Shining a Light on Hidden Corners of Environmental Injustice Catherine Coleman Flowers fights for the health and dignity of rural communities where water and sanitation systems are failing

By Mary Braswell

Catherine Coleman Flowers calls it “America’s dirty secret” — the lack of decent sanitation systems in many rural communities where residents must live alongside their own sewage.

It’s a public health calamity that takes the highest toll on poor people of color, and Flowers has made it her life’s calling to shed light on these appalling conditions found in one of the world’s wealthiest nations.

Her work, which began in Lowndes County, Alabama, where she grew up, has now become a national movement with echoes around the world, vaulting her into the top tiers of environmental advocacy and U.S. policymaking. Flowers shared the triumphs and frustrations of her journey, and the work yet to be done, with a UCLA audience as part of the Meyer and Renee Luskin Lecture Series on April 27.

“Catherine has found that the problems of inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure reach across rural America, including California, and these problems … are tied deeply to systems of racial and class oppression,” said Megan Mullin, professor of public policy and faculty director of the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation, as she introduced Flowers to a packed room at the university’s Kerckhoff Hall.

In addition to founding the nonprofit Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, Flowers has received a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award and serves as vice chair of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. A week before her Luskin Lecture, she introduced President Joe Biden as he signed an executive order making environmental equity a priority of federal agencies.

Flowers works with policymakers, researchers and advocates around the country, earning her a spot on Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in 2023. But she told the UCLA audience, “I’m better being out in the community because that’s where my strength is, to help people tell their stories when they wouldn’t be listened to otherwise. …

“Who wants to talk about sewage coming back into your home? Most people won’t do that,” she said. “But now we have to because we don’t have a choice.”

‘Is it possible that there could be diseases in the United States that American doctors are not trained to look for? Because we have not even acknowledged that we have a problem of sanitation in this country.’

Flowers told of impoverished rural communities where residents are by law responsible for disposing of their sewage. Some people own septic tanks that have fallen into disrepair, pushing waste back into sinks and bathtubs. Others simply cannot afford the systems and instead pipe their sewage underground or onto nearby land.

At times, those with substandard waste systems are hit with fines or imprisonment in a system that reveals the interplay of economic, health and criminal justice inequities.

The sanitation emergency has been made more acute by climate change, with its flooded coasts and rising water tables, Flowers said. And the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted public health risks that threaten rural and urban areas alike.

“One of the things that COVID has taught us is that we have to deal with these issues or the next disease is not going to come from China and a wet market, it’s going to come from somebody’s wet backyard that has sewage on the ground,” she said.

Flowers told of a rash she developed after being bitten by mosquitos near a pool of untreated sewage. Her doctor and a dermatologist could find no cause and offer no relief, so she contacted an infectious disease expert.

“Is it possible that there could be diseases in the United States that American doctors are not trained to look for?” she asked him. “Because we have not even acknowledged that we have a problem of sanitation in this country.”

The experience led Flowers to partner with researchers on a peer-reviewed study of the health of Lowndes County residents. It revealed that a third of those tested had been infected by hookworm, an intestinal parasite associated with poor sanitation and thought to have been eradicated in the U.S. decades earlier. The findings were covered by media around the world, and the United Nations special rapporteur for extreme poverty and human rights came to Alabama to investigate.

“The people of Lowndes County, by speaking up and telling the truth, have given a lot of other people permission to talk about these problems as well,” Flowers said.

Her Luskin Lecture was followed by a dialogue with Mullin and Joaquin Esquivel, chair of the California State Water Resources Control Board, who shared both his professional expertise and lived experience as a native of the rural Eastern Coachella Valley.

The panel spoke about the key role of research and data in shaping equitable policies, and the new technologies that could lead to solutions in places where water and sanitation infrastructure is failing.

Esquivel described the state’s decision to pay off hundreds of millions of dollars in water bill debt that built up during the pandemic in low-income households. The stakes were too high to ignore, he said.

“That lack of access to sanitation and drinking water could actually create a system where you could lose your house, you could lose your kids if your water is shut off,” Esquivel said. “There are huge consequences for those at the bottom of the system.”

Flowers said her organization is speaking with NASA engineers to determine whether technologies used to create waste management systems in space could inspire new innovations on the ground.

“We decided that we’re not going to just wait on someone to change policy. We’re going to reengineer the septic tank. And we’re looking to collaborate,” she told the UCLA audience.

