By Stan Paul

John Friedmann, internationally renowned pioneer in urban theory and planning and a central figure in the founding of what is today the Department of Urban Planning at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, died Sunday in Vancouver, B.C., June 11, 2017, following a short illness. He was 91.

Friedmann, who was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1926, came to UCLA in 1969 at the invitation of Harvey S. Perloff, who had recently been appointed founding dean of the School of Architecture and Urban Planning. Perloff, an economist by trade and himself a pioneer and legendary figure in the field of planning, was Friedmann’s dissertation adviser at the University of Chicago. Perloff asked Friedmann to head a new program in urban planning at UCLA.

“Together they brought in a number of ‘big thinkers’ to be the core faculty of the emerging urban planning department, including Ed Soja, Dolores Hayden and Peter Marris,” said Michael Storper, a longtime friend and faculty member in urban planning. Storper, distinguished professor of regional and international development at UCLA Luskin with appointments at the Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) in Paris and the London School of Economics, added that Friedmann and Perloff were among those who published and edited the early fundamental textbooks in the emerging field of regional planning.

“This is a momentous loss,” Storper said. “He brought a real global outlook and sensibility to UCLA.”

Other friends and faculty at UCLA Luskin expressed similar thoughts about Friedmann.

“I consider John Friedmann as the father of our urban planning department — a huge figure whose vision has guided our department’s structure, overall mission and social justice goals,” said Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, associate dean of the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and professor of urban planning. “Aside from being a brilliant scholar, John was an amazing human being.

“I know that I am not the only one who has benefited tremendously from his kindness, mentorship and generosity of spirit,” she said. “John lives in our thoughts and minds. John is UCLA Urban Planning.”

Martin Wachs, distinguished professor of urban planning at UCLA Luskin, agreed.

“While many people contributed to the evolution of urban planning at UCLA, John Friedmann is universally recognized as THE father of the department,” Wachs said. “He was a person of unbounded energy and unlimited curiosity.”

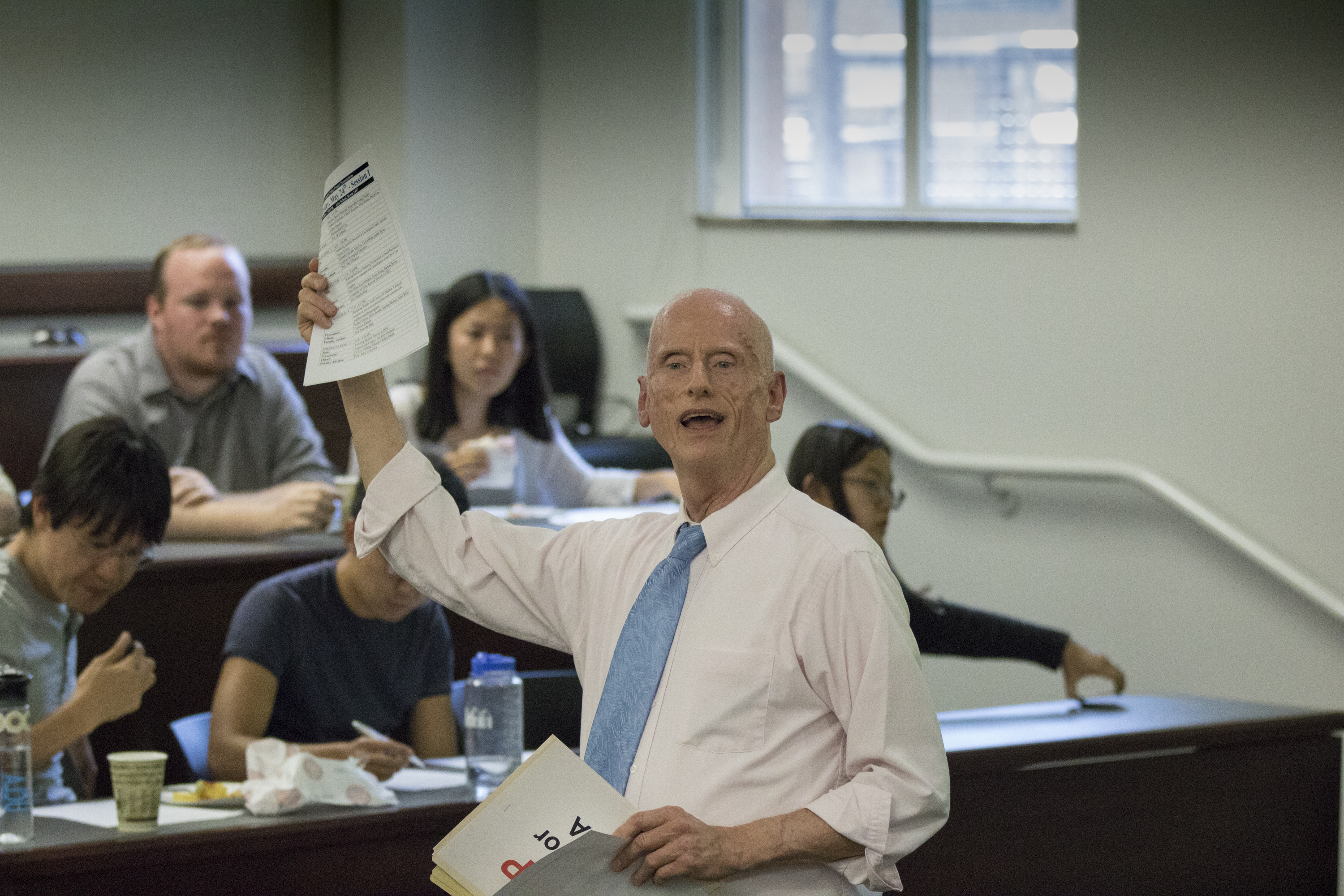

John Friedmann at the 40th anniversary of the Department of Urban Planning, in 2010.

Friedmann, who earned his Ph.D. in 1955 in an interdisciplinary program of research and education in planning at the University of Chicago, served as department chair of the urban planning program for a total of 14 years during his tenure at UCLA. He retired from UCLA in 1996 and lived in Vancouver for many years.

His decades-long career included serving as a member of the U.S. occupation forces at the end of World War II, and his wide-ranging interests took him around the world. After his first 14 years in Vienna, he listed Germany, Brazil, South Korea, Venezuela, Chile, Japan, the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada as stopping points along his journey as a scholar. During his long and life of learning and teaching, he helped establish and maintain an intellectual lineage and link to generations of world-class scholars in the field.

Vinit Mukhija, the current chair of the Department of Urban Planning, said his own dissertation adviser, Bish Sanyal, now at MIT, completed his dissertation under Friedmann’s guidance.

“I’ve felt a strong bond with UCLA Urban Planning because of this connection,” Mukhija said. “John’s ideas on social justice and planning have influenced me deeply and will continue to play a very important role in the training and education of planners at UCLA and around the globe.”

Friedmann also was the first distinguished lecturer of the Institute of Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin. In May of 2016, Friedmann delivered a lecture titled, “The Ruse of Reason: Poverty and Personal Freedoms in the People’s Republic of China 1950-2015.”

In his biographical chapter in the recently published book, “Encounters in Planning Thought: 16 Autobiographical Essays from Thinkers in Spatial Planning” (Routledge, 2017), Friedmann writes, “I confess a weakness for Chinese philosophy.” The author of “China’s Urban Transition” (University of Minnesota Press, 2005) explained: “I believe this metaphysics has a great deal of explanatory power … I believe it to be useful also in the Western world where we are more accustomed to think in terms of either/or rather than both/and. It is particularly applicable in planning conflicts.”

At the May 2016 talk, Ananya Roy, director of the Institute on Inequality and Demoracy and professor of urban planning and social welfare at Luskin, introduced the prolific author as a “legend in urban planning.”

