness, a problem he compares to a Rubik’s Cube — a complicated puzzle that can’t be solved quickly or easily.

In 2007, he spearheaded Project 50, a two-year county pilot project that focused on Skid Row people who were deemed the most vulnerable. The project got them into housing and offered them services to help with the issues that had caused them to be homeless, including addiction and mental health problems. It was based on a successful program in New York City, and it pioneered what is now the standard thinking about ways to combat homelessness — first, provide a home, then address underlying problems to keep people from falling back into life on the streets. The process can be costly and time-consuming, and its success depends in part on removing such stumbling blocks as housing costs, racial discrimination and poor education. But advocates of this approach say the social and financial costs of not solving what has become a crisis are much higher.

For years, Yaroslavsky said, he had behaved like most other politicians. Stay away from homelessness, was the standard political advice, because it’s intractable and costly and you will be branded a failure if your efforts fall short. And it was easier back then to ignore homelessness because it was largely confined to Skid Row and not the crisis that has spread throughout many communities and spilled into pricy, middle-class neighborhoods today.

He said this began to change in 2002, when his daughter, then in graduate school and living in the Bay Area, urged him to pay attention to the issue. He hired a deputy to work on homelessness in 2005. She told him about a pioneering “housing first” program in New York City. On a visit there to attend his son’s law school graduation in 2007, Yaroslavsky toured the program, Common Ground, based in the converted Times Square Hotel, and met with its founder. He pushed for something similar in Los Angeles.

Project 50 worked well for a time. Clients stayed housed and accepted support services, and budget officials found the costs were more than made up by the savings in emergency room visits, arrests and other consequences of life on the streets. A county analysis showed the program cost $2.2 million but saved $2.4 million. As the pilot program was nearing its end in 2009, Yaroslavsky proposed extending and expanding it to 500, then to 5,000, taking it countywide. But he couldn’t get a second from any of the other four supervisors. Yaroslavsky put smaller projects based on the Project 50 model into his own district, but the countywide version died.

Since then, homelessness has exploded into a region-wide crisis that no longer can be ignored, Yaroslavsky said, lamenting that the failure to expand Project 50 in 2009 “basically cost us almost a decade” in solving the problem.

In 2016, voters in the city of Los Angeles approved Proposition HHH, a $1.2 billion bond measure for permanent supportive housing, and the following year, county voters approved Measure H, which enacted a 1⁄4-cent increase on the sales tax for 10 years to alleviate homelessness. Bass won the mayor’s office in November 2022 after a campaign that centered around combating homelessness. Her first official act was to declare a state of emergency because of homelessness. County supervisors followed suit a month later.

Reflections on service and politics

Yaroslavsky, in his 2023 memoir, “Zev’s Los Angeles: From Boyle Heights to the Halls of Power,” called homelessness “the moral challenge of our time” and outlined ways to meet it. His experiences naturally have informed his views on Bass’ attempts. He gives her high marks while acknowledging there is still a long way to go. Other circumstances, ranging from income disparity to the lack of an elected executive in the power-diffused county, also pose considerable obstacles, he added.

A Los Angeles Times analysis of Bass’ program late last year found significant progress in her goal to find shelter for those living on the streets and clear the encampments that had sprung up along public rights of way. But the campaign to find or build permanent affordable housing remained a tough challenge. Bass called improving the system of support services, including substance addiction treatment, a “top, top issue” as the program headed into its second year.

Yaroslavsky praised Bass for her comprehensive approach and willingness to put herself in charge of the program and accept responsibility for it.

“I’m a cheerleader for her,” Yaroslavsky said. “I think she’s doing the right thing.”

But he’s realistic, too. “I’ve said from the start that [homelessness] was not created overnight and it’s not going to be solved overnight. But she’s making progress, and she has created a sense of possibility and is publicly committed to solving the problem.”

Bass also is well suited to the task because of her collaborative manner and her background as a physician’s assistant and community activist before being elected to the state Assembly and then Congress, Yaroslavsky said. He also touted her commitment to Los Angeles.

“She has made it clear she is not interested” in running for another office and probably has eight years to work on the issue, said Yaroslavsky, who expects Bass will serve a second term.