“We need your ideas. Because this is not just an Alabama problem. It’s a California problem too.”

View photos from the lecture on Flickr.

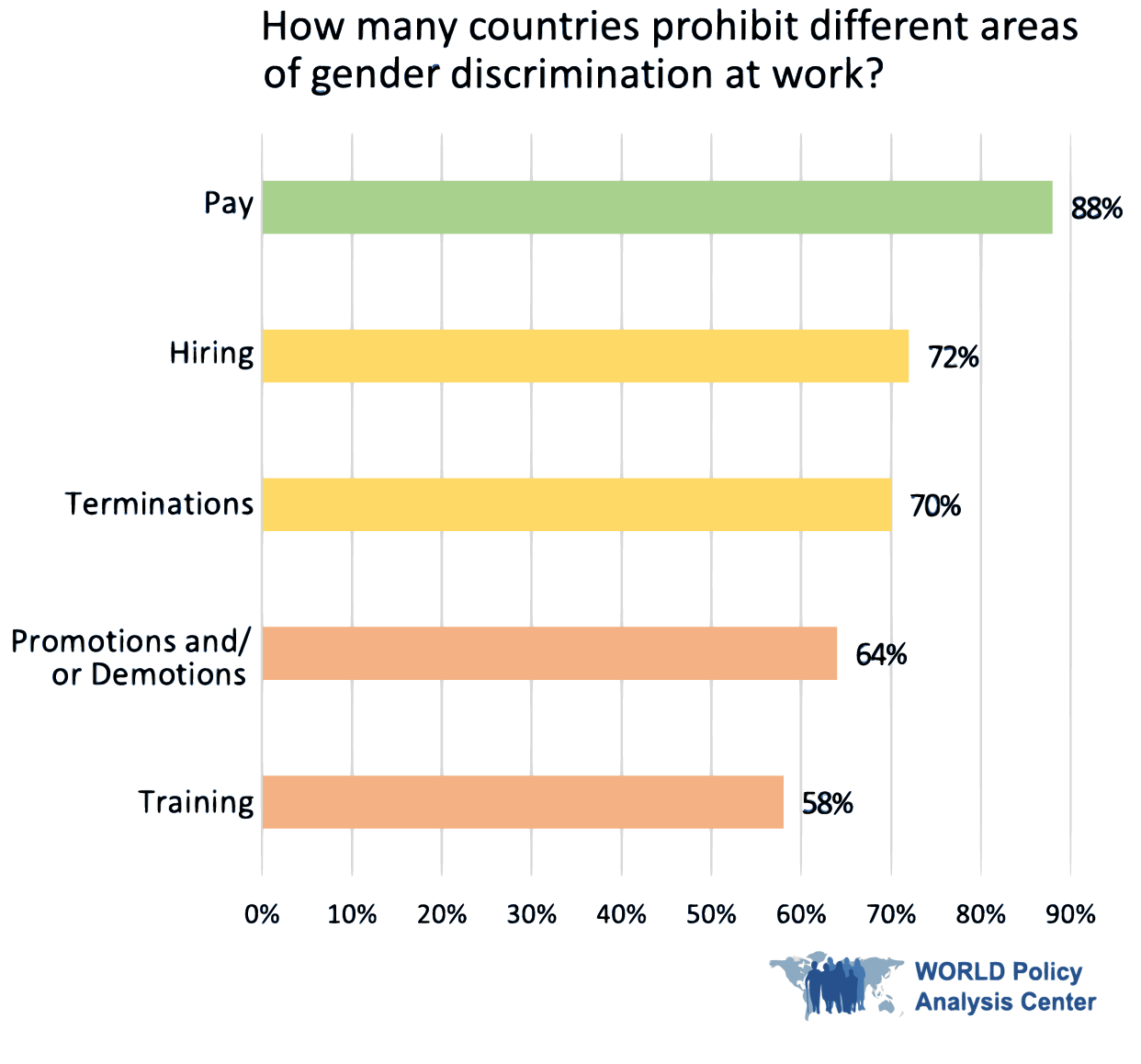

Heymann and her research team analyzed national laws and policies in all 193 countries of the United Nations. Among their findings:

Heymann and her research team analyzed national laws and policies in all 193 countries of the United Nations. Among their findings: