By Les Dunseith and Stan Paul

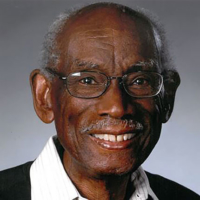

Longtime UCLA Luskin staff member VC Powe, executive director of external programs and career services, died Sept. 16 following complications from a serious illness. She was 66.

Powe BA ’75, MBA ’77 joined the School in 1998 and served in a variety of roles over the years, including director of alumni and government relations. From 1990-97, she worked for the UCLA Alumni Association. Powe also was an adjunct faculty member at Los Angeles City College, where she taught marketing and management.

At the time of her death, Powe, a longtime Culver City resident who was born in Los Angeles, oversaw counseling, internships and fellowships, plus the Bohnett Fellows and Senior Fellows programs, at the Luskin School. Powe, who was widely known on campus simply as VC, was instrumental in developing deep ties to civic leaders.

“VC Powe was a powerful advocate for the Luskin School, its students and alumni,” Dean Gary Segura said. “She worked tirelessly to draw attention to our excellent students, and she never stopped trying to expand opportunities for them to partner with leading members of the Los Angeles community.”

Segura noted that her work with the Luskin Senior Fellows program connected UCLA Luskin students with elected officials, CEOs and the leaders of nonprofit, educational and philanthropic organizations.

“She paved the pathways for more careers in public affairs than we can count. The Luskin School of Public Affairs lost a bit of its heart this week,” Segura said. “VC will be deeply missed.”

Powe’s death was unrelated to COVID-19. Angelus Funeral Home in Los Angeles made arrangements amid the ongoing pandemic for an Oct. 6 viewing, where friends and family paid their respects.

In lieu of flowers, the family asks that any gifts in VC’s honor be made to the VC Powe Memorial Fund, which will support UCLA Luskin-wide fellowships, Career Services and the Senior Fellows program. Gifts can also be made by check payable to the UCLA Foundation. Please include “Fund #14300” in the memo field and mail to the UCLA Foundation, PO Box 7145, Pasadena, CA 91109-9903.

Anyone wishing to send cards and other non-perishable items in her memory can address them to VC Powe’s family in care of the Luskin School of Public Affairs, 337 Charles E. Young Drive East, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1656. Please note that on-campus mail delivery is only available via the U.S. Post Office at this time.

A Luskin School memorial will be announced at a later date.

In recognition of her role strengthening civic life in the region, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors announced that it will adjourn in her honor on Sept. 29. The Los Angeles City Council will also adjourn in her honor that day.

Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, who has longstanding ties to the Luskin School’s leadership programs, called Powe the “perfect combination of supreme competence, kindness and empathy.”

“VC advocated tirelessly for students and worked to help so many individually,” Kuehl said. “When I was lucky enough to serve as a Regents’ professor, I would have been completely lost without her generous time. She will be deeply missed.”

Associate Dean Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, distinguished professor of urban planning, noted Powe’s contributions to vital programs such as Senior Fellows and Luskin City Hall Day and her guidance in helping students start their careers.

“It is so hard to imagine our Luskin School without VC. She was the nicest, kindest person, and utterly committed to our school and its alums,” Loukaitou-Sideris said. “She did her work with tremendous professionalism and grace, and always with a smile on her face.”

Loukaitou-Sideris added that Powe’s longtime role at the annual commencement was especially memorable.

“I will always remember VC, hidden from the large crowds, steadily guiding us toward one more commencement, orchestrated to perfection,” Loukaitou-Sideris said.

Powe’s involvement in commencement was also a fond memory for Bill Parent, who recently retired from the Luskin School after serving as an instructor and member of the staff, where he worked alongside Powe for many years.

“My favorite mental image of VC Powe will forever be her standing front and center on the Royce Hall stage at the very end of commencement, smiling radiantly, her arms raised to signal the graduates to rise and go take on the world,” Parent recalled.

Powe’s enthusiastic guidance of UCLA Luskin students and alumni is well-known, but she was equally supportive of staff members such as Caroline Lee, who joined the Luskin School in July 2019 as a career counselor.

“VC was the most amazing mentor and boss,” said Lee, the assistant director of career services. “She is the reason that I felt so comfortable moving across the country to begin a new chapter in my life. She had the unique quality to make people feel at ease and always welcome.”