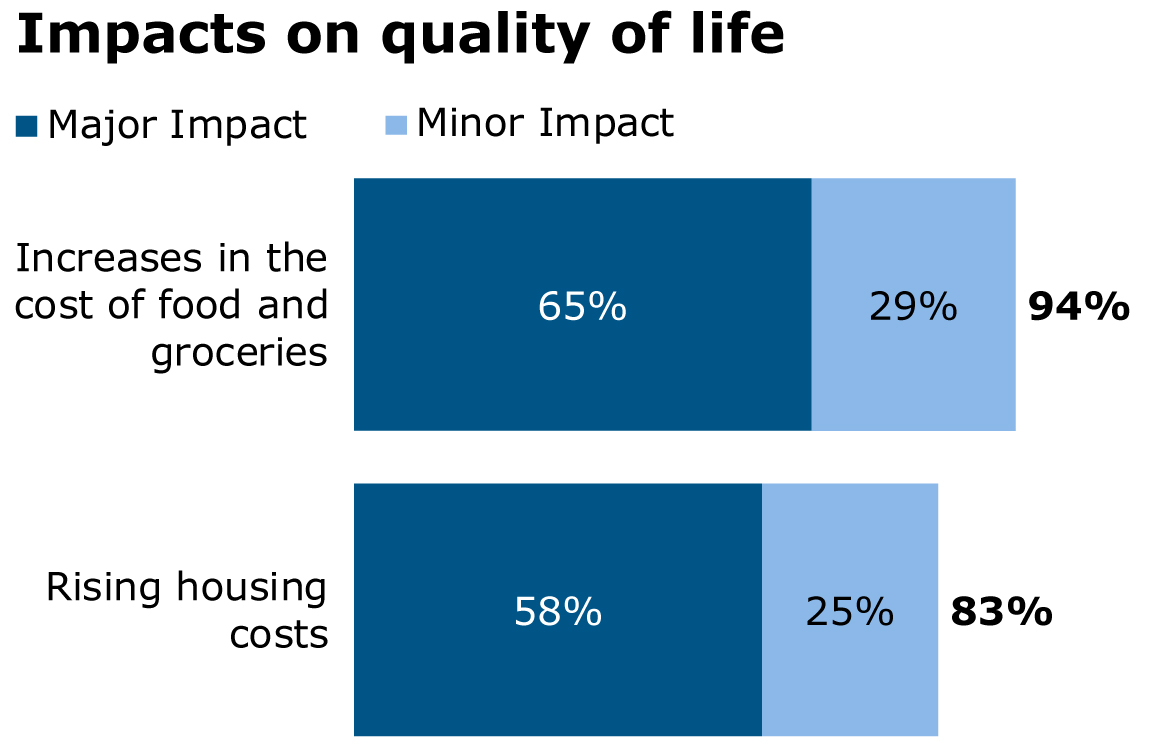

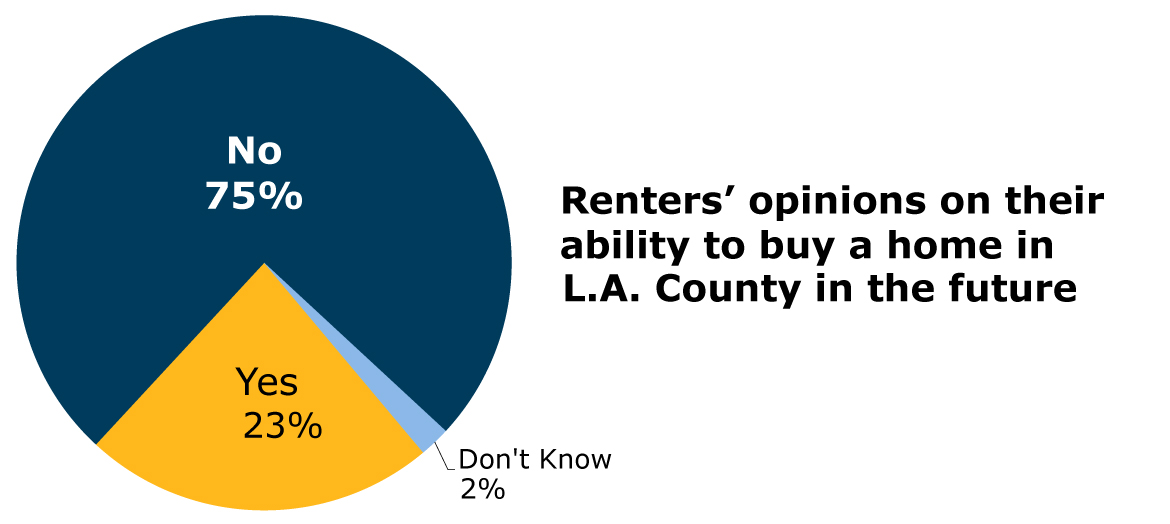

But one of the toughest obstacles to overcoming the problem is an acute shortage of affordable housing.

Increasingly, people are at risk of falling into homelessness, not because they are drug or alcohol abusers or mentally ill, but because they can no longer afford their rent on the wages they earn, Yaroslavsky said. Remedying that will take government intervention, including but not limited to housing subsidies, so that “the people who provide the backbone of the labor market here can afford to live here and not be forced out onto the street” where they eventually develop other problems.

“There’s a structural inequity in our housing economy that creates this homelessness problem,” Yaroslavsky said, “and we’ve got to deal with it.”