“For those of us who were trained at other urban planning programs, we were raised on the writings of John Friedmann,” Roy said. “His scholarship, for example, the analysis of world formation, remains foundational to the ways in which we think about cities and metropolitan regions around the world.”

Before the talk, Friedmann sat for a video interview and was asked about the evolution of urban planning at UCLA.

“The vision that I had was that planning was not just a profession,” he said. “We had to begin to theorize about planning, to start thinking, what is planning? What should we expect from this social science-based profession that isn’t simply urban design or land use planning, but goes far beyond that.”

When asked about the connection between planning theory and social justice, Friedmann said, “It’s all value-based, so we have to think very carefully about what sort of values we want to further in the world around us and the world in which we interact. The oldest one is social justice and the whole question of equality and inequality and how to have a more egalitarian society that is inclusive of all different modes of living.”

During his decades-long career, which includes Honorary Professor at the School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia, Friedmann authored more than a dozen books, co-edited nearly a dozen more and wrote almost 200 other scholarly works, including articles and book chapters.

As one of the most highly cited researchers in the planning field — his citations number more than 50,000 — he is best known for his work on regional development planning, world city hypothesis, empowerment in planning and planning theory. His most recent book, “Insurgencies: Essays in Planning Theory” (Routledge, 2011), is a collection of his most influential writing over nearly four decades and is summarized as “Covering transactive planning, radical planning, the concept of “the good city,” civil society, rethinking poverty, and the diversity of planning cultures.”

Awards for his scholarship include the prestigious Distinguished Planning Educator Award from the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning (ACSP) and the same organization established the John Friedmann Book award in his honor in 2013. In 2006 he received the first UN-HABITAT Lecture Award organized through the Global Research Network on Human Settlements, and, is Honorary Foreign Advisor of the Chinese Academy of Urban Planning and Design. In 2008 he was the Harvey S. Perloff Visiting Professor in the UCLA Department of Urban Planning.

He also received honorary doctorates from the Catholic University of Chile, the University of Dortmund in Germany and York University, Ontario.

His personal interests, which included painting, music and poetry, “never flagged, as he saw these as essential to cultivating a sensibility of how things work together to create a whole out of the sum of parts, among which were statistics, economics, politics and history,” Storper said of his colleague.

Friedmann is survived by his wife of many years, Leonie Sandercock, who is a professor at the School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia; his daughter, Manuela Friedmann; and his brother, Martin Friedmann and family.

Full Statements and Tributes from his Colleagues and Friends

Friedmann’s influence and legacy also lives on through generations of scholars and students at UCLA a number of whom commented on his life, legacy and impact, not only on urban planning but on their person and professional lives.

Martin Wachs, distinguished professor emeritus of urban planning

“While many people contributed to the evolution of Urban Planning at UCLA John Friedmann is universally recognized as THE father of the department. Brought to UCLA by Dean Harvey Perloff in 1969, John served as Department Chair during the department’s most formative years and shaped it intellectually in many ways. He was a person of unbounded energy and unlimited curiosity.

“In the most important telephone call of my career, John invited me to consider moving to UCLA and when I did he was my mentor during my early years here. I was a civil engineer interested in transportation and he was a planning theorist interested in regions. He created opportunities for me to broaden my perspective while staying focused on my interests. Busy teaching, writing, and traveling, he always had time for leisurely but substantive conversations about planning and about pedagogy. Our department was his extended family and those who new and worked with him all feel that we have lost a close relative.”

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, professor of urban planning, associate dean of the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, and associate provost, Academic Planning, UCLA

“I consider John Friedmann as the father of our Urban Planning department, a huge figure whose vision has guided our department’s structure, overall mission, and social justice goals. [It’s been] twenty-one years after John “retired” from UCLA at the age of 70, and we are still holding our quarterly departmental Assemblies, our curriculum and admissions committees where faculty, staff, and students meet to decide all major departmental decisions — all legacies of John’s participatory planning process.