Lee continued: “I have never seen someone more dedicated to the success of students.”

Her contributions were many, but Powe’s success with the Senior Fellows program stands out to many as a signature accomplishment. Before she took over, Parent recalled, the fledgling Senior Fellows program was “pretty weak tea,” but that did not deter Powe.

“Year-by-year, fellow-by-fellow, student-by-student, event-by-event, VC nurtured the program into a rewarding honor for scores of fellows and hundreds of students, a centerpiece of engagement for the Luskin School and UCLA in the world of public leadership,” Parent said.

Past and present fellows include elected officials, corporate CEOs, government leaders, entrepreneurs, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists, prominent educators and numerous public servants with ties to the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors.

Powe was adept at matching the expectations of students to what fellows could reasonably offer as mentors, then maintaining contact and paying attention to the details to make things work, Parent said. This approach led to similar success with the Bohnett Fellows program and a wide range of internship programs under Powe’s guidance.

“Near as I could tell, VC’s strongest faith was in the power of education — as a teacher, an administrator, and as a lifelong student of management and leadership,” Parent said. “She believed in UCLA. She believed in the Luskin School and the missions of our three graduate departments. In other words, she believed deeply in us. She dedicated her career, as a vocation, to helping every one of us succeed.”

Powe was also known as someone who went out of her way to welcome new additions to the Luskin School.

“When I first came back to UCLA in 2015, one of the first people who took me under her wing was VC,” recalled longtime elected official Zev Yaroslavsky, a UCLA alumnus who is now director of the Los Angeles Initiative at the Luskin School. “Her engaging smile, understated demeanor, intense commitment to our students, soothing voice, and total embrace of me let me know that I was back home.”

Yaroslavsky recalled that during his time as a public official he came to know Powe as UCLA Luskin’s emissary.

“She came to meetings in my office, asked for advice on how to place more students in jobs, and proselytized me on the great work being done at Luskin,” Yaroslavsky said of Powe’s relentless efforts to advance the School and its students. “She was preaching to the converted.”

Former colleagues across the UCLA campus recalled some of Powe’s other contributions. Keith Parker, a former assistant vice chancellor of government and community relations, said Powe was a friend and colleague for more than 25 years.

“She was someone that always offered a smile, extended a helping hand and took a moment to let you know that she cared about you,” Parker said. “I always told her VC stood for ‘Very Caring.’”

In the 1990s, when Powe was working for the UCLA Alumni Association, outreach to alumni of African American descent was a key focus. “She developed a number of successful outreach programs that brought alums back to UCLA as engaged, supportive alumni,” Parker said. “She worked on the initial Summer Youth Employment Program that brought low-income high school students to UCLA for not only employment experiences, but also exposure to the benefits of higher education.”

After she moved over to the Luskin School, Powe was the principal partner with UCLA Government and Community Relations in the annual School of Public Affairs Day at City Hall during which UCLA Luskin graduate students visit with the mayor, council members and department heads for the City of Los Angeles.

Those meetings focus on an important issue facing the city each year, and the students subsequently produce a white paper with well-researched recommendations, Parker said. “The City Hall Day programs could not have happened without VC.”

Powe’s career history in the late 1970s and 1980s includes employment at May Co., as well as positions in advertising and marketing at the Los Angeles Times. She worked for five years with Inroads, helping to produce business seminars, and she taught business economics at the junior high school level for two years.

She was a former United Way/Kellogg Training Center certified volunteer trainer, a member of the Southern California Leadership Network and a volunteer for the UCLA Alumni Association’s scholarship selection programs.

She held professional certifications in Organization and Human Resource Development (sponsored by the American Society for Training and Development) and Online Teaching from UCLA Extension.

Powe was preceded in death by her mother, Vivian Carrell (Burbridge) Hines. She is survived by her father, Bolden Eugene Hines; her husband, Keith Powe; and three sisters, Brenda Kelly, Roberta Lecour and La Lita Green.

Friends and former colleagues of VC Powe are encouraged to contribute their reminiscences for an online tribute page by commenting on the UCLA Luskin Facebook page or by emailing news@luskin.ucla.edu.

View a video tribute