“John has not only shaped urban planning here at UCLA but has in many ways transformed and elevated the field nationally and internationally. His concepts, hypotheses and writings about the ‘global city,’ ‘planning in the public domain’ and ‘radical planning’ propelled the rather obscure field of urban planning forward and have been tremendously influential in the social sciences.

“But aside from being a brilliant scholar, John was an amazing human being. I know that I am not the only one who has benefited tremendously from his kindness, mentorship and generosity of spirit.

“John lives in our thoughts and minds. John is UCLA Urban Planning.”

Stephen Commins, lecturer in urban planning

“John was unique. He was my chair, exceptionally rigorous, fair and humorous all wrapped together. He pushed, prodded, provoked and challenged, and also supported me. John was the engine that built up the department when he was chair. He put in incredible hours as a chair, as an instructor, as a chair and mentor, and yet also managed to find time to produce a range of publications. When students would quote something from his earlier work, he might say that was his Marxist, or Buddhist, or Anarchist phase … that jest was really about John being heterodox, not willing to accept simplistic ‘left/right’ or ‘top/bottom’ dichotomies in planning theory or in how we were to explore the world. I treasured that.

“When I was Director for Policy and Planning at World Vision International (1990-96) after finishing my Ph.D., our Latin America VP was a Brazilian who was immersed in liberation theology (before John Paul II killed so much of it). Manfred wanted to meet John, as he was thrilled by John’s book on Empowerment. We arranged a meeting at the Faculty Center, which started off a bit stiff/formal until John started chatting in Portuguese (I couldn’t follow, of course), and that opening up with Manfred’s home language burst open the conversation, which then ranged across languages and ideas and themes for the next 90 minutes. Similarly, when I was managing programs dealing with the civil war in Bosnia, John and I had lunch — we had never discussed the emerging complexities of civil wars in Central America, let alone in the Balkans, but his insights into how political entrepreneurs used ‘culture’ for power were ones that I still use.”

Michael Storper, distinguished professor of regional and international development, UCLA Department of Urban Planning

Let me make sure that you understand the lineage of John Friedmann and his importance to the field of regional planning. The forerunner of our school, the Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning, was created under the auspices of its first dean, Harvey Perloff. Perloff was an economist who had worked under the famous “brain trust” of President Franklin Roosevelt, in the depths of the Great Depression. Roosevelt brought in a number of people from the University of Chicago, among whom were Perloff and Rexford Tugwell. Perloff was instrumental in creating the country’s most important policy in the area of regional development, the regional planning authorities such as the Tennessee Valley Authority. Friedmann was an acolyte of Perloff, so that Perloff brought John to UCLA shortly after he was invited to be founding dean of the GSAUP. Together, they brought in a number of “big thinkers” to be the core faculty of the emerging urban planning department, including Ed Soja, Dolores Hayden and Peter Marris.

Friedmann has to be understood in that context. He was part of the great mid-century bulge of Europeans and European-style thinkers who came into American universities in the wake of depression and war in Europe. With his Austrian roots, John combined a European style intellectualism and broad culture, with American pragmatism. Like all of those of his generation of Austrians, he was traumatized by what had happened in Europe and saw policy as a way to make the world better in order to avoid such outcomes. Chicago was a crucible of this mixing of pragmatism and European big theory and humanist culture. John was trained in regional economics, but was deeply cultured in classical music, poetry and continental philosophy.

Perloff and Friedmann, along with Bill Alonso of Harvard, published the early fundamental texts and edited books in the emerging field of regional planning. John was close to Walter Isard, who established the Regional Science Association and its associated journals (still important to the field), as well as having contacts with all the European big names who were working to rebuild Europe through its regions, as the U.S. was doing so in order to get out of the depression and then to spread the wealth after the war.

It was also the period of 20th century “economic development” theory and practice, meaning the rise of a field of academia and practice devoted to combating under-development, in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. Friedmann worked with Nobel Prize winners such as Gunnar Myrdal, and the renowned economist Albert Hirschmann. Friedmann spent many years in South America working on growth pole policies. So he brought a real global outlook and sensibility to UCLA.

The culture of our department was like a global intellectual salon at the time, with big ideas and world class intellectual speakers coming through for the Thursday Evening Lectures that John was instrumental in designing into the department’s life.

Later, as he moved away from nuts-and-bolts regional planning, John’s background and culture in continental European philosophy infused his work. With a line of inspiration that went from Aristotle through Kant to Habermas and Bergson, he was interested in experience, in the life-space, which he contrasted to economic space, how planning interacted with notions of a good and creative and fulfilling way to live. His later work explored power, identity, domination, and experience, with these philosophical traditions brought to bear on these questions. He was always reluctant to endorse typically American technocratic approaches to urban problems, eschewing the narrowness of the American academy, all the while hewing to his pragmatist side. His interest in painting, music, and poetry never flagged, as he saw these as essential to cultivating a sensibility of how things work together to create a whole out of the sum of parts, among which were statistics, economics, politics, and history.

On John Friedmann and the Implications of Regional Planning

By Susanna Hecht, professor of urban planning

In his later years John Friedmann was largely concerned with social movements as political processes as underpinnings to planning. This focus overlooks his earlier emphases in planning in understanding large scale river basin planning — the TVA, “from scratch” city construction, such as Ciudad Guyana in Venezuela, and his role in Latin American development politics, all of which were at earlier phases in his career but which informed his later ideas about transactive planning, and his general discomfort with bureaucratic planning as processes. Like most planners, he struggled with the idea and theory of planning, in many ways deriving his later ideas from Habermas, but also I would argue, to some degree from the failures of the transfer of planning models that actually seemed quite successful and, indeed, were practically text book cases of large scale river basin and territorial planning like the TVA — the Tennessee Valley Authority.

It is important to situate his early career in the intellectual ambience of the University of Chicago which had an outsized role in the intellectual underpinnings of the New Deal and post dust bowl recovery of the regions of Appalachia affected by the TVA. As a protégé of Harvey Perloff, he was exposed to the extraordinary influence that Chicago was to have on urban theory, especially through the idea of urban ecology ( not in the sense we use this term now as a socio-biotic domain) but rather as analogue to biotic systems with urban dynamics of succession ecological complexity and growth echoing as metaphor and reality the theories emerging from Chicago’s powerful biology department which was foundational in the development of ecological and succession theory.

Chicago biologists were deployed to help in landscape recovery of the degraded dust bowl lands (what we now call recuperation ecology), and for large scale land use planning in the Tennessee River basin. (The TVA embraces Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, parts of Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia) This ecological interest was complemented by the intense concern of new dealers like Tugwell and Henry Wallace to improve rural and urban conditions in the most desperately impoverished areas of the south through flood control, electricity generation, rural electrification agrarian change, regional industrialization and urbanization in the context of comprehensive land use regional planning which included natural resource management and social investments in health, education and infrastructure.

It was the largest such exercise in the U.S., it served as a model for basin development throughout the U.S., especially in post dust bowl Midwest and developing Western states, and it became paradigmatic for developing countries as well. Founded in natural resource management, structural transformation and urbanization and industrialization, the TVA experience was also seen as a template for tropical development. As a technocratic exercise it was often lambasted as a socialist project (or Soviet-style planning) and from the left as an anti-democratic outcome of high handed experts. It did work, however, in a textbook manner, in transforming hard-scrabble, impoverished agriculture into modern forms, stimulating rural to urban migration and enhancing industrial development and other forms of energy-based development, and raising income health and education levels from truly those of third world countries to levels more in line with other areas in the U.S. While this model of comprehensive planning seemed to follow the recipe laid out by development economists and New Deal planners, and the kind of idea of linear progress, John Friedmann’s experience in Latin American in many ways changed that and his views of planning.

The Early 1960s witnessed the idea of moving the ballast of national economies into their interiors in Latin America. Rather than remaining in colonial capitals perched on coastlines, the idea was to situate important administrative and industrial cities in the interior of their countries. Building Brasilia, and enhancing Manaus and Belo Horizonte were archetypical in their ways, as was the development of Ciudad Guyana in Venezuela. All these cities developed fuller expression under authoritarian regimes, and in addition to urban development, embarked on massive infrastructure (dams for electricity) and industrial investments. Ciudad Guyana was developed on a famous waterfall to capture the energy to enhance industrial steel and manganese development. It became an important migration zone, but what then happened is rather than following the TVA model into a glorious future, it descended into what John Friedmann would call, the Citadel and the Ghetto: the world’s city style of massive poverty and informality, coupled with an international style modern urbanism with a high-wage managerial but also oligarchic class structure. In Ciudad Guyana this took the form of 1950 style suburban development coupled to the favela housing and livelihoods. These lives contrasted mightily with the planners imaginary and this clash of outcomes and its inequalities were movingly described by his friend and co researcher anthropologist, Lisa Peattie.

This experience would also thrust him into the Core and Periphery forms of planning and urbanism associated with the theories of underdevelopment and dependency that were so prominent in the intellectual architecture of the 1960s and 1970s. What was clear was that planning modalities in repressive environments and high levels of oligarchy and inequality were merely reproducing themselves within a new urban framing driven by “center” patterns of accumulation at the national, and international levels. After all US Steel was the main industrial beneficiary, and those suburban houses, fancy apartment towers were for its local and international managers, not for the more blue collar staff. In this sense the transformation of the region which was at the rhetorical level infused with ideas and ideologies of progress, had far more uneven outcomes and was not like the regional process which, for all its faults had been the development outcome of the TVA.

This failure of planning and planning theory pushed Friedmann into a much more complex set of analyses, where in fact he viewed the “expert systems” as lacking broader knowledge of societies and knowledge of and about local populations’ needs and desires even as they would be affected by plans and planners. His transactive planning and social learning models emphasized an approach the leaned on knowledge sharing as a more collective process and later on, insurgent and political action as increasingly key to transformation, especially as planning became more professionalized, bureaucratic and in many ways, complicit in structuring inequalities. While it has to be said, his framings were rather derivative from other stronger intellectual trends, his stylish prose, clarity of thought, and sociological training brought a more European sensibility to planning which while slowly changing, had been a kind of “tyranny of experts” — a legacy of new deal planners. As those planners moved from the rural to address more urban questions, and saw urban blight in many ways as part of the natural history of cities, he certainly felt that all the knowledge of places did not inhere in local planning departments. He was always attentive to the big picture of what shaped places, and to his credit, always saw rural and resources as a central part of understanding planning dynamics, and especially the dynamics of urbanization and especially in the third world.

As the profession moved away from the “rurality,” resource and urban connectivities, it ceded this arena to natural resource managers, and only very recently have these connections come back into planning focus, although very belatedly. Friedmann in this way was prescient but also very broadly experienced in national and international regional planning that deeply included rural livelihoods and transformations, and that in many ways these urban areas could not be understood without resource hinterlands. It is this world view that explains why I am in Urban Planning.

At another level, he loved Latin American literature and especially its poets and musicians. He liked to translate Pablo Neruda, the great Chilean poet, as well as the Spanish poet Frederico Lorca, and was an avid reader of Borges (who actually has plenty to say about planning), and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He kept interesting diaries, for example about his early travels to Manaus, and the Amazon in the chaotic interregnum of weak democracies before the iron handed authoritarians came to power. His Latin American experience was so colored by the authoritarian period, and so inspired by its artistic resistance that his later insistence on civil participation and insurgencies really come as no surprise.

It seems like a distant time, now, almost impossible to imagine given current intellectual cultures, but he would have gatherings where young faculty would meet with him, and read out favorite poems. I usually read Ann Sexton — a bohemian feminist poet. But he was a Neruda and Lorca guy, reading the poets who wrote under the authoritarian (Spanish and Chilean) moons.